Thinking about Nazrul in Cuba: Love and Revolution

1

I visited Havana, Cuba, in January this year. I was invited there to give a lecture on the significance of Fidel Castro and the reception of the Cuban Revolution in Asia, Africa, and Latin America at a symposium organized by US-based Global Center for Advanced Studies in collaboration with the University of Havana. I also interacted with some Cuban poets, writers, artists, and activists. And whenever I could, I talked to the people in Havana's streets. It is they who taught me the most about Cuba, Castro, and Che. They even made me think about our own poet—and my all-time favorite poet—Kazi Nazrul Islam (1898—1976), undoubtedly one of the major figures in Bengali poetry and music.

In fact, I brought up Nazrul frequently in my conversations with the folks I met in Havana. Nazrul also figured prominently in my lecture on the Cuban Revolution. But why Nazrul in Cuba?

The first Cuban I met in Havana was Raul, a taxi driver, who told me: "Cuba is no paradise, and we still need to address many problems here. But, as socialist, we're strong, and we know how to struggle and fight—fight against US imperialism." And in Nazrul's voice we continue to hear the cadences, inflections, and accents of struggle, resistance, and liberation. And it is Nazrul—organically rooted in the struggles of his own people, i.e., poor peasants and workers—who could inspire the Cuban writer David Fernández Cherican to offer such lines as "Se solicita un mundo/ Sin monopolios/ Ni policia" (Wanted: a world/ without monopolies/ without police). When I discussed Nazrul with some of my comrades in Havana, while also sharing with them a few of Nazrul's major poems, they responded by saying: "Nazrul is our poet—a Cuban poet as well."

I myself saw some immediate intersections between Nazrul and a particular constellation of Cuban poets constituted by figures like Nicolás Guillén (1902—1989), Pablo Armando Fernández (1930—), Roberto Fernández Retamar (1930—), Miguel Barnet (1940—), and Nancy Morejon (1944—). Their different styles and contexts and conjunctures notwithstanding, they all mediated and mobilized in their works the Marxian idea of the "Permanent Revolution." Nazrul goes almost literal about it in "Bidrohi," declaring at the top of his voice: ": "I, the great rebel,/ shall rest in quiet only when I find /The sky and the air free of the groans of the wretched of the earth." I thought to myself: Had Che Guevara known Nazrul's high-voltage political poem "Bidrohi"— stylistically and aesthetically innovative as it is—he would have always kept it as an explosive in his pocket, where he used to keep his favorite Neruda poems.

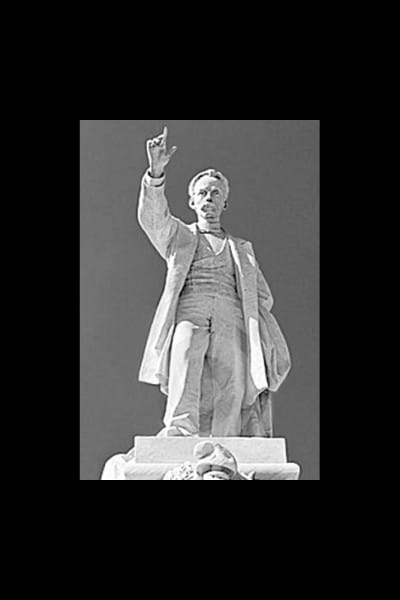

Then there is José Martí (1853-1895)—Cuba's national hero, universally known as the "Apostle of Independence." He is also one of Latin America's most influential poets. Che Guevara himself drew inspiration and energy from Marti, viewing him as the quintessential revolutionary. As José Kozer once put it, "Every Cuban in his heart of hearts wants to be José Martí." When I stood in front of the sunlit towering monument to Martí—the 59-foot-tall monument that looms over the famous 11-acre "Revolution Plaza" in Havana—I immediately thought of Nazrul and his lines: "Say, Hero / Say: My head is eternally held high."

And I found it compelling to compare Nazrul to Martí in Havana. Both admired Walt Whitman. While Martí introduced Whitman and his free verse to Spanish-language poetry, Nazrul for the first time creatively appropriated in Bengali poetry the Whitmanesque spirit itself. One finds a number of parallels between Whitman's "Song of Myself" and Nazrul's "Bidrohi." One can also trace even more thematic and stylistic parallels between Whitman and Martí. But I find Nazrul much more passionate, more combative, and even more radical than both Whitman and Martí. While I think Whitman's "I" cannot range beyond the horizon of a certain kind of democracy, and while Marti's "I" is decisively in the middle of life-and-death struggles for national independence, I think Nazrul's "I"—used more than a hundred times in "Bidrohi"—exemplarily inaugurates a collective revolutionary subjectivity—an unprecedented event in the history of Bengali poetry.

2

So, while in Havana, I realized once again that Nazrul is more than a rebel poet. He is in fact a "revolutionary." As Nazrul himself repeatedly declares at different registers in his poem "Dhumketu" [The Comet]: "Again I've come for the great Revolution." Nazrul is also a revolutionary in the hard political sense of the term. Along with his comrade Mujaffar Ahmed, Nazrul contemplated building a real revolutionary communist party in India in 1921—the year in which he wrote his "Bidrohi." Then, in 1925, he actually ended up founding the "Labor Swaraj Party." Nazrul himself wrote and signed its manifesto that clearly bespeaks his profound predilection for revolutionary party politics in colonial India.

Further, the pages of the Dhumketu—the magazine Nazrul edited in 1922—amply demonstrate Nazrul's deep-seated aversion to piecemeal reform under the British Raj and his profound faith in the question of revolution. There are other examples of course. But, true, it was Nazrul who—before Gandhi or even any of his contemporaries—issued a call-to-action for nothing short of the total independence of India from British colonial rule. But Nazrul—well before the Caribbean revolutionary Frantz Fanon—realized that national liberation is undoubtedly necessary and yet profoundly inadequate.

What, then, is more important for Nazrul was a total rupture with the existing order of things—a revolutionary transformation of society at large. In fact, Nazrul is interested in nothing short of the total emancipation of humanity. And, for Nazrul, the Revolution is love made visible-- the love of the oppressed Che Guevara once asserted: "[…] the true revolutionary is always guided by a feeling of love." Nazrul is certainly a true revolutionary in this sense. For Nazrul, love itself is revolutionary.

The points made above are all evident enough in at least two collections of Nazrul's poems, titled Sammyabadi [The Communist] and Sarbohara [The Proletariat], published in the nineteen twenties. Given the revolutionary humanism exemplified in these works, I think Nazrul can also be reckoned a true predecessor to such major "third-world" revolutionaries as Aimé Césaire, Amilcar Cabral, Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, and Fanon himself. It is this very revolutionary Nazrul that preoccupied me in Cuba. And it is this Nazrul that remains relatively unheeded in contemporary Bengali literary criticism.

To honor the legacy of Nazrul then is to rethink, among other things, his revolutionary poetry and politics at a time of monstrous inequalities, injustice and alienation, against which Nazrul had fought with such courage, conviction and commitment. And love. And struggle is love made visible.

Azfar Hussain teaches Liberal Studies/Interdisciplinary Studies at Grand Valley State University, USA and is Vice-President of the Global Center for Advanced Studies (GCAS).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments