After the holocaust: Partition and Bangladeshi literature

The Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 has become indissolubly linked to horrific, haunting images of armed gangs or mobs attacking helpless groups of men, women and children trying to cross a border that had just been scratched on the map. Literature registers the shock in works that make harrowing reading. Partition literature becomes a tragic sub-genre in the subcontinent. However, this image of Partition literature does not apply uniformly throughout the region. The massacre was centred on the Punjab. South India, mercifully, was spared the horrors. In the east the pattern of violence was quite different, and had a different sort of demographic and literary fallout. The holocaust in the Punjab left no Hindus or Sikhs west of the border and no Muslims to its east. In Bengal, instead of such wholesale demographic changes, there has been migration in spurts and trickles prompted by episodes of communal conflict.

Bangladesh is unique in that it has undergone the experience of partition three times; and each time it has been different from the other two. The first partition, which took place in 1905, and was repealed six years later, has mainly touched Calcutta-based writers. In 1947, Bengali Muslims wanted an undivided province to go to Pakistan, while Hindus favoured partition. The Muslim peasantry identified a dual antagonist comprising the Hindu zamindars and British colonisers. The opposition was further complicated by a class dichotomy among Bengali Muslims, with Muslim zamindars and their other upper-class coreligionists labelling themselves superior (ashraf) as opposed to the inferior Muslim common people (atraf). Consequently, two kinds of Muslim political formations emerged, Fazlul Huq's Krishak Praja Party claiming to represent the peasantry; while the Muslim League was dominated by ashraf politicians, many from the zamindar class. The internal dialectic of Muslim politics became a tussle between the two groups for the support of the Muslim masses, with the upper-class leaders happily falling back on the universalist message of Islam to paper over class differences. Similarly, there was a caste divide within the Hindu community, with some low-caste politicians demanding—unsuccessfully, as it turned out—a separate electorate.

Unsurprisingly, as soon as Pakistan was put together it began to show strain at the seams, first over the question of what would be the state language, then over economic disparity between the two wings. The demand for democracy and autonomy led to the six-point movement led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, whose popularity earned him the affectionate sobriquet of Bangabandhu, and eventually led to the independence of Bangladesh.

The price of independence was the most harrowing bloodshed ever seen in the country. A point often missed in accounts of the independence war is the attempt by the Pakistan Army to replay on its own terms the Partition massacres that took place in 1947 in and around the Punjab. From 1947 to 1971 West Pakistan's ruling elite blamed the disaffection in East Pakistan on the province's Hindu population and their influence on Muslim Bengalis, whom they considered insufficiently Islamised. What the latter had failed to do in 1947, because they were 'bad'—Hinduised—Muslims, the Pakistan Army was brainwashed into attempting in 1971. The Partition has cast a shadow from which the subcontinent has not emerged. Its effects are a part of the day to day lives of millions. Geopolitically, the militancy and civil unrest in many parts of the region are a direct consequence of Partition.

Perhaps the earliest fictional treatment of Partition by a Bangladeshi writer was the short story, 'The Escape', written in English by Syed Waliullah (1922-1971) and included in the Pakistan PEN Miscellany (1950). The locale is unspecified but can be taken to be North India, though it could be on either side of the newly drawn border, and the action takes place on a train, an iconic emblem of hope and horror in that region. Except for the detail of a skull cap on someone's head there is nothing to indicate the religious affiliation of the passengers, thus lending the story greater universality. The same effect is produced by an anonymous corpse lying on a station platform. A moving piece, it uses expressionistic devices to evoke the horror of what was happening: a character described as a madman by another, and who leaps off the running train; a story that the narrator's interlocutor is not interested in listening to and remains unfinished.

" Nostalgia is a powerful theme in Partition-related fiction from West Bengal, but not in Bangladeshi works. And so, when Taslima Nasreen forays into this theme it is with a Hindu migrant to India who visits her old home in Fera (1993).

Another story of Waliullah's that subtly captures the inner turmoil wrought by Partition on those who had become uprooted is 'Ekti Tulsi Gachher Kahini'. It features a group of refugees from India who break into and occupy an abandoned Hindu home. One of them finds a tulsi plant in a bedraggled state on the grounds of the house and wants to pull it out as it is sacred to Hindus. Another refugee, who has caught a cold, points out its medicinal value in treating coughs and colds, and the plant is spared. Someone quietly tends the plant so that it begins to thrive again. One member of the group invokes the railway train, the iconic symbol of the deracination caused by Partition, as he imagines the housewife who used to look after the plant travelling to another country. Through the mediation of the plant the dispossessed owners of the house and its illegal occupants come to realise their common fate. It unites them even though the squatters are voluble in castigating Hindus for the wrongs they have done to Muslims. Niaz Zaman in The Divided Legacy, the only book-length study of Partition literature by a Bangladeshi critic, aptly comments: 'Both the groups are homeless refugees, both forced to vacate their homes for an uncertain future in an unknown place…Despite religious and political differences, Waliullah suggests, the human bond remains somewhere underneath.' The story ends with officials evicting the squatters from the house, which has been requisitioned by the government. The tulsi plant, with none to water it, begins to wither again. The implication is clear; the suffering brought on by Partition is to be blamed on the impersonal decisions of officials.

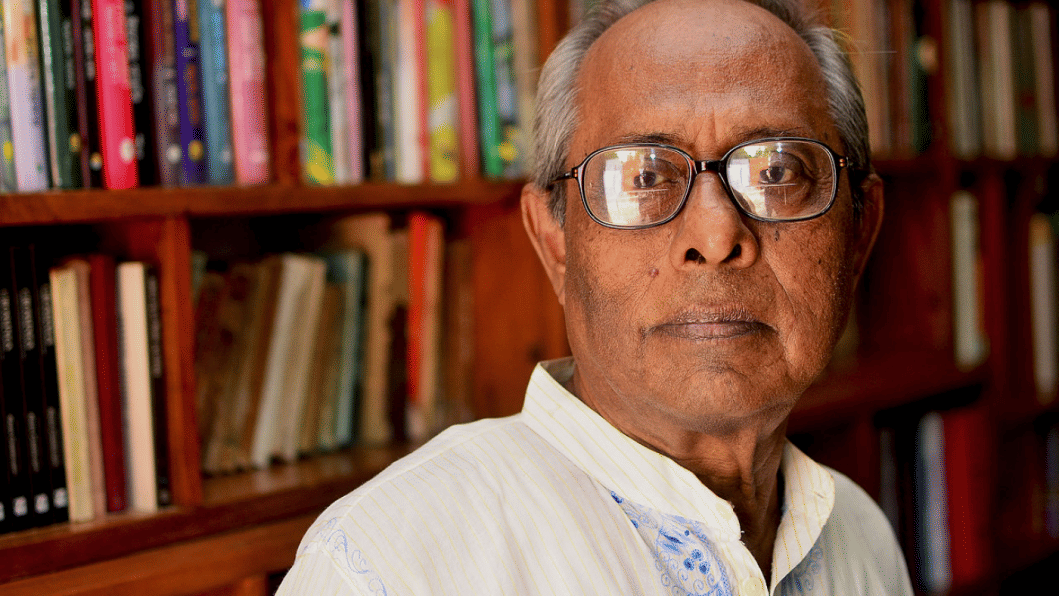

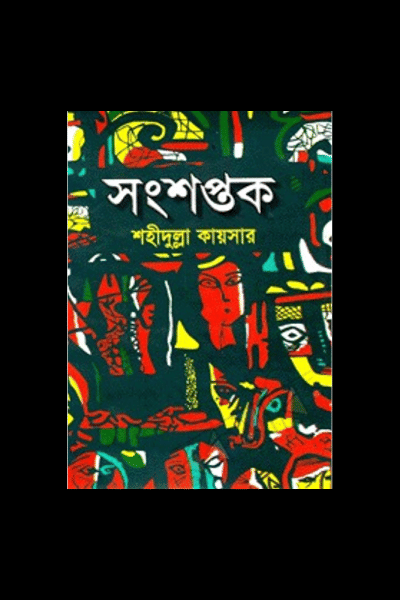

The first Bangladeshi novel dealing with Partition is Ranga Prabhat (1957) by Abul Fazl (1903-1983). Two novels, both Marxist in inspiration, focus on the anxieties and social tensions in the decades leading up to Partition, are Alauddin Al Azad's Kshudha O Asha (1964) Sardar Jainuddin's Anek Suryer Asha (1966). A much more ambitious novel is Shahidullah Kaiser's Shangshaptak (1965), which was also made into a highly successful television serial.

Shahidullah Kaiser (1927-1971) was not only Marxist-inspired; he was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party at a time when it was an underground organisation. The Communist Party of undivided India, though opposed to the dismemberment of the subcontinent, advised members to accept it as an inexorable historical reality and to carry on party activities in whichever country they happened to have their domicile. Kaiser therefore views Partition as a historical accident within the broad dialectical play of social forces and classes. His protagonist Zahed starts off as a committed Muslim League activist but turns later into a communist. The conflicts that led to partition give way to other conflicts, between West and East Pakistan, while the inherent class conflicts continue to impact on people's lives.

Abu Rushd's Nongor (1967), is the work of a West Bengali Muslim who chose to move to (East) Pakistan. It may be described as bourgeois realist fiction depicting the existential choices of a protagonist, Kamal, who is in many ways the author's persona.

Nostalgia is a powerful theme in Partition-related fiction from West Bengal, but not in Bangladeshi works. And so, when Taslima Nasreen forays into this theme it is with a Hindu migrant to India who visits her old home in Fera (1993). Her protagonist Kalyani comes back to Mymensingh only to be dismayed at the changes that have overtaken the place and the society.

Akhteruzzaman Elias (1943-1995) has produced a novel of epic proportions in Khoabnama (1997). Supriya Chaudhuri in her essay 'The Bengali Novel' describes it, with good reason, as 'possibly the greatest modern Bengali novel', a prose epic spanning a vast and diverse timeline and creating a distinctive kind of magic realism drawing on 'indigenous traditions of folk narrative, memory and legend, as on subaltern history.' The narrative opens with the fakir rebellion of the late eighteenth century, and follows the lives of later generations steeped in legends derived from that hoary age. Villagers bring up questions of sectarian differences of which the urban middle classes are hardly aware. Some characters affirm their identity as Muhammadi (that is, adherents of the Tariqa-e-Muhammadi, a Wahhabi-inspired sect). The ideological effort of the pro-Pakistan activists to paper over such crucial local differences is exposed as a ploy to ensure that leadership of the Muslims stays with a certain class. The problems of the tenancy system led to the Communist-led tebhaga movement around the time of Partition; this unsuccessful venture aimed to obtain two-thirds of the produce for the tenant farmers instead of the customary half.

Khoabnama received the Ananda Prize, the most prestigious literary award given in Kolkata, as did Agunpakhi by Hasan Azizul Huq (2006). Unlike Elias, Huq hails from West Bengal. He migrated to Pakistan in a most lackadaisical manner, as a brief interview reveals. In Burdwan, where his family came from, 'the Muslims of that area did not experience any real trouble,' he says. His sister's husband was an English teacher in a college in what had become East Pakistan. They asked him to live with them and study, so he went. After completing an MA at Rajshahi University he returned to Burdwan and took a job as a schoolteacher. After three months a visiting school inspector questioned his bona fide as an Indian, even though he had an Indian passport, so he came back to Rajshahi and settled there. He persuaded his parents to join him and his brother there, but his uncles and cousins stayed on in India even though they had supported the Pakistan movement. Agunpakhi is a first person account in the dialect of Burdwan of the life of a middle class Muslim woman who sees the organic community into which she had been born shatter under the impact of communal politics. But in the end she takes a stand and refuses to accompany her family to Pakistan.

I will end with a cursory look at the presence of Partition in the work of writers born after the event. A short story in English, Khademul Islam's 'An Ilish Story', published in the Bangladeshi journal Six Seasons Review, presents a scene in a middle class Bengali home in Dhaka in the aftermath of the independence war of 1971. The narrator has escaped with his family from Pakistan, where they would have been treated like prisoners. He watches his grandmother cut and dress a hilsa fish (ilish in Bengali). As she does so she narrates what she has seen and heard during the war. '"1971 was 1947 all over again", she says, as she holds both ends of the fish with her hands and vigorously saws it back and forth across the blade .' The description of the cutting becomes increasingly gory as she narrates how in her native district a maulvi led an attack on a Hindu family in the neighborhood.

Mahmud Rahman's short story collection, 'Killing the Water' (2010), includes a few pieces that sketch in the Partition as an unavoidable backdrop. Tahmima Anam's debut novel, A Golden Age (2007), links up Partition with the 1971 war through the family of 'Rehana Ali of Calcutta'.

It is an interesting facet of our current cultural climate that the younger generation is drawn to a critical examination of the trauma of Partition in order to see their historical situation in perspective. An anthology of graphic narratives issued in 2013, This Side That Side: Restorying Partition, curated by Vishwajyoti Ghosh, brings together the attempts of writers and artists from Pakistan, India and Bangladesh to deal with the existential spin-off of the event. When the book was launched at the Dhaka Hay Festival in November, 2013, all seventy copies brought over sold out in record time; and so would have three times that number. Six of the twenty-eight stories are by Bangladeshis. Mahmud Rahman's 'Profit and Loss' is an autobiographical sketch moving from the Partition and the problems that came in its train to the 1971 war. Khademul Islam's 'The Exit Plan' narrates the adventure of escaping from Pakistan where he would have been incarcerated as an undesirable alien. M. Hasan's 'Making of a Poet', Syeda Farhana's 'Little Women,' and Sanjoy Chakraborty's 'An Afterlife', delve into facets of the identity crisis in our fractured subcontinent.

My own contribution, 'Border,' is a poem that tries to expose the existential consequences of having a shadow line scoring the region's map. It is based on an overland trip I made to India years back. In the poem the journey is prompted by desire, for where there is a boundary there is fascination with the other side: 'Let us say you dream of a woman/ and because she isn't anywhere around,' imagine her across the border.' After a mildly nightmarish journey to the border, the speaker 'instead of crossing over' lies 'dreaming/ of the woman, and the border: perfect knife that slices through the earth/ without the earth's knowing,/ severs and joins at the same instant.' The speaker cannot cross over because his desire, being based on fantasy, cannot be fulfilled. The border 'runs inconspicuously through modest households,/ creating wry humour—whole families/ eat under one flag, shit under another,/ humming a different national tune.' Refusing to accept one side or another, the speaker lies down on the border.

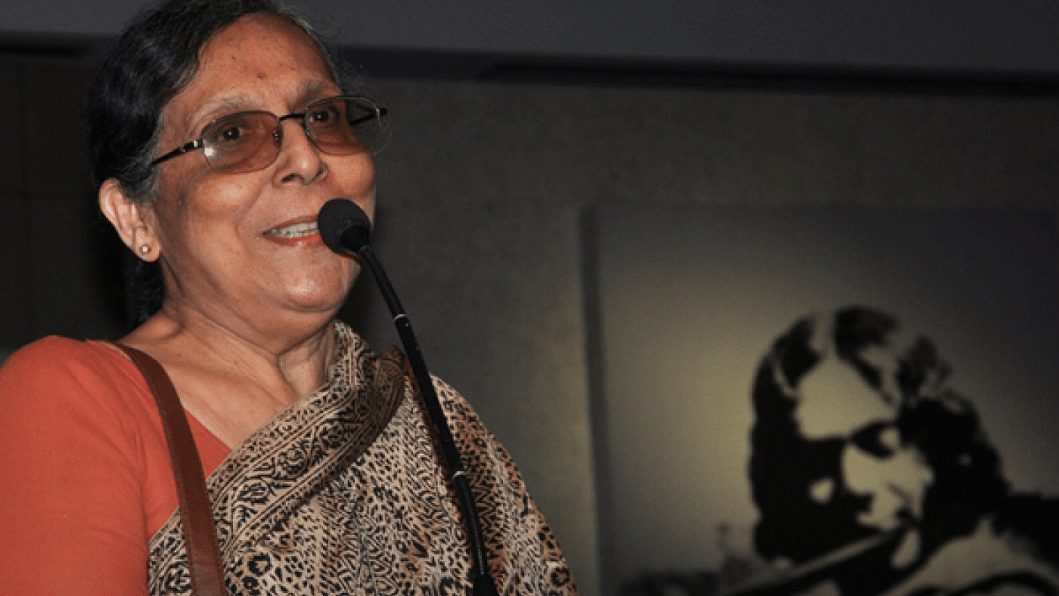

Last year Lexington Books, USA, published Revisiting India's Partition: New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics, edited by Amritjit Singh, Naini Iyer, and Rahul K Gairola; it includes two essays by Bangladeshis, Md Rezaul Haque (on 'The Case of Hasan Azizul Huq.) and myself ('Partition and the Bangladeshi Literary Response', from which the present piece is adapted.) The seventieth anniversary of Partition will witness the publication of an anthology, Looking Back: India's Partition Seventy Years On, edited by Debjani Sengupta, Tarun K. Saint and Rakshanda jalil, and published by Orient Black Swan; it includes a story in translation by Selina Hossain and one of my poems, 'Grishma, Barsha'.

Bangladesh's Partition literature deserves to be considered alongside similar works from other parts of the subcontinent. But more important than literary criticism is the task of transcending the conflicts that have given rise to the literature. Perhaps the most deleterious outcome of Partition has been the partitioning of the subcontinental mind. We have not only become an extended family of squabbling nations, we have grown to deny our civilisational unity. It is imperative that we make efforts to rediscover our commonality. This is true in every realm of experience, the cultural as well as the socio-economic and political. We cannot go back to the status quo ante, we cannot undo a tragedy, but we can try to go beyond towards a better order of things. Dealing critically with the cultural fallout of Partition is a necessary first step in that endeavour.

Kaiser Haq is a poet, translator, essayist, critic and academic.

Comments