Too close for comfort

Harrowing messages from strangers that make us laugh more than they actually harm us, have turned "stalking" a carelessly tossed around phrase – if you're young and attractive, you're "supposed" to have stalkers. But it is this same culture that breeds actual stalkers, who violate all concepts of privacy and public decency to cause harm to everyone involved. It's important to know what counts as stalking, to talk about our experiences of having been stalked, and to know when to seek help.

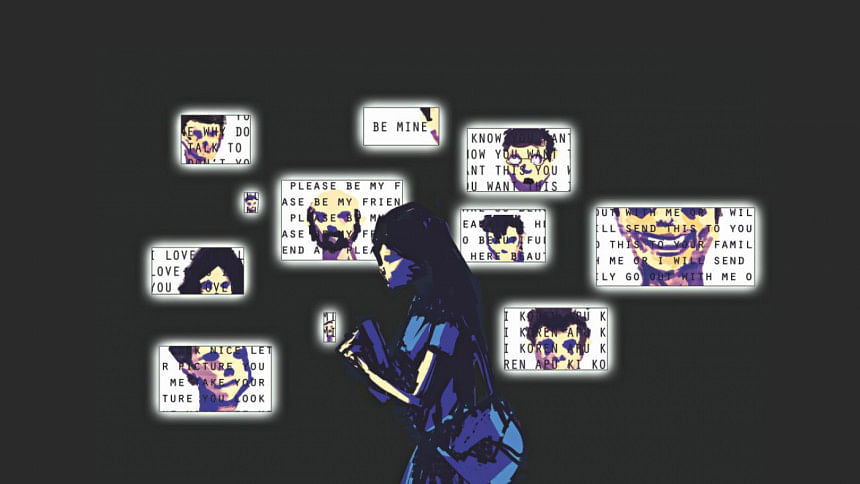

The actual definition of stalking can be, and in fact should be, subjective. It varies with each person's idea of personal space – when persistent or unwanted attention violates your consent, and pushes you to feel unsafe on social media or in real life, it most definitely counts as stalking. "'Appy nyc lagca' comments on pictures are unwanted attention, but when someone downloads your pictures and starts uploading them from his Facebook account, that counts as stalking," says Samia* in reference to her own experience.

Samia, currently a student at a public university, was teased and catcalled when she visited a renowned all-male college as a school student to hand out invitations for a science festival. But when a guy from that college texted her to make formal inquiries about the event and behaved perfectly politely throughout their acquaintance, she saw no harm in accepting his friend request on social media. It was when his behaviour got strange afterward that she restricted his access to her profile, and later blocked him from Facebook altogether. "A few days later, I found out that he had downloaded my picture, sketched it and uploaded it as his cover photo. A friend of mine texted him about it and after many swear words and threats, he removed it and stopped harassing me online," shares Samia. Unfortunately, this wouldn't be the last time that her privacy would be flouted on social media.

Samia recently started receiving persistent messages online from a student of another all-male college student who claimed his "undying love" for her in Anime language. He kept on pestering her with text messages through a mutual friend even after she blocked his profile on Facebook. Upon visiting the profile of the mutual friend, Samia found, once again, that her pictures had been downloaded without permission and uploaded from that account. She was luckily able to resolve the issue with help from a friend who also goes to that college.

Aasif*, a recent graduate of a private university, had a similar experience. He started receiving cryptic messages from an apparently fake Facebook profile a few months back. The person warned Aasif to stay away from a girl he was acquainted with, continuing for almost a month. "I started getting concerned when I noticed that he was using my photo as his profile picture! The profile would be deactivated shortly after sending the messages, so I couldn't report or block him," explains Aasif. "It made me more self-conscious about my social media activity, as well as my interaction with the friend in real life. I wasn't sure if I should share it with anyone – I didn't want to cause my friend any concern, but I was worried about my own privacy at the same time."

As harmless as these incidents seem, we're well aware of how wrong internet stalking can go, from scorned admirers "morphing" a person's face onto another's body, to abusive partners keeping pictures or videos that may or may not have been taken with consent. The blackmail that such pictures and videos make possible pushes many people to the point of self-harm and even suicide.

Section 8 of the Pornography Control Act 2012 makes it illegal to record and publish, electronically or in print, such compromising content, even with the consent of the person in the picture. Anyone convicted of the crime can face up to 10 years in jail and a fine of BDT 5 lakh if the person in the picture or video is younger than 18. But how many of us, younger than 18, know about these laws? More importantly, how many of us can scour up the courage to speak to our parents or guardians in such a scary situation, and hope to receive help and support instead of being blamed for it?

"'Shobar toh shomoshsha hoy nah, tomar keno hoy?' is what my parents often ask," shares Nasreen*, a high school graduate who will soon be starting university. Nasreen had been walking with her boyfriend in Uttara one evening, when she noticed a car and a man on a bike trailing them for a while. After a while, when she got onto a rickshaw to go home alone, the bike zoomed around the rickshaw, blocking her way.

"I saw him slow down in front of me. He looked me dead in the eye and started yelling obscenities at me. I saw the car parked just around the corner. I froze in fear. My rickshaw-wala panicked and wanted me to get off. The entrance to sector 10 gets eerily dark. I thought of what could happen if I urged the rickshaw-wala to take me further or if I got off the rickshaw," describes Nasreen. She decided to wait inside the closest grocery store nearby, watching the man on the bike waiting outside the store, until her boyfriend came back to take her home. Even though this was a one-off incident, its impact was jarring. Nasreen feels less confident about travelling alone now, and the psychological torture of imagining what might have happened if she'd turned into a more secluded street continues to traumatise her. What's worse though, is that she saw no point in telling her parents about the incident. "I have been subject to a lot of shaming in my life, even inside my own home. It is gut-wrenching to have to justify why strangers would harass me," says Nasreen.

Asked about why most teenagers and adolescents hesitate to seek help, Aasif points out that, "It's about the culture we're raised in and the society. Guardians tend to consider these incidents as 'playing with fire and getting burnt'. They often fail to understand that being stalked is never a choice. They need to be more open-minded if they want to help us."

Meanwhile, Anika* faced a more terrifying experience when she was in university, a few years ago. A man she had taken coaching classes with earlier introduced himself in one of her university lectures. What started off as harmless gawking escalated to following her around at campus events, threatening texts and emails, and scary phone calls to her home number. He had collected her phone number and e-mail ID from the attendance sheet in class, and used them to berate her for interacting with other male students and wearing clothes that he "didn't approve of". It stopped, finally, when Anika's father spoke to him on the phone.

While stalking of girls has at least started to generate constructive discussion these days, what goes completely disregarded is the fact that men can be stalked as well. No one, unfortunately, takes these issues seriously, instead ridiculing the man for feeling threatened by a stalker.

Namir*, a student of a public university, explains how safety concerns have nothing to do with gender, and neither do they have a fixed definition. "It's annoying when you are repeatedly being spoken to by a person you do not want to engage in conversation with; when they ignore your boundaries of personal space."

Namir was stalked by a former girlfriend who started skipping school to hover around his classroom and his house, hiding from plain sight but clad in her school uniform, which naturally drew attention. She would add Namir's friends on Facebook and pester them about his whereabouts, and leave flowers and letters with the guards at Namir's school, which got him in trouble with the school principal. It stopped when Namir spoke to the girl's parents, suggesting that they pay more attention to where their daughter was going regularly.

"There was literally no way that it would've stopped without parental intervention," explains Namir. "It was difficult to convince her parents initially, of course. They accused me of lying about their daughter. But the stalking did stop, so I know what I did was right."

We live in a society that struggles with the nuances of consent and privacy, making fun of a guy whose privacy is violated, and blaming a girl for even expecting others to respect it. It is this bizarre gap of communication and lack of empathy that caused 158 people to be injured by attacks from stalkers last year, according to media reports. Sixty-one people stopped going to school in fear, and 20 people died. Not all of them were girls. Being from privileged backgrounds may accord us the safety from these more gruesome manifestations of stalking, but there's no concrete guarantee of safety. It certainly doesn't mean that we can keep ignoring its urgency, and let attacks on our privacy fly by.

*The names of the interviewees have been changed due to their request for anonymity.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments