Rape, impunity and power: 18 years after the anti-rape movement at JU

Today, as we mark 18 years of an incident that took place at Jahangirnagar University (JU), the nation is shocked at the media reports of the rape of a teenage girl by Tufan Sarkar, the convenor of Bogra District Sramik League. His crimes went beyond the rape: he humiliated both the victim and her mother with the assistance of his followers and family members. All of them are believed to be closely connected to the ruling party. Citizens from all quarters of society either took to the streets or penned protests against this dreadful act and demanded speedy justice.

The incident took me back 18 years, when we were left with no choice but to secure our beloved campus by storming, barehanded, into the dormitories which were then occupied by the armed cadres of the student group of then ruling party, known in the campus as the "Rapist Group". It was led by the Jashim Uddin Manik general secretary of the students' wing of the ruling party. One can blame us for taking the law into our hands. But what would you do if you heard that fellow students had been raped and the authority had refused to heed the allegations? What would you do if some so called intellectuals either remained silent or worse, penned against the student movement? What would you do if you were thrown out of your dormitory for demanding justice?

"Thousands of students were left with no choice but to leave their dormitories fearing for their safety. Parents rushed to the campus to take their sons and daughters back home. Those of us who refused to leave, became a part of, what was to us, a 'revolution'.

You were left with two choices: either you remained silent or spoke out. We chose the second and the major credit for that goes to our female colleagues who risked their lives and raised their voices for justice. The movement started in August 1998 and lasted until October 2001. In October 1998 some culprits including Jashim Uddin Manik were expelled permanently from JU, while others got off with expulsions ranging from several months to a few years. But, the university authorities did not file any criminal case and none of the culprits was tried under the existing laws. Immediately after the verdict of the university authority, their rivals from the same party, stormed into the campus and took control of the university. As the alleged rapists were not tried and convicted under the law, they too were looking for every available opportunity to regain their lost control. Heavily armed, they entered into the campus and ousted their rivals in July 1999.

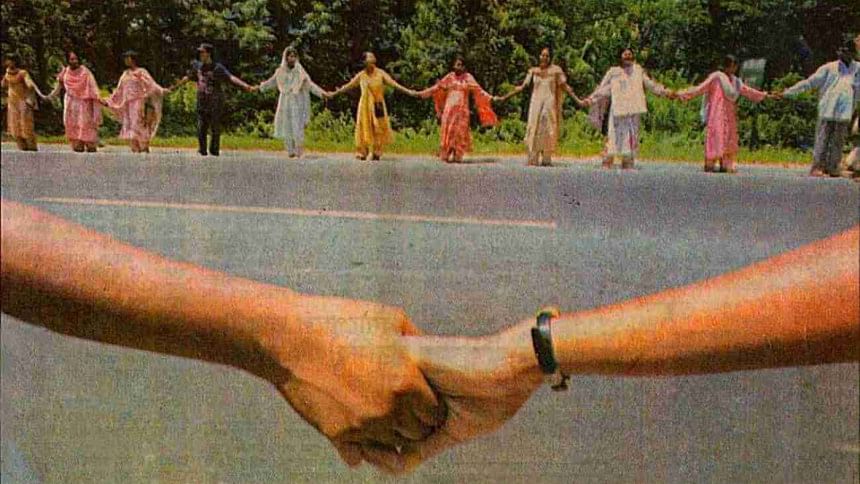

Thousands of students were left with no choice but to leave their dormitories fearing for their safety. Parents rushed to the campus to take their sons and daughters back home. Those of us who refused to leave, became a part of, what was to us, a 'revolution'. On August 2, 1999, several processions comprising thousands of students (mostly females) stormed the student dormitories in a bid to oust the rapists. Ultimately, they were successful.

But this was not the end of the story. In October 2001, seven students from Bangladesh Students Union, Socialist Students Front and Bangladesh Students Federation were expelled and 52 others were served with show cause (why they should not be expelled) when they organised a movement against the university authorities' attempt to allow a rapist to sit for a departmental exam. Finally, it took a High Court decision to nullify the authority's unjust action.

The above is neither an opinion nor an analysis. It is a chronology of certain events that took place during those four years at JU. The idea of penning this is to highlight how the combination of power, crime and impunity can turn an individual wealthy and powerful within years. The odds that we faced in Jahangirnagar more than a decade ago are very much the same with today's Bogra rape case. Things have not changed much over time. Tufan Sarkar is the latest example of how an individual can become powerful with the blessings of party men, and dare to commit crimes with the confidence of being above the net of law enforcing agencies.

Let us go back to JU once again. In April 2016 a canteen girl was raped. Left leaning student organisations demanded justice, but the university authority refused to take any measure since she was not a student. The state too did nothing since she was poor and helpless. Under pressure from the students, the canteen owner filed an abduction case. Police accepted the case, but there was no proper investigation. Her father rather felt it would be safer to take her back home. But irony was still awaiting her: she had no choice but to return to her workplace to earn her living and support her family. To cut it short, she never saw justice—thanks to a system that tends to serve the powerful and influential.

The Banani rape case that took place in March this year is yet another example of how our faulty system tends to work in favour of the criminal. The media's exposure of these crimes helped the protesters gain some ground. But one wonders why things have to move this way. The JU rape case became a major propaganda tool for the then opposition in the national election of 2001. But, sadly when they came to power, they did nothing to bring the culprits to book. Such is politics. It is time to look back into the political process so that we do not give birth to such monsters anymore. The justice system too needs to be carefully examined so that criminals do not continue to go unpunished.

Meer Ahsan Habib is a development professional.

E-mail: [email protected]

Comments