Take a bow, break a leg, and stop the show

This year has been my 45th year on stage. So my editor and I thought: Why not have a series of writings that celebrates the creative space I have called my own for so many years?

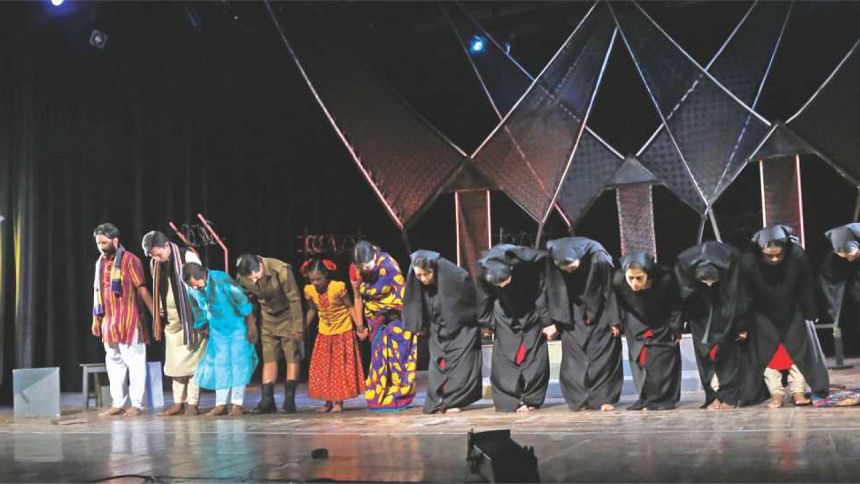

Let me begin with the end. When the play is over, we, the actors who have performed, take a bow which is called the curtain call. In the last three or four days of rehearsal for a new play, we rehearse the curtain call as well. Different plays have different curtain calls. One thing is common though—we invariably take the bow in an expression of our humility.

The stage has borrowed many a practice from the West, and taking a bow is one of them. In the early '70s, Zia Haider, renowned playwright, stage director, and president of our group, taught us the curtsy and the bow. Having studied drama at East West University in Hawaii, he knew more about theater etiquettes than most of us. Women curtsied by holding the two sides of the dress (in our case the sari), and men took a bow by taking off the hats. By the '80s, we gave up the curtsy, and took up the bow, rendering the act unisex.

Before staging a new play, we, the generation that was born under British rule, wish each other by saying "break a leg." I had always wondered who came up with the term and what it really meant. Now I have learned it may have originated from the practice of curtsying or bowing, both of which require you to fold your legs at the knee, thus "break a leg", or "have a great show so that you may break the leg on a happy note at the curtain call."

Some conjecture that "break a leg" could also be meant to ward away evil so that the performance is not jinxed, just like we cross our fingers when we are talking about something that we want to go well. By saying "break a leg," we have nullified the jinx, and the play is safe.

Our presentation has adopted a lot of practices from Western culture—British, European and American. The audience that comes to watch a play is not necessarily familiar with these customs. In Broadway and West End, I have seen the audience continue to applaud until the whole cast comes back to the stage for another bow. The cast usually continues to return to the stage, taking up to six to eight bows, and exiting for good only once the applause has subsided.

We like to call our audience our Laxmi. If the auditorium is full, we are so happy that this in itself elates us and the quality of the performance goes up many notches. But Laxmi has not been taught by Western culture. Our Laxmi does it quietly, and one has to get used to it. Though a loud applause does give the performer a high, one has to feel that elation in other ways, and we should not expect our Laxmi to behave in a Western manner. Sometimes we, the performers, complain like spoilt children, mumbling under our breath, "Bangalis do not know how to clap." My two cents is that we should be more accepting. Before we whine and pine away any further, let us also remind ourselves that the cell phone in almost every person's hand in the audience also makes it harder for the individual to give a big clap! That is the hazard of new age technology, and it merits a separate discourse.

Although the curtain call is perhaps not met with as loud a response as in the West, we have "show stoppers" as marks of appreciation. If a scene is well enacted, at its end, the performers express their approval with a loud applause. But applause at the end of a scene does not really "stop" the show, i.e. interfere with it. You are in trouble when you get laughs or applause right in the middle of a scene. It is usually a loud and a long laugh, accompanied by claps. Sometimes, while the audience is still reeling with laughter, the performers try to go on with the scene, but end up making a mess. In such a scenario, the audience cannot focus and the dialogue has simply gone over their head. The rule is, at a show stopper, the performers should stay on script and in character until the laughter has subsided. After a few viewings of a play, we can predict which moments will be show stoppers, and are prepared for when the laughs will be coming. But there is a catch here as well. The expectation of laughter creates a sense of competition, and every actor tries to outdo the other in wringing out a laugh from the audience.

Exasperated by the melodrama and the overacting, a director of my group had once abandoned a play he had directed for many years. He had said, "I cannot control your overacting; the play is no longer my own. It is yours. Do it whichever way you want." It was the '90s, the play Dewan Gazi, and the director Asaduzzaman Noor MP. Thankfully, things changed when we made a comeback with the play in 2015.

*Much of my writing on show business is and may be inspired by the book Totally Scripted by Josh Chetwynd. This is a book on the history of the idioms in the English language that originate from Hollywood and Broadway.

Sara Zaker is a theatre activist, media personality and Group Managing Director, Asiatic 360.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments