DRAINAGE deplorable

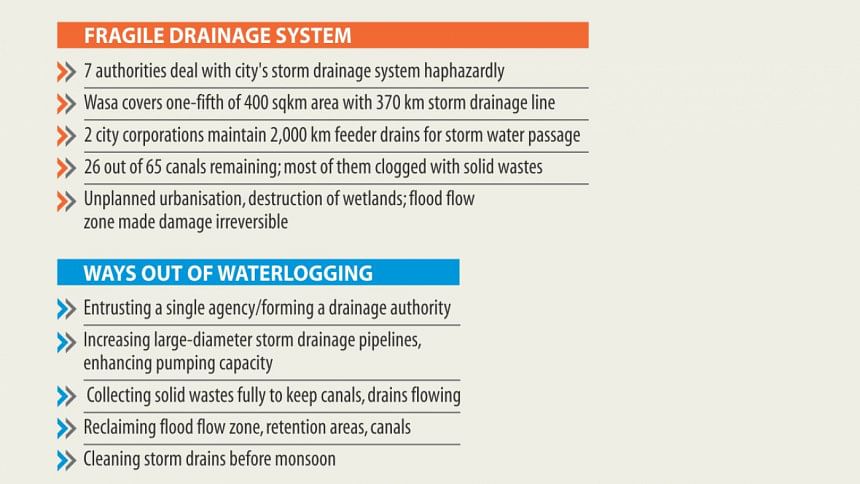

Inadequate storm-water drainage system managed by seven different authorities with little coordination among themselves is the reason why Dhaka streets suffer deluge every time there is moderate rain.

The authorities do their job haphazardly. They hardly know what the others are doing, say officials concerned.

In a well-managed network of storm drainage system, rainwater instantly runs into the low-lying retention areas. But, it takes hours for rainwater runoff if the network is faulty or destroyed, leading to immense public sufferings.

The worst-affected areas in the capital include Shantinagar, Khilgaon, Bashabo, Malibagh, Shantibagh, Rajarbagh, Mugda, Mohammadpur, Badda and different parts of Old Dhaka, say the officials and urban planners.

Each of the seven authorities “looks after the network under its jurisdiction” and none of them is assigned to do the job single-handedly, said Taqsem A Khan, managing director of Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (Wasa).

The six other authorities are the two city corporations, Water Development Board, Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha (Rajuk), Cantonment Board and large private housing developers like Bashundhara, he said.

“Dhaka Wasa with 370km storm drainage pipelines covers only one-fifth its service area of 400sqkm.”

The two city corporations maintain over 2,000km of feeder drains (open and small diameter pipes) to carry rainwater, and liquid waste from homes into canals and wider diameter storm sewer system, according to Sirajul Islam, chief town planner of Dhaka South City Corporation.

While Bashundhara residential area's storm drainage is managed by the private developer itself, three organisations -- Rajuk, Wasa and the city corporation -- have developed the drainage facility in Uttara Model Town area.

The storm-water drainage management of the Dhaka-Narayanganj-Demra (DND) and the cantonment areas are being looked after by the Bangladesh Water Development Board and the Cantonment Board respectively.

Khilkhet has no formal drainage facility. It is mainly dependent on the local canals and other water bodies for rainwater runoff.

However, two canals -- each at least 100 feet wide -- have to be dug along the 300-foot road there as many of the water bodies had already been filled up, Wasa MD Taqsem said.

Wasa covers some 400 square kilometres area of the capital. But some 350skms of the surface is paved, preventing the ground from soaking up rainwater, he said.

He also said rainwater would have gone under the ground naturally, instead of flooding the city streets, had 50 percent of the surface been open earth.

Again, the rainwater could easily flow into the canals and ponds if they had not been filled up.

The city's natural drainage system -- comprised of a network of 65 canals and four rivers, numerous water retention areas (ponds, ditches), extensive low-lying areas and flood flow zones --- is consistently being destroyed in the name of development.

The low-lying wetlands and flood flow zones earmarked in the DAP (detailed area plan) no longer exist as those were filled up, in many cases with official approval, according to officials concerned.

With its current capacity, Wasa's system can drain 45 cubic metres of water per second from the capital. But, it cannot do that as ways for rainwater receding are obstructed, says the Wasa MD.

According to officials concerned, rainfall above 40mm in Dhaka would take at least three hours to recede, as the available pumping facility is capable of draining only 20mm of rainfall.

Wasa says that most of the 26 canals that still exist are clogged with solid waste.

Ten kilometres of canals have been turned into concrete box culverts to build roads over them, reducing their capacity to absorb rainwater.

Taqsem said the embankments cordoning off the Dhaka city -- meant for flood management -- have also become “counterproductive” for the urban storm water disposal and that it required artificial pumping at the cost of public money.

So, setting adequate storm drainage pipes and enhancing the pumping capacity could be a way out, he said.

Surrounded by four rivers, Dhaka was supposed to remain a delta with extensive wetlands all around, show planning documents like Flood Action Plan and the DAP.

According to the plans, the city should have conserved 5,523 acres of water retention area, 20,093 acres of canals and rivers and 74,598 acres of flood flow zones.

Only 20 percent of the total sewage is taken to the Pagla Treatment Plant through sewer lines and most of the rest is just released into the storm drains, posing serious threat to public health.

The Wasa MD also said five more plants would be built by 2025 so that all human wastes from the city were treated.

DESTRUCTION OF WETLANDS, PONDS

Urban planners time and again warned of grim consequences if the flood plains and the wetlands continue to be destroyed for “mindless commercial gains”.

However, nobody seems to be paying any heed to the warning. The real estate developers are being allowed to indiscriminately fill up canals, ponds and other water bodies in and around the city, they said.

On the other hand, natural low-lying wetlands, flood flow zones, storm water retention ponds, ditches and canals have all been ravaged and filled up blocking the natural passage of rain.

Canals, rivers and water retention areas collect, carry and retain rainwater and are connected to each other as a drainage network. But in recent decades, the city canals have been grabbed.

Open space and water bodies help evaporate a third of the rainwater, percolate another third while leaving the rest to run down to retention areas.

Since DAP gazette notification in mid-2010, nearly all of the conservable wetlands have been filled up -- some with silent approbation and some with formal government approval, said official sources.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments