In conversation with Tanvir Mokammel

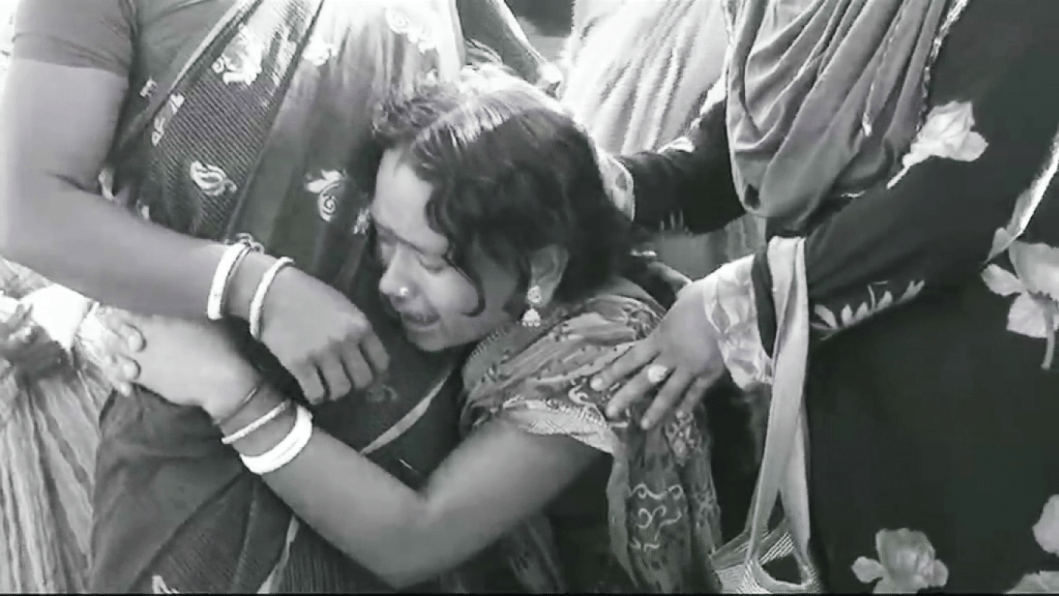

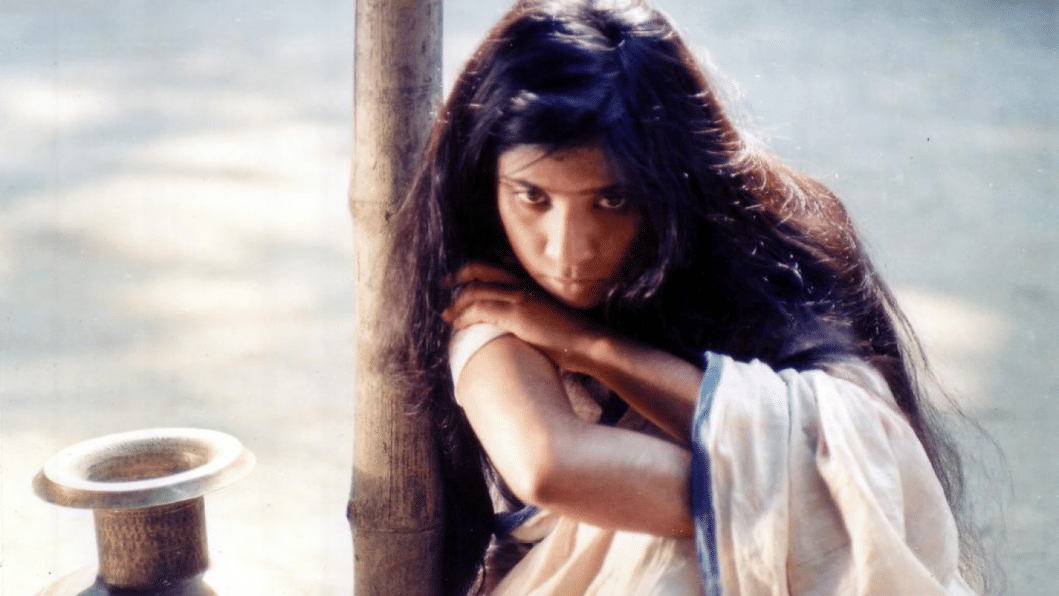

Tanvir Mokammel is an award-winning film-maker from Bangladesh, critically acclaimed for his historical and political commentaries in films such as Nodir Naam Modhumoti (1995), Lalsalu, (2001) and Jibondhuli (2014). He remains the only filmmaker from Bangladesh whose work has focused on the partition in a comprehensive manner. His feature film Chitra Nadir Pare (1999), which won seven national awards, follows the life of a Hindu family in the then East Pakistan. His latest project, Seemantorekha, is a documentary about the Partition of Bengal, the arbitrariness of borders and its effects on a people displaced. The documentary is in its post-production stage.

In an interview with Star Weekend, Mokammel talks about the significance of 1947 in his films, the role of artists in documenting history and the amnesia surrounding Partition among Bangladeshi filmmakers.

Why has the Partition featured so prominently in your life and in your work?

The reasons, I guess, are two-fold. In my conscious mind, in the socio-political-intellectual plane, I believe that the Partition of 1947 was the root cause for all the anomalies we are suffering from in our present society now.

Another reason, I guess, lies in my subconscious. Bengal had been a cultural entity for more than 2000 years. By dividing Bengal, the very existence and emotions of our Bengali identity, our deeply rooted cultural traits have been shattered. It is true that Bengal, in different times in history, remained divided in different states—Somotot, Rar, Harikel, Barendra etc. But never before the 1947 Partition was the division so decisive, so complete. Never was a barbed wire erected between our Bengali population. Hence, the Partition of 1947 haunts me with a great sense of loss, and it keeps figuring in my films and writings repeatedly, like a leitmotif.

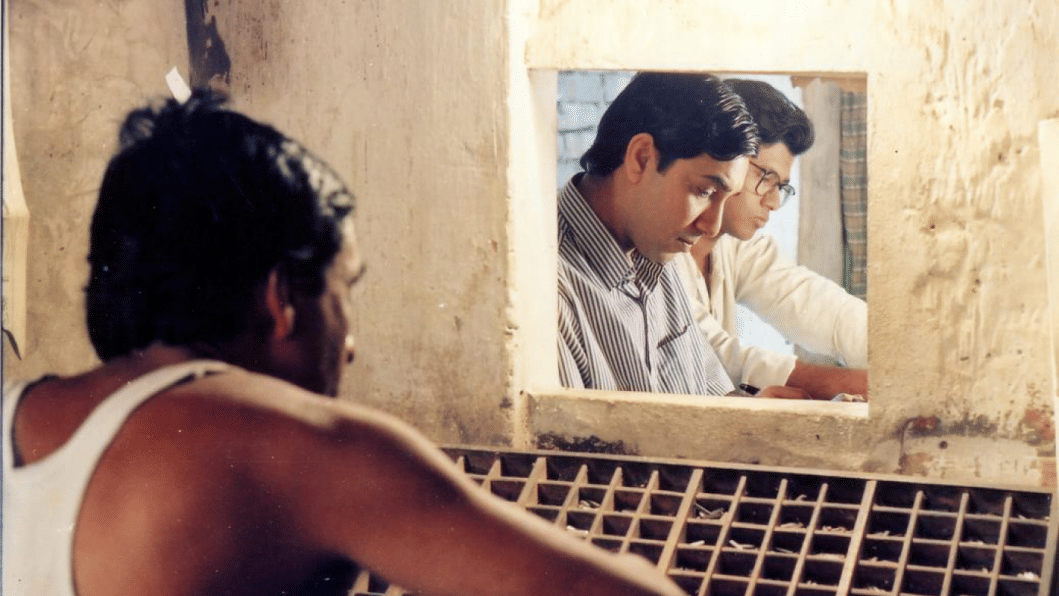

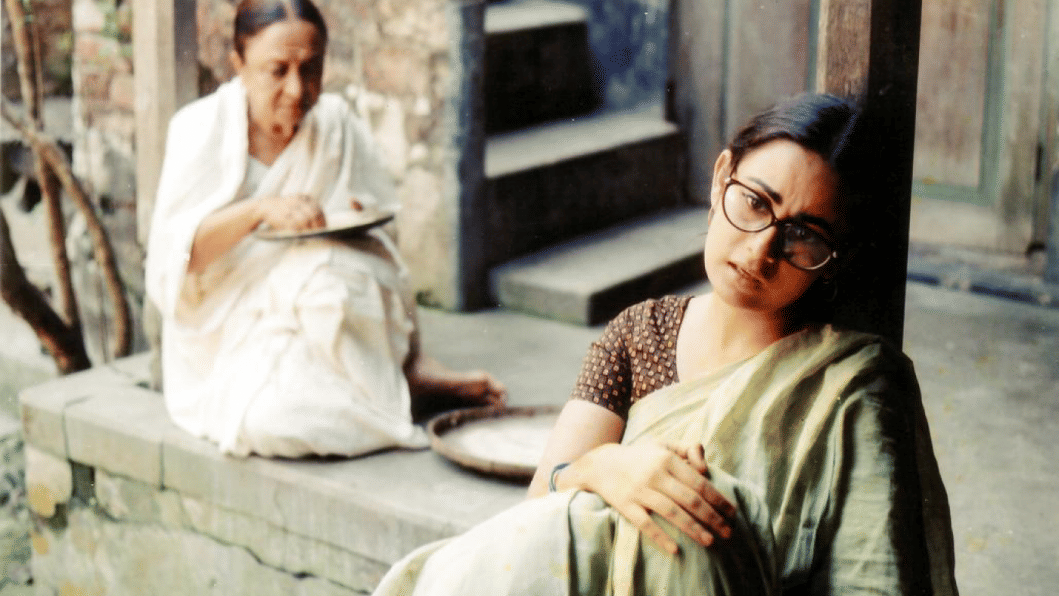

Your film Chitra Nodir Pare emphasises the little-talked-about 1964 riot and the migration of the Hindu population to India. Why did you choose that as your subject?

An artist generally portrays what he has seen or experienced. I saw the 1964 riot. Though I was a mere boy at that time, I vividly remember the event. I grew up in Khulna and before the 1964 riot, Khulna had a huge Hindu population. In the pre-partition days, the Hindu population in Khulna district, in fact, constituted the majority—51 percent. So, a lot of my childhood friends from school, and the boys from my locality with whom I used to play, were Hindu. They left Khulna (and also the then East Pakistan) after the 1964 riot. For me, that was a deep shock. I still miss my childhood friends!

Besides, my mother was a very courageous woman. She used to teach in a local college. During those riot-torn days, my mother would go around Khulna town in a rickshaw, pick up her Hindu colleagues or students, mostly female students, and some families she knew, and bring them to our house. These families stayed on the ground floor of our house, Mokammel Manzil, for weeks during and after the riot. Their anxious faces perhaps left a strong impression on my young, tender mind. You will be surprised to know that when I was just a student of class six—I mean around the age of 11—I decided to make a film on the miseries of the Hindus in East Bengal and decided to title the film Chitra Nodir Pare!

And why Chitra Nodir Pare? Because during the 1960s, my father worked as a magistrate in Narail, a mofussil town on the bank of the Chitra river. I remember many families from there who were either migrating to India, preparing for it, or still indecisive about whether to leave or not. A Hindu lawyer's family used to live just next to our house in Narail. The girls of that family were friends of my sisters. One day I heard that the lawyer was telling my father: 'Mokammel Saheb, I will never leave Narail. I will not be happy even in heaven if I leave the banks of the Chitra river.' Perhaps that statement made an impression on me. The lawyer Shashikanta Sengupta, the main protagonist of the film Chitra Nodir Pare, to some extent, was modelled after that Hindu lawyer who had refused to leave East Bengal.

Ritwik Ghatak once said in an interview that the innate connection between his three films Meghe Dhaka Tara, Subarnarekha and Komol Gandhar is the unification of the two Bengals. But in Chitra Nodir Pare, the lead female character Minoti and her father Shashikanta Sengupta seem to detest the idea of migrating to Kolkata, though Shashikanta's son went there after 1947. How do you define the differences between your portrayal of the Partition and that of Ritwik Ghatak?

Ritwik Ghatak is a great filmmaker and his works should not be compared with my modest efforts. The three films of Ghatak that you have mentioned form a kind of a trilogy on the 1947 Partition. Rich in symbolism and metaphors of the Mother-Goddess, Ritwik's films mostly dealt with the tragic effects of the Partition on the refugee families uprooted from East Bengal. In his films, the pangs and pathos of the divided Bengal figured in a tragic and archetypal dimension. Chitra Nodir Pare, on the other hand, mostly deals with a sense of loss, the loss that East Bengal suffered due to the mass migration of the culturally rich Hindu populace from this land. But you have to understand that Chitra Nodir Pare is a very low-budget small endeavour, shot in 16mm only. The film should not be compared with the masterpieces of Ritwik Ghatak. The only comparison that can be drawn is the deep sense of loss, which we both as filmmakers, felt about the Partition of Bengal. He has shown the tragic consequences of the Partition from that side of the border, and I have tried to do that from this side of the border.

Tell us a bit more about your new work Seemantorekha (The Borderline)? Which border areas did you choose to shoot for your film?

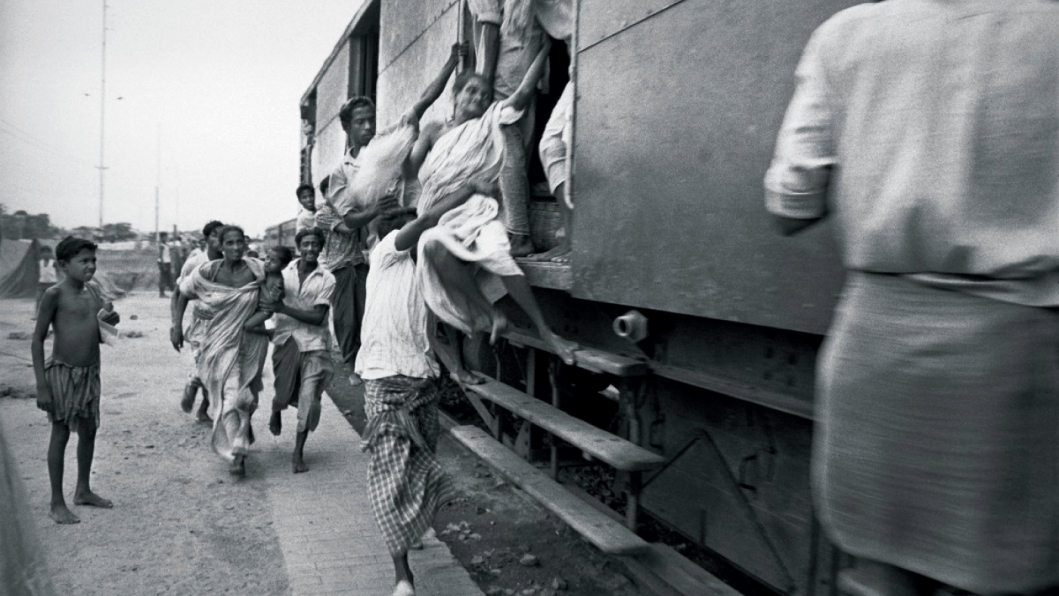

Seemantorekha is a two-and-a-half hour documentary on the Partition of Bengal. 2017 happens to be the 70th anniversary of the Partition of 1947. Seventy long years have passed, perhaps it is now time to look back at this historical event. Who has gained from the Partititon? Who has lost? The film analyses that history through human stories, and depicts the human costs involved in the Partition. We have researched for three years for the film Seemantorekha. Its shooting is complete now. We are at present working on the soundtrack and other post-production elements of the film. The film will be released sometime next month.

The one aim of the film is to find out what the borderline between the two Bengals actually means. Is it just a barbed wire at the border between two sovereign states, Bangladesh and India? Or is it a demarcation line drawn between the Hindus and the Muslims? Or is it a line to highlight the traits of cultural and behavioural differences which exist between the people of East Bengal and West Bengal? Or is there any invisible line within our hearts which do not let us mingle together? The film will be an attempt to explore these questions.

We have shot the film in quite a few places—mainly in the border areas of both Bangladesh and India. But we have also shot in the refugee camps, like Cooper's camp, Dhubulia camp, and Bhadrakali camp in West Bengal where refugees from East Bengal took shelter. We also shot in Dandakaranya in Madhyapradesh and Chottisgarh where refugees from East Bengal were sent, as well as in Nainital of Uttarakhand. We also shot in the Andamans where some refugees from East Bengal were resettled.

Besides shooting in different places of East and West Bengal, we have also shot in Assam and in Tripura. Due to the Partition, East Bengal (now Bangladesh) also lost its organic and historical contacts with these two neighbours. We want to highlight the different manifestations of 1947, especially the human costs involved in it, like the suffering of the refugees and the people who migrated. As an artist, for me, the human element is the most important concern.

What was the process of collecting oral histories like? What moved you the most about some of the stories you heard?

The idea was to shoot as many people as we could who had personally experienced the traumatic days of the Partition. We worked on both sides of the border. The story of any person, forced to migrate from his/her motherland, is always tragic and sad. But the stories which moved us the most were the stories of some very old women, who are still languishing in the old and deserted refugee camps of West Bengal, who have been dubbed as 'PL' or 'Permanent Liabilities' by the officials. They have become 'Permanent Liabilities' on our conscience! To me, these hapless old women are the worst victims of the tragedy called 1947 Partition.

What are the challenges to making films such as Seemantorekha, being of a political and historical nature, in an era driven by corporations and profit?

Making any serious documentary in Bangladesh itself is difficult, as there is little to no support—even understanding—of this kind of documentary cinema here.

Research was also a big challenge as the scope of the film was huge—embracing both the Bengals, Assam, Tripura, even the Andamans. We spent three years for research—it was difficult and time-consuming, to say the least. Shooting, at times, was also problematic as we had to cross the border so many times, and shooting in the border region, both in Bangladesh and in India, was never easy.

Finance also posed an acute problem. Cinema in Bangladesh is a profit-oriented affair, so no producer was available for this kind of a non-profit venture. In some countries, there are some art foundations or research organisations to help this kind of cinema. But Bangladesh simply does not have anything like that. So I started working on the film with my own meagre resources and taking loans from my friends and well-wishers. That's why the filming process of Seemantorekha was rather slow—often painfully slow! But at one stage, my resources drained out. We then made an appeal for crowdfunding to finish the film. And it worked. Many people came forward. One couple from the US, Dr Debashish Mridha and his wife Mrs Chinu Mridha, donated the bulk of the money. My film unit and I are deeply grateful to them. Seemantorekha is also the first documentary film in Bangladesh to have been crowdsourced.

What is the role of an artist in representing a tragedy such as Partition? Is it easier for artists to capture the human sufferings that occurred during Partition than for a historian?

When it comes to capturing history, to some extent, the job of an artist and an historian are the same—to seek and find the truth. Just because you are an artist, you won't be excused if you are untrue! So one has to be very meticulous in presenting history as truthfully as possible, and so, research remains a painstaking job. The 1947 Partition of Bengal is such a sensitive subject that you have to have foolproof research.

A historian may be then allowed to depict the historical events with a broad brush. But as artists, we cannot do that. We have to deal with living human beings, their individual stories, experiences and emotions. So we have to be very careful in presenting historical events from all their different perspectives, and their impacts on the lives of these human beings.

And finally, the film has to be presented in an aesthetic manner: Satyam-Sivam-Sundoram. As an artist, I have to present my work as truthfully, and at the same time, as aesthetically pleasing as possible. So, there seems to be quite a few challenges for an artist to present history, especially such a mammoth historical tragedy as the 1947 Partition of Bengal.

Would you say there is amnesia surrounding the 1947 Partition in films made by (other) Bangladeshi filmmakers? Why is that?

I am afraid the answer is yes. There is amnesia about the 1947 Partition among the filmmakers of Bangladesh. There are some well-meaning portrayals of the Partition in our literature, but unfortunately, not in our cinema.

The reason, I guess, is the general lack of sense of history. In our mainstream commercial cinema, you perhaps have noticed, there is very little, or no sense of history, at all. Even such a near and epic event like the 1971 Liberation War is almost amiss here. And 1947 is a much farther away event!

In the alternative film scenario, we do find some films made from a historical perspective. But unfortunately, Chitra Nodir Pare is perhaps the only film that deals with the tragedy of the 1947 Partition.

How has the Partition impacted the Bangladeshi film industry?

There is no direct impact or correlation. But there was an indirect impact. Cinema in Bengal was totally centred in Kolkata. East Bengal simply didn't have a film industry. But due to the 1947 Partition, when East Bengal became a separate state of Pakistan, the necessity of a film industry in Dhaka was felt. During the United Front (Jukto Front) government, in 1956, by the initiative of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, then a young Minister, the Film Development Corporation (FDC) was formed. Unfortunately, the well-meaning ideas that worked behind the creation of FDC have failed, and have failed, miserably.

Comments