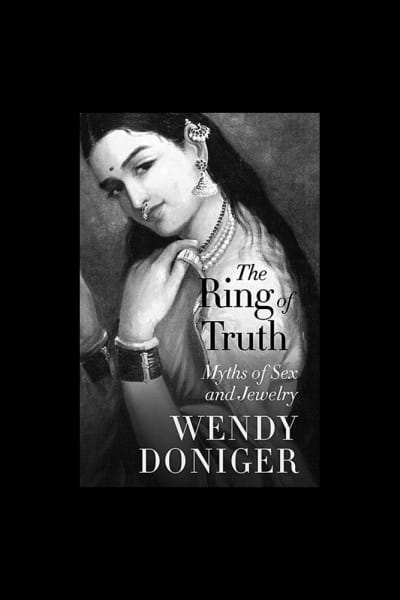

The Ring of Truth: Myths of Sex and Jewelry

"I started collecting stories and ideas about rings over the years... Over these years, wherever I went, no matter what people asked me to talk about, I talked about rings, and I took furious notes not only in the Q & A but during the lecture itself, as the adrenaline generated new ideas even while I was telling the audience the old ones."

As she acknowledges it thus at the beginning of her new book, Wendy Doniger offers a riveting cross-cultural history of jewelry and its role in seduction, romance and infidelity -- ideas that she had been researching and accumulating for a long period of time. Basically the book is about the stories that other people have told, through recorded history and all over the world, about pieces of circular jewelry, particularly rings. Providing accessibly written retellings of countless stories from mythology, folklore and literature, she gives us stories that are each unique but are linked through a common cluster of meanings. The rings in this book always have some connection with love or sexuality.

Doniger begins her book by asking several questions and then tries to seek answers to those questions through different chapters and different constellation of stories. Why are sex and jewelry, particularly circular jewelry, particularly finger rings, so often connected? Why do rings keep getting into stories about marriage and adultery, love and betrayal, loss and recovery, identity and masquerade? What is the mythology that makes rings symbols of true (or, as the case maybe, untrue) love?

The first seven chapters are about rings throughout history; in particular, they are all recognition stories in which a ring is a vital clue. They deal with sexual rings (chapter 1), rings found in fish and found (with children) in the ocean (chapter 2), rings of forgetful husbands (chapters 3, 4, and 5) and of clever wives (chapters 6 and 7). Chapters 1 and 2 are broadly cross-cultural (though largely Anglophone) and deal with a number of relatively short texts; the next three chapters concentrate on fewer stories discussed in greater depths, taken from individual cultures: India (chapter 3), medieval Europe (chapter 4), and the Germanic world (chapter 5). Chapters 6 and 7 deal with a single theme – the "clever wife" – in cross-cultural distribution. Chapters 8 and 9 veer ever so slightly into stories about necklaces in particular cultures and particular historical periods: a treacherous royal necklace in eighteenth-century France (chapter 8) and true-and-false necklaces in nineteenth century English novels and twentieth century American films (chapter 9). The final two chapters return to rings, to the invention of the myth of diamond engagement rings in twentieth century America (chapter 10) and a concluding consideration of the cash value of rings and the clash between reason and convention in myths about rings of recognition throughout the world (chapter 11).

Some of the rings in the stories that we encounter throughout this book originally belong to men, and just about all the jewelry that women have, they get from men (sometimes they inherit it from their mothers, but not often). But both men and women tell the stories, though men are usually the attributed authors of the earlier texts. These stories drive Doniger's arguments about six basic points, three about the content of the plots and three about the function of the narratives. Firstly, most of the stories take for granted what Doniger calls the "slut assumption" that women get jewels only from men they sleep with (husbands or lovers). Secondly, women use jewelry to their advantage in the stories, often to win (or win back) their husbands, while men use (or try to use) rings to wriggle out of promises to women. Thirdly, men's concern for the paternity of their children, and women's for their children's legitimacy, drive many of the myths of rings of recognition.

As far as the function of the narratives are concerned Doniger states that by overcoming reason, the myths allow us to believe what we want to believe about the power and endurance of sexual love and about our ability to rebalance the moral world. Also, the tension between hard evidence ("reason") and the soft power of myth ("rationality") experienced by an audience is mirrored by a similar tension in the stories themselves. Finally, different versions (or variants, or tellings) of much-retold stories supply us with a cumulative mass of different psychological details that together suggest deeper meanings of the myth. And comparing earlier and later variants allows us to see myths in the making, a process that we can then recognize in such contemporary examples as the invented tradition of diamond engagement rings.

The book therefore does not move in a linear fashion but expands outwards, as if from a prism. Thus we get to read about ancient Sanskrit myths, Celtic lore, fairy tales, literature, modern song lyrics, all of which depict detours of love, adultery and the foibles of jealous husbands and clever wives. One is surprised at the ease with which Doniger leaps easily from Sanskrit fables to Roman ones, from medieval lore to the 18th century French court and modern Doris Day movies. She brings together Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Seigfried, Shakuntala and Marie Antoniette, Solomon and Shakespeare and many, many others with ease and lucidity.

Indeed, the ease with which Doniger traverses different ages and cultures is truly mindboggling. Summarizing it in one sentence, one can say that this book offers a thoroughly interdisciplinary cross-cultural history of jewelry. The jewelry in the stories that she has collected here preserves (and sometimes erases) true and false memories and of promises that often come true and sometimes lie.

Like all of Doniger's other books, The Ring of Truth, is an astonishing and hugely satisfying work of scholarship rendered in compulsively readable prose. The Indian edition of this book has on its cover a painting by Raja Ravi Verma entitled 'A Lady Holding a Fruit,' thereby adding considerbly to the charm and the significance of the title.

Somdatta Mandal is Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments