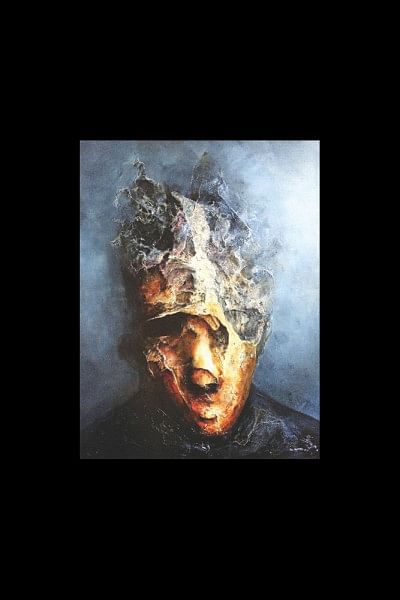

Inside a sadist's mind

"In the country that she came from, poised forever between the terror of war and the horror of peace, Worse Things kept happening."

-Arundhati Roy, The God of Small Things

Raped on a bus, killed and thrown off on the street. Raped on Eid. Raped at a party. Head shaved by family members after rape. We read, we vent, we discuss, we forget, we are reminded again the next day. And worse things keep happening.

Much of the conversation revolves around what happened to the victim, where she was, what she was doing, whether she was alone, whether she was with a friend, what she was wearing, what economic background she was from and the list goes on. By the end of the week we would have a detailed character sketch of the victim and nothing about the perpetrator.

Maybe we engage in such thorough analysis of the victim's life and character because it helps us understand that this can happen to anyone, not a certain kind of woman, or person. But the problem with this conversation is that it leaves out a very important aspect. It fails to ask the question: Who rapes and why?

Umme Kawsar Lata is a lecturer and assistant educational psychologist at the Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology of Dhaka University. Lata received her MS in education psychology from Dhaka University and diploma in counselling from India and has been engaged in various volunteer activities for at least five years now. I sat down with her one Thursday evening, primarily because I was perplexed.

I wanted to explore why people rape instead of why people get raped; why the relatives of the rapist feel the need to shave the heads of the victim to further shame her instead of holding the rapist accountable; why people feel entitled to raping people at parties; why people feel entitled to attacking someone's body because she is on a public transport; what psychological factors play a role in perpetuating rape and the rapist mindset.

But also, I was tired. I needed some help and some hope. I needed some reassurance that not every man on the street is a rapist.

So, we sit at a cafe in Dhanmondi, as the sun sets, and I ask Lata, "Tell me, you've studied this. What are some psychological factors that motivate violence?"

"Some people are sadists. Sadism, like any other disorder, is an illness. In some people, you can detect a pervasive pattern of cruel, demeaning, and aggressive behaviour, beginning by early adulthood, or even childhood. But even if you are predisposed to violence, you will need some form of a trigger. Sexual sadism is a subset of sadism, where one derives sexual pleasure from inflicting pain upon others."

"But," I interrupted, "there is a problem with that narrative, no? I mean, are all sexual assault perpetrators, necessarily sadistic? Also by talking about gender-based violence as something that is perpetuated by a mental illness, we risk stigmatising mental illnesses. In gender theory, we talk about gender as a social construct. 'Gender-based violence' and 'violence against women' are terms that are often used interchangeably as most gender-based violence is inflicted by men on women and girls. But the 'gender-based' aspect of the concept is retained as this highlights the fact that violence against women is an expression of power inequalities between women and men. So, we see violence primarily as a result of uneven power dynamics, which makes it a social problem rather than an individual's problem."

"Well, that's what I mean by trigger. Sadism can be triggered by a number of factors, social, personal, etc. Any disorder, in order to be activated, needs a trigger. Even if I have a certain kind of natural disposition, I don't necessarily need to turn into a violent person." she said.

"So then, unlike say schizophrenia, sadism isn't genetic?"

Lata shakes her head.

"There's no research that I know of that confirms that it is. In fact, I think the difference between an illness like schizophrenia, for instance, and sadism is that sadism is mostly learned behaviour. Those of us who study educational and counselling psychology focus much of our education on learning theories as conceptual frameworks describing how knowledge is absorbed, processed, and retained during learning. Cognitive, emotional, and environmental influences, as well as prior experience, all play a part in how understanding, or a worldview, is acquired or changed and knowledge and skills retained.

The social learning theory of Albert Bandhura identifies two ways in which individuals learn. Firstly, through modelling so you see things happen around you and you learn. For example, if a child grows up in an abusive household, he will learn to normalise abuse and violence. And secondly, through trial and error, where learning occurs through tentatively trying various responses and discarding some until a solution is attained. But for learning to occur, the learner must be definitely motivated."

I contemplate that with furrowed brows.

On one hand you may normalise violence if you are regularly exposed to it. On the other hand, there is a culture of impunity when it comes to sexual violence, a "boys will be boys" narrative that enables men to get away with what they are doing, because nobody holds them accountable for their actions. What does that mean for someone with a sadistic personality?

In 1984, John Oldham MD began work on a personality system for normally healthy people based on the neurotic categories of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, referred to in shorthand as DSM. Sadism was previously considered as a disorder in an appendix of the DSM.

According to the DSM those who demonstrate sadistic tendencies are usually of the 'Aggressive' personality style which is characterised by Command which means they take charge, and Hierarchy, which means they operate within traditional power structures and Guts.

If I were to map a rapist's psychological journey then, in order to understand why they would rape, it would need to start with an acknowledgement of the fact that he is looking to exert authority and power over the victim's body. A systemic empowerment that promotes the male gender over other genders, i.e. patriarchy, then perpetuates a kind of hierarchy that is his comfort zone. And finally, a legal and social system that fails to hold rapists accountable gives him the guts to face difficult and dangerous situations without being distracted by fear or horror.

So, regardless of whether the rapist is learning through modelling because of exposure to violence at home, on television, on social media, on the streets, or through trial and error where society allows him to get away with smaller acts of violence until something bigger happens, we have created a system that enables him. So he does what he does, gets away with it, repeats.

And Worse Things keep happening.

Shagufe Hossain is founder and project director of Leaping Boundaries and a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments