Coleridge: Stories of Betrayal, Pain and Misunderstanding

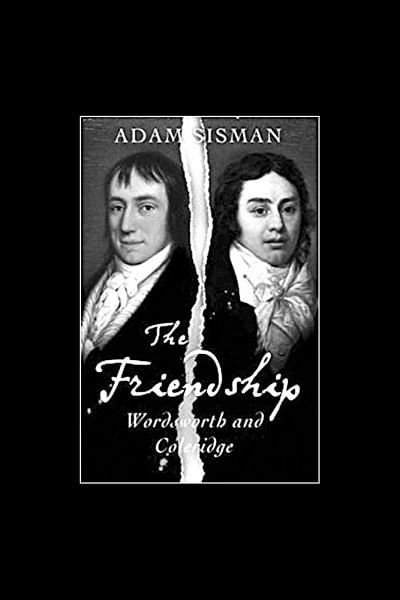

Sometime in 1797 something magical happened in English literature. Two poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge by name, went out for a long walk across the countryside of England, hoping to bring about revolutionary changes in poetry. They had then and later many rounds of deep and animated conversation. They vowed to work together. Their collaborative work became famous as the Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems. These two men were at the vanguard of the English Romantic Movement. Throughout history they have been seen as 'friends.'

As Dorothy Wordsworth (sister of William) recalled, the ardor of excitement that Coleridge brought to this friendship was amazing. Dorothy remembered that on his first meeting with the Wordsworths, Coleridge ran down the road, climbed a field and landed up in their cottage—an act that surprised agreeably the otherwise equable and meditative Wordsworth. What really struck them was that a man with such a waif-like appearance and adenoidal expression (thick lips, noisy breathing) could have eyes that would move and roll, as if, in frenzy, and could win anyone that they came across, with their dreamy far-away expression. Wordsworth, so to speak, fell in love with the man right away.

Love, of course, has always a fairytale dimension to it in the beginning. Everything is so amazing when one is in love; it feels as easy as it is smooth going downhill. Unfortunately, however, people in love soon face critical situations that test the steel of that love. Only in fairytales, as we all know, the ending is always good.

But did the relationship between Wordsworth and Coleridge develop like the ones in fairytales? Quite the opposite, in fact.

When Coleridge died in 1834, Wordsworth was still alive; he still had 16 more years of his life to live. He penned the following lines in eulogizing his late friend: "Nor has the rolling year twice measured, / from sign to sign, its steadfast course, / Since every mortal power of Coleridge / Was frozen at its marvelous source." But these lines are nowhere close to telling us the fact that for the last three decades previously the two friends had lived in estrangement from each other. Indeed, for more than a decade they had even stopped visiting each other. Lyrical Ballads, that brainchild of their friendship, was by this time a monument of a fuzzy past. There were a lot of promises made around this collaborative work and most of them had been delivered; all of them, however, had become irrelevant by this time as far as the friendship was concerned.

Even after the first edition of Lyrical Ballads had come out in 1798, signs of strain in their friendship were evident. In the second edition, Wordsworth refused to include Coleridge's Christabel. He even altered and modified some of Coleridge's poem without informing the poet. Coleridge was deeply hurt. The contrasts in their poetic natures were becoming too obvious to be ignored: Coleridge believed in the creative power of the poet, while Wordsworth subscribed to a kind of Pantheism. That was clearly a recipe for conflict. The friendship soon was on the line.

What did not help the matter was some of the provocative comments Wordsworth made in their circle of common friends. Comments such as Coleridge was too "metaphysical" or too "self-obsessed." He had even gone out of his way in a letter to Montagu to confide that Coleridge was a "drunkard" and a "liability". That was something less than what one expects from a great poet and not quite what one expected from the man who had shown great sympathy for common people and ordinary lives. Coleridge undoubtedly had some problems—his marriage, addiction, and coxcombical adoration of creative people. But they were not the causes of the main problem he was facing; they were rather, as pioneering biographers have pointed out, symptoms of things going fundamentally amiss with his life. But Wordsworth was found wanting in time and interest in understanding them.

Any friend of Coleridge knew that 'precocity' was the right term to define the kind of man that Coleridge was. He knew a lot, read a lot and promised much. He was a "library-cormorant," as he said of himself. It was a privilege to listen to him preaching. His voice "rose like a steam of rich distilled perfumes," Hazlitt once observed. He was a prodigy to men; yet, he was such a sorry sight. His life was a series of incomplete projects; he seemed caught in limbo, and his was a life punctuated by betrayals of people he wanted to latch on to for security.

Things like these happen when you are, as any psychologist will confirm, unsure of what your abilities are. Coleridge certainly had a history of struggle with his poetic Muse. This struggle is of seminal importance in understanding the root of his troubles in life. Throughout his life he kept switching to new things, going to new places, looking for new people to interact with; there was a risk of failure in these ventures but it was a risk worth taking for him; he sought relief from pain at any cost.

It was too much for Coleridge to confront the reality that his creative power was on the wane, the kind of power that he saw in abundance in the likes of Wordsworth, Southey or Lamb was not his any more. He hardly could bear to watch his creativity slowly but surely drain out of his life, leaving him to dally with dull and dreary metaphysics. The wound was deep and he always ran after artistic or other gimmicks to paper it over. But he also needed narcotics to help him along.

This story of his addiction is as infamous as the story of his reverencing 'superior ' figures. The vacuum made by the gradual dwindling away of creativity forced him into a continuous, often pathological, search for tutelary figures who would work as buffer between the poet and the harsh world outside.

The problems of Coleridge's life somehow found a way into his art. The failure to get the co-ordinates right between his life and work is the prime reason why Coleridge, the man and poet, is an enduring mystery for us as he was for Wordsworth, his great contemporary and 'friend.'

The whole point of our discussion is neither to advertise the excellence of Coleridge as a poet nor to re-calibrate his place in the pedigree of the celebrated Romantics. The point is that when we have occasion to talk about imagination as a potent human faculty, we also need to be aware that factors such as the 'background' and the 'mental composure' of the poet also warrant attention in relation to the exercise of imagination. Coleridge is perhaps a great example of literary misinterpretation that follows when a poet is fatally wrenched from his intensely lived experience.

Unlike Wordsworth, Coleridge did not subscribe to the opinion that imagination is necessarily joyful. Too many things are at stake in our mental life for our imagination to keep discovering grace and beauty everywhere. Crises in life, big or small, find introjections into our psyche, often with the effect of benumbing its natural function. Creative writers are known to experience this phenomenon. No wonder that it was Coleridge himself who coined the term 'psychosomatic,' and not some scientist. And it is very fitting that Coleridge, as he experienced the mood of dejection slowly taking over and a long squally night weathering out, has the following lines to say--

A grief without a pang, void, dark, and drear,

A stifled, drowsy, unimpassioned grief,

Which finds no natural outlet, no relief,

In word, or sigh, or tear—

Yasif Ahmad Faysal teaches in the Department of English at Barisal University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments