In conversation with Ayesha Jalal

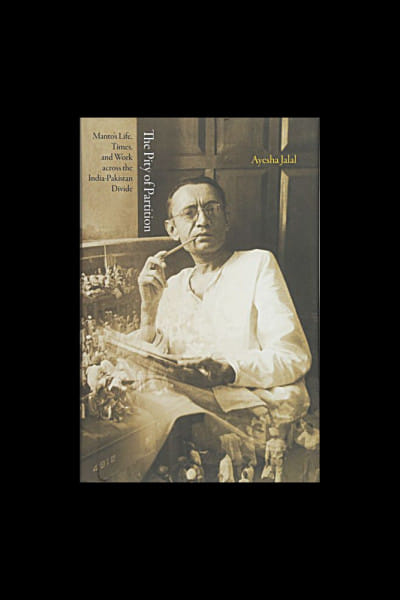

Historian Ayesha Jalal, the Mary Richardson Professor of History and Director of the Centre for South Asian and Indian Ocean Studies at Tufts University, is one the most prominent partition scholars, whose work has provided new insights and perspectives on the history of the partition of the Indian subcontinent. Her work has focused on the circumstances and roles of individuals which resulted in the creation of Pakistan, especially in her acclaimed book, The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the Demand for Pakistan (Cambridge: Cambridge U Press, 1985). Other books by her include a study of her grand-uncle, acclaimed writer Saadat Hasan Manto, titled The Pity of Partition: Manto's Life, Times, and Work Across the India-Pakistan Divide (Princeton University Press, 2013), and The Struggle for Pakistan: A Muslim Homeland and Global Politics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014).

The Star Weekend interviewed Professor Jalal over email about her work and insights on the 70th anniversary of the partition.

Do you think the partition was inevitable?

Inevitability assumes that something was unavoidable, regardless of human responsibility and actions. Apart from being untrue in the case of India's partition, this is entirely contrary to a historian's way of thinking, where attention invariably focuses on the domain of political contingency and the choices made by human beings.

The partition of India was effectively the partition of the two main Muslim-majority provinces, Punjab and Bengal. There was nothing inevitable or pre-determined about this. Until the bitter end, Mohammad Ali Jinnah insisted that it was wrong to equate the principle of Pakistan with the partition of Punjab and Bengal. The prospect of a united and independent Bengal remained a possibility and was scotched only because the Congress High Command was averse to the idea of a united Bengal outside the Indian union. Jinnah by contrast, supported a united and independent Bengal, ruefully noting that Bengal without Calcutta was like asking a man to live without his heart. Even in the case of Punjab, a partition of the province was opposed by a cross-section of Muslims. Under the provisions of the June 3 partition plan, a vote of the non-Muslim members of the assembly from the non-Muslim majority districts sealed the fate of both Punjab and Bengal in the face of opposition from those representing the Muslim-majority districts.

" As the founding myth of the post-colonial nation-states of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, partition is a way of seeing and being that separates what were once historically indivisible people, communities, and linguistic cultures into distinctive political entities.

How do you assess the two-nation theory?

Insofar as nations are imagined communities, the two-nation theory was based on a subjective belief in the right of Muslims, regardless of their internal divisions, to acquire a substantial share of power in an independent India. Politically the 'two-nation' theory was deployed by Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the All-India Muslim League as a political tactic aimed at claiming parity with Hindus at the all-India level. Partition as it came about in 1947 was not only a political abortion of the two-nation theory, but led to the creation of two separate nation-states—Pakistan, which emerged as the largest Muslim state in the world at the time, and predominantly Hindu India containing the largest Muslim minority. The creation of Bangladesh in 1971 split the Muslims of the subcontinent into three separate nation-states. Pakistan—the much vaunted homeland of British India's Muslims—today has fewer Muslims than India and Bangladesh put together. Such an eventful history of the two-nation theory underlines the extent to which there can be a sharp disjunction between the claims of nationhood and the actual achievements of statehood whenever and wherever there is a lack of a neat fit between identity and territory.

Based on your work, how do you think has the narrative of the partition evolved and impacted/continues to impact the politics of the subcontinent?

Partition is not just an event that occurred in 1947 but an ongoing process that continues to structure post-colonial South Asia. The decision to partition India snapped economic and social linkages forged over the millennia that had survived periods of imperial consolidation and political decentralisation, to create a loosely layered framework of inter-dependence that had to be constantly negotiated between diverse people living under the rule of sovereign or quasi-sovereign regional rulers. 200 years of British colonial rule buttressed by an imported idea of monolithic and indivisible sovereignty imposed an administrative centralisation on India's far-flung regions that never amounted to real political unity. It was Congress's eager embrace of the idea of non-negotiable and indivisible sovereignty that foiled Jinnah and the All-India Muslim League's efforts to win a large share of power for Muslims in an undivided and independent India.

As the founding myth of the post-colonial nation-states of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, partition is a way of seeing and being that separates what were once historically indivisible people, communities, and linguistic cultures into distinctive political entities. The unities invoked in the constructed national narrations of South Asian nation-states, however, cannot wish away the facts of history and geography. If there are innumerable slippages, elisions, and contestations in narratives about the great divide that took place 70 years ago, there are awkward silences about its constant, and often violent, everyday re-enactments in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

How do you relate the partition with the breaking up of Pakistan in 1971?

Both 1947 and 1971 ensued from the political failure to arrive at power-sharing arrangements that could have made drastic solutions like partition unnecessary. If the causes of partition in 1947 had been properly understood as a product of India's federal dilemmas, and not reduced to 'religion' alone, the policies of the post-colonial state of Pakistan may have been less insensitive to the needs and aspirations of the majority population in the eastern wing.

In your book on Saadat Hasan Manto, you portrayed him as one of the most representative figures of the partition, be it through his life or his work. Many of the issues he dealt with, such as communalism, still haunt South Asia. How would Manto react to the reality of post-partition India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

For Manto, the pity of partition was not that instead of one there were two separate nation-states in the subcontinent, India and Pakistan, but the fact that 'human beings in both countries were slaves, slaves of bigotry . . . slaves of religious passions, slaves of animal instincts and barbarity.' He would have deplored the lack of empathy felt by the people for one another. But his sharpest criticism would almost certainly have been reserved for the leaders of the three countries for failing to arrive at accommodations of their respective differences to meet the political, economic and environmental challenges facing the South Asian region as a whole.

Comments