Get into a novel via virtual reality

The revolutionary field of digital humanities - all the rage in the US and Britain - is gaining ground among local universities.

You are frying kidneys in the kitchen as a black cat - the "pussens", you call it - winds its way around the table. You follow it into the hallway, where there is a letter on the floor. As you pick it up and read it, smoke begins to fill the hallway. The kidneys are burning.

Welcome to the world of Joycestick, a 3D virtual reality game that takes you inside Irish writer James Joyce's Modernist novel Ulysses.

The game, created by students from American private university Boston College, allows players to explore scenes from the novel via a virtual reality headset and joysticks.

Joycestick made a stopover in Singapore two weeks ago as part of the International Association for the Study of Irish Literatures conference at Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

The conference's emphasis on the digital humanities signals a growing recognition among local universities of this revolutionary field, which has been all the rage for some years now in universities in the United States and United Kingdom.

The idea of using cutting-edge technology to better study the arts and humanities may seem incongruous at first, even blasphemous. Can you really code Coetzee or distil Dickens into data?

Traditionalists who prefer poring over the page tend to be horrified that digital scholars want to feed centuries of classic texts into machines.

But for scholars such as University College Dublin literature professor Margaret Kelleher, the digital humanities represent the new horizon of academia.

The 53-year-old, who runs a digital platform for contemporary Irish writing and was in town two weeks ago to give the keynote address at the NTU conference, says: "The humanities have always been about innovation."

The first wave of the digital humanities is usually digitisation, she explains. This step is especially valuable to those who study ancient material.

"In the past, we would have to put on white gloves and spend hours in the archives with the only surviving copy of a manuscript. Now, more and more resources are digitised and put online."

The next - and more controversial - stage is using technology to analyse and interpret the material.

University College Dublin's Jane Austen Social Network project, for instance, uses network imaging to visualise relationships within the Regency-era author's works.

In the case of Joycestick, its creators hope that giving users a flavour of Ulysses through game play will help draw them into Joyce's famously difficult tome.

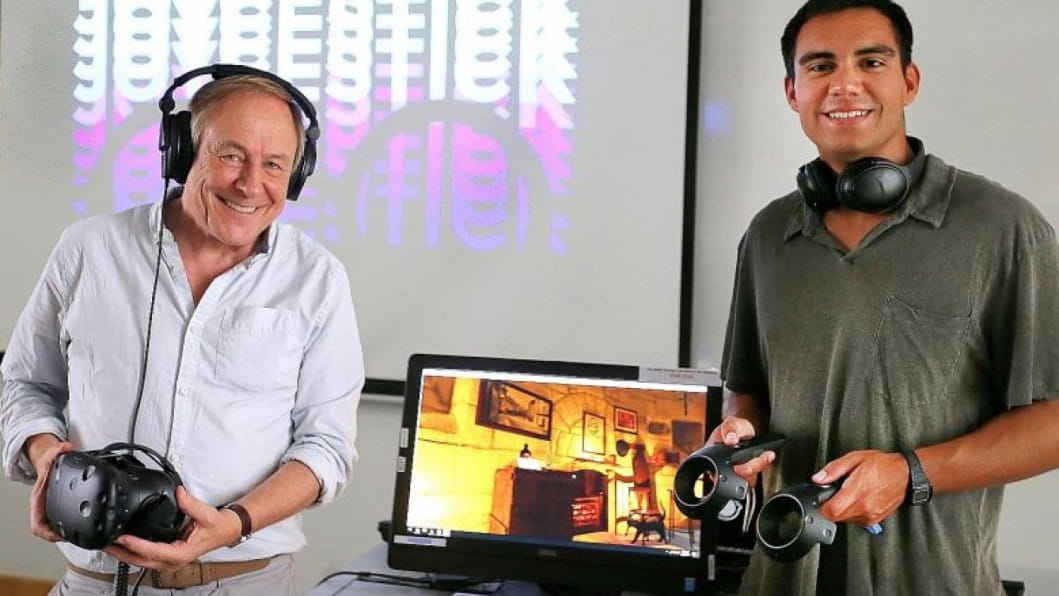

Project leader and literature professor Joseph Nugent, 62, says: "The kind of people who play video games aren't usually the kind who read Joyce, but we hope to change that."

The game, which took 25 students more than half a year to create, allows users to wander through settings from the novel, such as protagonist Leopold Bloom's home at 7 Eccles Street.

It features 100 3D objects - from a bowler hat to a death mask of Joyce, who died in 1941 - that players can pick up, examine from all angles and even throw across the room, while listening to audio about the object's significance.

NTU literature student Saiful Azri, 24, who tried Joycestick during the conference, found it "disorienting at first, but really quite immersive".

"Virtual reality is what our generation was brought up with and this definitely helps to contextualise the book for my understanding," he adds.

"In a way," observes Prof Kelleher, "reading a novel was the original virtual reality experience."

While digital projects have popped up here and there in Singapore over the years, it is only in the last few years that they have begun to consolidate forces under the flag of the digital humanities.

Two years ago, National University of Singapore Libraries set up a digital humanities team, which is behind projects such as a spatio- temporal map of Chinese clan associations and an online gallery of mixed-media artworks about places of worship.

Although technological obsolescence and the need to keep updating location data present constant challenges, NUS Libraries continues to maintain them as well as create new projects.

University librarian Lee Cheng Ean says: "With technological disruptions and scholarly content increasingly being born digital or being digitised for preservation and to increase accessibility, the opportunities for digital scholarship and digital humanities are endless."

It is a "fascinating moment" for digital humanities in Singapore, says NUS assistant professor Miguel Escobar, who runs the Contemporary Wayang Archive, an online repository of Javanese wayang kulit performance footage.

The theatre researcher, who is Mexican, is working on a computational model that could measure differences between character styles to learn how dances change across time and regions.

He is the convener of Digital Humanities Singapore, an unofficial association with 30 to 40 core members. They aim to bring together researchers across different disciplines and, earlier this year, held an international conference about metadata.

He is careful to note that digital methods are meant to supplement, not replace, traditional ones. "In other places, there are researchers who claim that you can do something completely different and there's no need for conventional tools. I think that's a mistake."

The digital humanities scene in Singapore may be at a nascent stage, but NTU assistant professor Graham John Matthews expects it to grow exponentially.

The Briton, who came to Singapore a year ago, is among the first to explore digital humanities at NTU and is building up a data set of epigraphs from English-language novels the world over. He is halfway to his target of 20,000 epigraphs, which give an idea of whom the author of the book liked to quote.

"We were trying to find a way of measuring literary influence that was more empirical," he says. The idea is to build a map of the world on which lines of influence can be traced geographically across time.

"We're just looking at a very small part of individual texts and using economies of scale to build up a larger picture. There has been a lot of support from colleagues here for the digital humanities. Soon, it's going to be one of those things that everyone does."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments