The hidden side of natural disasters

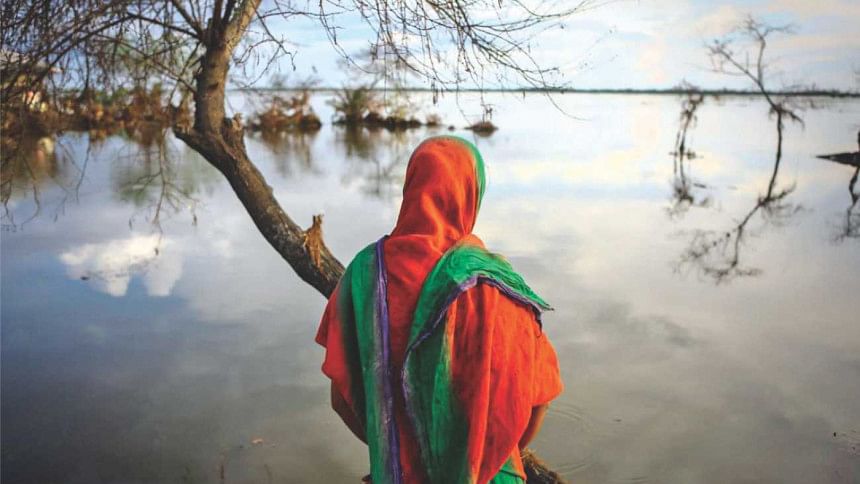

“I was trapped inside a house for 15 days. The (flood) water was rising every day and I was taken to an unknown place and tied up. Those men were human, they wore clothes like any normal person, they were thrice my age and had children at home. I was raped uncountable times every day. I heard them planning to sell me because the water was going down. They were fixing my price and someone said any price was okay.”

— Honufa (picture above)

A 2007 study conducted by the London School of Economics in 141 countries over the period of 1981 and 2002, found that natural disasters and their subsequent impact, on average, kill more women than men. In 1991, for example, of the 140,000 people who died in Bangladesh during Cyclone Gorki, 90 percent were women.

Today women are no longer swept away in the floodwater by the thousands, and Bangladesh is a role model for climate change adaptation, and yet, three decades later, Bangladesh ranks sixth out of seven countries in South Asia Women's Resilience Index, a report by The Economist Intelligence Unit that examines the role of women in preparing for and recovering from disasters. And last year in November, in the wake of Cyclone Roanu, the Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Cluster, co-chaired by the Ministry of Women's and Children's Affairs (MoWCA) and UNFPA, was established to enable effective responses to violence against women and girls during emergencies.

Unfortunately, there is very little documented work on gender-based violence in the aftermath of natural disasters. Arshad Muhammad, Assistant Country Director of CARE Bangladesh, says, “There is no clear study/analysis of what specific GBV concerns or incidents happen in Bangladesh in small or medium scale disasters according to location/region and type of hazard.” According to him, as there is always a scarcity of resource, food, cash, shelter, and wash are given priority. Gender violence and gender considerations are mostly considered as a cross-cutting subject and do not get the attention or, consequently, the funding they require. After Roanu, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) estimated that a minimum of $1.2 million was needed to ensure reproductive health needs and protect the rights of women. While gender budgeting and inclusivity are a priority for the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief, preventing violence against women is one of the most underfunded efforts in humanitarian crises.

Sabina Parvin, Project Manager at PLAN International, echoes this concern: “In government documents on disaster management, children and women are denoted as priority groups, but during emergency response, their protections issues are not given special attention. MoWCA and the Ministry of Social Welfare are responsible for women and children, but there is limited intervention of these ministries at the national and field level.” Shockingly, these ministries have no emergency response plans for protection of women and children during disasters. As a result, during emergency periods, neglect, exploitation, impoverished conditions and separation from families ultimately culminate in sex trafficking, early marriage, and children being sold into labour.

Children at risk of early marriage

Bangladesh has the highest rate of child marriage of girls under the age of 15, and this is only exacerbated during disasters. According to Sabina, this is a very common phenomenon in flood and river erosion affected areas in particular, as it is perceived as a means of protection from rape and abuse and for reducing the cost of providing food and shelter for large families. With similar hopes, millions of parents marry off girl children before their 15th birthday. In 2016, 6.2 million girls under the age of 15 were already married in Bangladesh.

Child marriages spiked following cyclone Sidr in 2007. Fatima, a mother of five in the coastal district of Laxmipur, says, “I don't have enough money to feed my daughters – that's how I decide when I should marry them off.” She thinks it is the only way for her daughters to have a decent life. Even after their house and land were swept away by river erosion, Fatima's family did not receive government assistance, while others did. “They bribe the government officials – they give 2,000 taka and then they continue to get relief… but we can't give anything so we don't get anything.”

There are no officials at the local level responsible for child protection in normal situations, let alone emergencies. Rather, local government officials routinely fail girls who are most at risk. “When the kazi saw that my daughter's birth certificate said that she was 14, he refused to do the marriage,” says Farhana Begum, whose family's crops were destroyed nearly every year in the past decade in Sirajganj. “He took it to the [local government] chairman and got it changed and then performed the marriage.” The chairman charged the family 100 taka to change the birth certificate.

This dangerous traditional practice is the veil behind which violence against girls is perpetuated and is itself a form of violence. “Sexual violence is inherent within child marriage as it is still sex with a child under minimum age, regardless of whether it takes place within the context of marriage,” explains Yeva Avakyan, senior advisor for Gender at World Vision US.

Laki, 16, also from Sirajganj, where hundreds were left homeless due to river erosion even this year, was married when was 12 and her husband was 27. The abuse began immediately after the marriage, she says, first at the hands of her parents-in-law, but then from her husband too, culminating in him kicking her in the stomach when she was five months pregnant. According to Avakyan, girls who are married early are denied their right to education, are isolated from family and friends, and are more likely to experience domestic violence and serious negative health outcomes as a result of early sexual activity and, in many cases, early childbirth. Married girls experience much higher rates of maternal morbidity and mortality, and are more likely to have children with low birth weight, inadequate nutrition, and anaemia.

Overcrowded shelters breed insecurity

Last year, half a million were forced to flee their homes during Roanu. This year, 475,669 in the coastal districts had to be evacuated. “Displacement sites, camps and centres are usually overcrowded and, in such situations, women usually do not have enough space for privacy, bathing, breastfeeding or menstrual hygiene. The conditions of the washing areas and latrines, for example, the absence of lighting, internal locks and adequate segregated space for women and men is often inadequate for women and girls' privacy and safety,” says Arshad.

In all emergency situations, and most particularly in situations of displacement, normal community life and its inherent protection mechanisms are disrupted. While people are already returning to their homes, in Cox's Bazar, for instance, trees have been uprooted and shanties destroyed. At least 20,000 houses have been damaged and the trees now litter the countryside, blocking roads all over the district and preventing access to parts of Cox's Bazar. In such circumstances, where communication is cut off or made difficult, collecting relief itself becomes a trial. Poorly located and managed distribution points for relief items often become sites for sexual harassment, exploitation and abuse.

Of the 1.3 million people affected in Roanu, 3.5 lakh were women and girls of reproductive age, and around 30,000 pregnant or lactating mothers. In a 2014 survey on women in natural disasters in the southern coastal region of Bangladesh, it was found that 60 percent of women who stayed in cyclone shelters responded that they were harassed, molested, taken advantage of, and ogled. While new provisions for women and girls include special cash grants for pregnant and lactating mothers, clean delivery kits, and “dignity kits” (burkas, personal hygiene supplies, a flashlight, and a whistle), there is room for improvement in gender based violence prevention and child protection. While UNFPA is now seeking $1.5 million to scale up emergency reproductive health services and safety for women and new-borns, and UNICEF is ramping up efforts to provide children devastated by the storms with life-saving services and support, violence against women and children has once again been sidelined as a cross-cutting issue.

This year, in the hardest hit district of Cox's Bazar, 72,000 women and girls of reproductive age have been directly affected. An estimated 19,400 are at an increased risk of experiencing violence within the next 12 months in Cox's Bazar alone. This insecurity is reflected in the needs assessment of Roanu affected areas which found that even the cyclone shelters were inadequate to accommodate all affected people's needs, and thus women and girls in particular did not feel safe and secure to come and stay at these places. As one woman from Shamlapur, Cox's Bazar says, “The clothes I am wearing have been wet for days and the rest are soaked with mud. It is not easy to collect food from the relief agency like this. The bathroom is damaged so I had to wait until dark to use it to not be seen.”

Refugees at even greater risk

The culture of violence can be one of the greatest challenges for people like refugees who are affected by crisis. In the two Rohingya camps in Cox's Bazar – Kutupalong and Nayapara – 70 percent of the houses have been damaged or destroyed, including community and health centres, birth clinics, schools, dormitories for female police officers, warehouses, and offices of the camp administration and of non-government aid organisations. Electricity has been cut off and is not expected to be back for days. According to a report on the camps by UN Women (UNW), about 80 percent of the residents are women and children who already lived under challenging conditions with unmet basic needs and protection concerns before the cyclone.

Breakdown in law and order can mean that perpetrators of sexual violence often abuse with impunity. Marie Sophie Sandberg Pettersson, Project Analyst at UNW, says, “The women have reported not feeling safe staying in the temporary emergency tents or going to the toilet at night.” While UNW and UNHCR are providing plastic sheets, ropes and other items to people in the two camps for emergency shelter and are planning to distribute solar lamps for temporary lighting and electricity supply, these are only temporary solutions.

The first step is to acknowledge the problem

Sabina says, “While MoWCA is taking initiatives to address women and children's issues, their activities focus on the livelihoods of women affected by disaster, not for the protection of children and women per se.” She believes there is a lack of awareness of the need for protection. “Consequences become visible only after some time has elapsed, and by then, the needs of the community have changed and protection issues are not a priority.” To protect children from early marriage, the government and NGOs need to take long term initiatives by integrating child protection into response plans, and communities need to identify alternative livelihood options to mitigate the risk of disaster. Insurance can be introduced to reduce the loss and damage after disaster, thereby helping to prevent drop-out from schools and child marriage, she adds.

Arshad, on the other hand, suggests community watch groups, functioning complaint systems, and female frontline relief workers. Groups formed from women and adolescent girls keep watch, especially when there is displacement to shelter or make-shift arrangements. In remote areas, he adds, clinical management of rape cases is particularly important as referral arrangements for medical and psychosocial services may be inaccessible or even unheard of. Of course, preparedness for this has to be done in non-emergency times.

The response mechanism primarily fails as a violence-free life is not acknowledged as a primary need for survival. While emergency responses focus on ensuring access to services and commodities required for survival, they do not look into the loss of control over these necessities due to exploitation and abuse. There is a saying: 'disasters do not discriminate; society does'. No amount of planning, preparation, or scientific investigation can avert catastrophe, but preventing social catastrophes most definitely lies within our collective human capacity.

Comments