The low employment growth puzzle

The slow growth of employment between 2013 and 2015-16 is the most important observation emerging from the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) 2015-16 data, which was released recently by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

During the two and a half years, employment growth per year was 5.6 lakh -- much lower than the growth during 2010-2013 period, when it was 13 lakh per year. The employment growth was even higher during 2006-2010.

The slow employment growth can be explained by: the rising capital intensity of various manufacturing sub-sectors; the jobless growth across all sectors; and preoccupation with GDP growth, leading to disregard for policies related to employment generation.

These factors, however, cannot be substantiated with actual data except in case of garment sector, where some data on the rise of capital intensity and stagnation of employment are available.

The government's direct employment generation programmes as part of social safety net continued without much change during the period, and in some projects, expansion has taken place.

On the front of self/family employment, there is again no reason why the number would decline.

Another factor contributing to the decline of employment may be the reduction of supply. However, this cannot be established on the basis of QLFS data.

The indicator of supply is labour force participation rate, which takes the values of 57.1 and 58.5 percent in 2013 and 2015-16 respectively, thus indicating no decline in the supply side.

A sharp decline of employment without much change in relevant policies thus remains a puzzle.

Under-enumeration can at least partially account for the observed slow growth of labour force and employment.

Doubts about employment and labour force data of 2015-16 arise from the fact that the age distribution of the population obtained from the latest and the previous Labour Force Survey (LFS) is drastically different.

In 2013, about 30 percent of the population was below the age of 15. This has increased to 33 percent in 2016.

With a continuously declining total fertility rate over the last two decades there is hardly any rationale behind the sudden increase in the share of child population. It is likely to be due to under-enumeration of adult population.

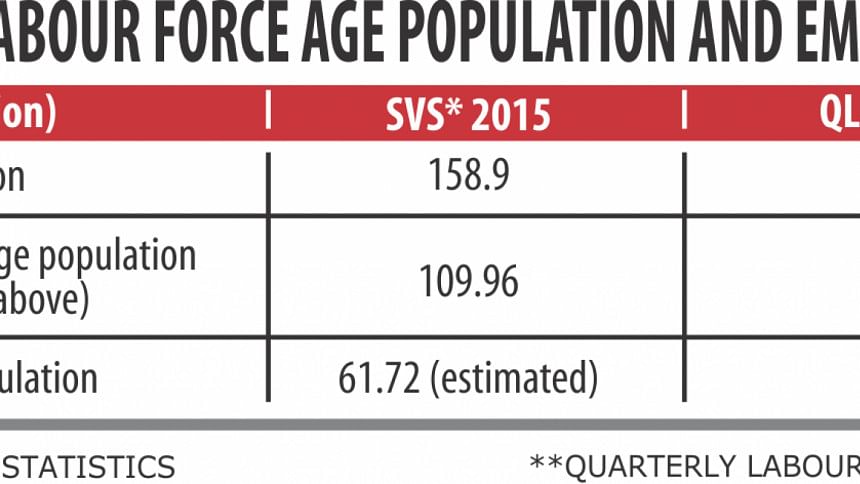

There are 10.6 crore people aged 15 years and above, according to LFS 2015-16. Soon after the release of LFS data, the BBS released the “Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics (SVS) 2015”, where the size of the same age bracket was given as 11 crore.

This suggests the LFS showed 40 lakh less persons in this age group. Assuming the same employment rate for those not enumerated and those actually enumerated, about 22 lakh more would be in employment on the basis of SVS data.

This gives a figure of employment growth of about 36.2 lakh in 2.5 years and 14.5 lakh per year during 2013-16, which is slightly higher than the 2010-13 figure.

However, this is based on a number of assumptions and cannot be confidently used as a basis for policy guidance.

Moreover, if the proposition of under-enumeration is valid, then one cannot obtain the distribution of employed population by sector, status and so on from the revised data proposed here.

It is likely that those left out would have a larger share employed as self/family worker. This may explain why the current QLFS shows a decline in this type of employment.

During the last few years, various policy documents including the seventh five-year plan of Bangladesh have highlighted the prospects of utilisation of youth labour force, often termed as a demographic dividend, for acceleration of GDP growth.

It has been envisaged that in the coming years youth labour force will continue to grow and the increasing size of the youth labour force will provide an elastic supply of labour for the modern sectors of the economy.

However, the size of youth -- those between the ages of 15 and 24 years -- labour force was 1.34 crore in 2013 and 1.17 crore in 2015-16. This implies that the demographic dividend is on the wane.

Nonetheless, even the revised estimate of larger size of employment may not imply an overall positive scenario of the labour market.

The most important indicator of improvement in this context is income from wages, and data from the two LFS show that between 2013 and 2015-16 the average earnings rose 12 percent in nominal terms.

In real terms, there is hardly any increase since inflation during the two and a half years was more than 12 percent.

Stagnation of real wage is likely to be associated with the expansion of labour supply at a rate higher than the demand for paid employment. Therefore, a sustained growth of real wage requires creation of paid jobs at a faster rate.

LFS data for the unskilled occupations show that real wage per month has gone through a decline, which is in conformity with other data on wages provided by the BBS.

Given the uncertainty about working age population and employed population, the question is how to use LFS data for further policy related analysis.

Since BBS has plans to conduct LFS every year, it is being proposed that a fresh round be conducted immediately. This should not be based on panel survey using earlier sample, which then will have the same problem related to enumeration.

For simplifying the data collection and tabulation process, a much shorter questionnaire with selected key questions may be used.

There is a risk that this may again introduce a bias to show high employment growth. Steps must be taken to remove biases from such preconceived notions.

The writer is a director of the Bangladesh Bank board and executive chairperson of the Centre for Development and Employment Research.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments