Re-thinking 'Poverty' in Bangladesh

When the war ended in 1971, Bangladesh had gone through two of the worst disasters in the history of the modern world. The first came in the form of Tropical Storm Nora, which resulted in widespread destruction and death around the coastal areas of the country. By no means was Nora the strongest or most violent storm that ever hit the edge of the subcontinent, but the devastation it left in its wake was massive. Winds at Chittagong were recorded at around 144 km/h and storm surges as high as 10 metres hit the coast and the surrounding farm areas. But the disaster was as much a result of policy and response, as it was of the storm. The then East Pakistan government did little to mobilise information or resources to shelter the vulnerable, and estimates of the death toll ranged from 300,000 to 500,000. The next year saw the country fall into a civil war which eventually led to secession and the formation of Bangladesh. But not before the region witnessed a genocide instigated by the defeated Pakistani army, which systematically crippled the entirety of an already impoverished region.

It's an understatement that the challenges facing the governments to come were massive. In the new country, there were only 300 gasoline pumps, 20,000 private cars and 5,000 buses. But that was far from the real concern. 80 percent of the population was illiterate and according to UN estimates, 78 percent of the population lived in absolute poverty (meaning their daily intake of food was less than 90 percent of the minimum requirement needed to get through the day). In a country where more than three-fourths of the population did not have enough to eat, it was a case of poverty and not simply inequality. It wasn't just a case of some people having more than others—there were just not enough resources to go around at all. The international response to this was the pouring-in of aid agencies; the government seemed content to take the back seat and let civil society clean up the mess. 46 years down the line, the story is no longer the same. The country is no longer in the abject situation it found itself all those years ago. Several factors contributed to this improvement, and influential among these were state and NGO-led interventions. Because (and often, in spite) of these factors, the country has pulled itself out of a hopeless situation and has been able to experience relative stability through the years.

Poverty alleviation and its myriad backers often take various avenues to solve a deep-rooted problem. The situation in Bangladesh led to it becoming the hotbed for social experimentation and many new techniques originated out of this region. Not least among them are the microcredit schemes—developed by Grameen Bank and BRAC—which went on to become a global phenomenon. It isn't the point of this article to go into the failings and successes of microcredit or other poverty alleviation programmes in the country. Indeed, such a discussion would and already has gone on for a whole library worth of books and research papers. Instead, we would like to focus on something which seldom makes its way into discourse when talking about poverty or the poor, be it in state-run circles or the nexus of local and international NGOs—income inequality. Many economists will point to the fact that income inequality was less of a problem than the extreme poverty that Bangladesh faced in the first three decades of its existence—and there will be a lot of truth to their statements. However, given that we have developed a somewhat sturdier infrastructure across the country, it is important that we begin to look at this problem more seriously, not just in Bangladesh but also in other countries who are in the throes of 'development' in the 'third world', where income inequality is that thing which isn't to be spoken of other than in socialist and communist circles.

In order to initiate this discourse, Centre for Bangladesh Studies (CBS) published a research report examining the trend of income inequality in the country since its inception. The findings shed a light on the ways in which this particular problem has been ignored (or actively kept out of the spotlight) over the last 46 years—to the point where it is quickly becoming one of the biggest challenges facing Bangladesh. At a time where the state refuses to be accountable to democracy and many other social freedoms, income inequality seems to highlight the trend of Bangladesh becoming a country ruled by the rich, for the rich.

Alarming trend

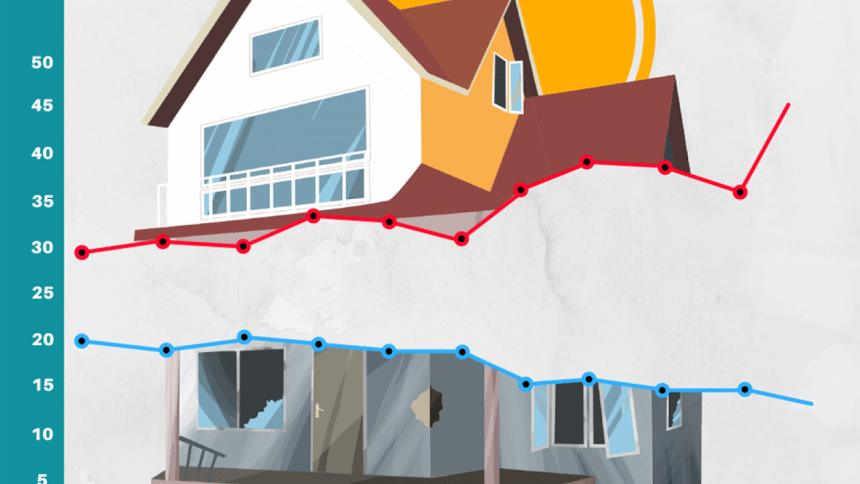

Along with the data on shares of total income, the research used an indicator called the Palma indicator which measures the share of income going to the top 10 percent of households divided by the share of income going to the bottom 40 percent of households. When the ratio is too high, it shows that the country is deeply unequal. The Palma data presented in the research shows that Bangladesh has seen its level of inequality rise over the past decade-and-a-half. The Palma has gone up from 2.62 in 2005 to 3.45 in 2015. The ratio dropped to 2.5 in 2010 before rising again. This shows that there has been a rising concentration of wealth in the top 10 percent of income earners in the country. Worryingly, this trend has been increasing over time and there has been a continuous accumulation of income in the top 10 percent of income earning households since Bangladesh's independence. Since 1973, an additional 17.8 percent of gross national income (GNI) has been accumulating in the top 10 percent. This is in stark contrast to the plight of the bottom 40 percent of income-earning households, which have seen their share of income deplete since independence. There has been an approximate transfer of 4.9 percent of income share away from the bottom 40 percent over the past 46 years. While the income share of the bottom 40 percent of households has decreased at a rate of 0.64 percent every year, the income share of the top 10 percent of households has been increasing at a rate of 1.49 percent during that time. In 2015, the gross average monthly income of the top 10 percent was BDT 1,47,388 while the average monthly income of the bottom 40 percent hung at BDT 10,657 only.

Since the liberation of Bangladesh, the bottom 80 percent of households has actually experienced a decrease in terms of their share of national income per household. This fact becomes even more worrying when we consider that the country has not seen a sustained period of income redistribution since its inception. And so, the goal of moving from low-middle income to middle-income status would not lead to any meaningful redistribution or equitable distribution of income or wealth. The Palma ratio also has many implications regarding the nature of the development that is currently being undertaken in Bangladesh. We can safely conclude that since its inception in 1971, the country has failed to establish any sort of equitable or redistributive economic system. In fact, all the numbers point to the fact that it has progressively gotten worse.

Problematising poverty

Poverty has a certain accepted definition under the UN framework, as does the eradication of poverty. However, if there is a substantial decrease in the percentage income share of the poorest households over time then poverty eradication becomes a deceitful platform. It is counter-intuitive to speak of poverty eradication without acknowledging income inequality and the real socio-economic divide between the bottom 40 percent of the household population and the top 10 percent. In short, we believe that state policies have been ineffective in tackling income inequality and that any redistributive agenda that subsequent governments have had in Bangladesh have all failed. That is why any discussion on Bangladesh's developmental and economic history must include the fact that over time income and wealth has been appropriated from the bottom sections of society to the top. Here, again, we are often misled by numbers. The World Bank defines extreme poverty as living on USD 1.90 per day (at US purchasing power) and moderate poverty as less than USD 3.10 a day. It is possible to have an entire nation earning more than that mark but it would not translate to a fair or equitable society if the gap between the rich and poor is still very large.

And so, we can return once again to the two years of 1970 and 1971 which forever changed the context of the lives of people living in this region. But with each disaster there comes a new disaster economy that creates a nexus between all the stakeholders and those interested outsiders who come together to re-fashion or re-store normal order. These economies and their global linkages are complex and once embedded into the social fabric of a region are difficult to unentangle. Some of the programmes that were rolled out by both state and civil society were integral to the survival of the people post-hurricane and post-war. But the context of our realities have altered greatly and it is no longer enough to feel successful if everyone has enough to eat. There are larger needs—education, equal access, better lifestyles and a better environment. To that effect, income inequality is a much more useful marker for the context of our times than the political economy of the policies surrounding 'poverty'.

Any policy tackling income inequality, however, cannot be engaged with, much less implemented, without acknowledging the elephant in the room—the state. At the heart of it, any serious challenge to inequality must critically examine the role of the state in perpetuating inequality.

The full report can be found at www.cbsbd.org.

Ahmad Ibrahim is a research fellow at Center For Bangladesh Studies (CBS).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments