Seizing the opportunity?

Three years ago, a Bangladeshi woman, let's call her Nila, petitioned the High Court asking for protection of her fundamental right to equality. She had been living in a violent marriage. But as a Hindu in Bangladesh, she has no right to divorce, and no exit route from continuing abuse. She asked the Court to give her the same rights to escape a violent marriage that are available to the millions of other Bangladeshi women who marry under customary or religious or civil law.

The Court accepted her petition and asked the government to explain why the lack of divorce rights under law for Hindu women should not be considered as discrimination. Later, on considering the importance of the issue, it asked four senior lawyers to assist it with relevant arguments and legal submissions as 'friends of the court'. It also sought the views of two Hindu religious scholars and two rights organisations, Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) and Manusher Jonno Foundation (MJF), to obtain information on 'the prohibition of divorce of Hindu women'.

Months passed. As often happens, the judge concerned was allotted different issues to adjudicate, and the case no longer appeared on any of the daily cause lists. In the meantime, Nila's husband filed papers in Court claiming that he had already divorced her under customary law. Perhaps exhausted by the prospect of years awaiting a resolution of the larger constitutional questions, Nila filed a petition saying she would not pursue her constitutional challenge. On the basis of her petition, the Court disposed of the matter.

But the larger question—about whether Bangladeshi citizens, and women in particular, are entitled to equality and freedom from discrimination based on religion and gender—remains unresolved.

In Bangladesh, today, 46 years after our Constitution was adopted promising us equality, there is no single law on marriage or divorce. While there is a possibility to marry under a civil law, very few people in fact choose this option, and most people in Bangladesh marry under their respective personal laws.

So a Muslim woman has a right to divorce if it is clearly stipulated in writing at the time of her marriage, and may exercise this in cases of incompatibility, lack of maintenance, cruelty or for any reason stated. And of course she can be divorced at any time and unilaterally by her husband. A woman, who marries under Christian law, or civil law, can also initiate a divorce if she can establish cruelty or some other cause. Her husband can divorce her simply upon establishing cruelty. But under Hindu law, there is no right to divorce—for either men or women—with exceptions 'under customary law for certain lower castes'. In other words, women have fewer rights than men to divorce, and Hindu women not only have fewer rights than men, but also fewer rights than women of other religions. In all these years there has been no reform of marriage and divorce laws for Hindus, or for any community other than Muslims. As far as I'm aware, our Parliament has never debated these issues, and no MP has raised a question about this continuing inequality. The Law Commission of Bangladesh, to its credit, has engaged in some consultations on personal law reform, but it is unclear whether or how it has taken this process forward.

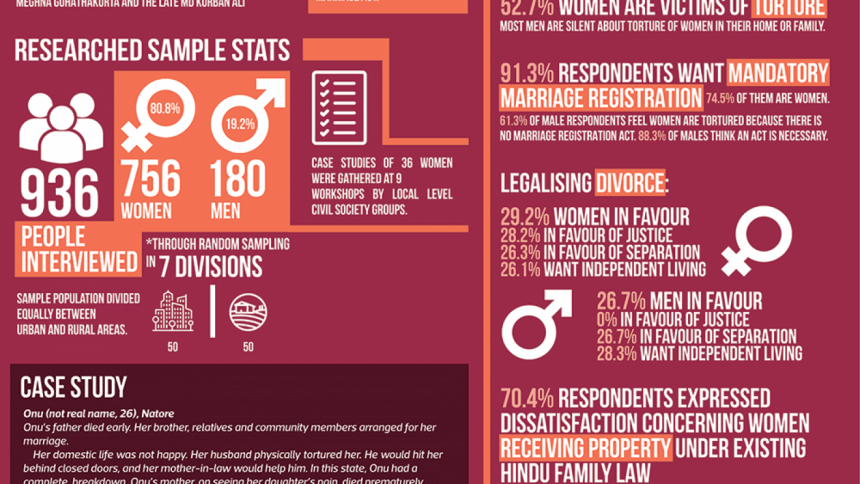

The deafening silence of our law and policy makers has been pierced from time to time, though with little response sadly, by rights organisations. Notable examples include the preparation and submission of a draft civil code by the Bangladesh Mahila Parishad to the Ministry of Law, and repeated calls for reform and for adoption of civil laws by groups such as Naripokkho, Bangladesh Nari Progati Sangha, Ain o Salish Kendra and others. Researchers have also highlighted the issue, for example the detailed report for the Manusher Jonno Foundation by Dr Meghna Guhathakurta, now a Member of the National Human Rights Commission.

At BLAST, given the opportunity to assist the Court, we sought to add our voices to this muted if robust chorus. We prepared a review of the relevant laws across South Asia. We were given assistance pro bono by lawyers from a number of the countries, through the Trust Law network. We found that of all the SAARC countries, only Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, have laws in place that allow Hindu women to divorce. Pakistan's law was adopted only a few months ago. This means that a Hindu woman in Bangladesh in fact not only has fewer marriage rights—to equality and to freedom from family violence—than other Bangladeshi women, but also women in other South Asian countries.

Given that Bangladesh is so far ahead of our neighbours in achievement of so many socio-economic indicators on gender equality, why are we lagging so far behind in ensuring formal legal equality for women? Is it simply that no one in power is interested in hearing the voices of Hindu women, particularly those who are powerless and living trapped inside a violent and abusive marriage, with no access to remedy or support?

Do we know anything about what Hindu women want? Dr Meghna Guhathakurta, in her research, spoke to Hindu men and women around the country about precisely this question. She found that 30 percent of her respondents, men and women alike, wanted to see Hindu laws reformed to recognise the right to divorce. The reasons they identified are very similar to those that were articulated by India's BN Rau Committee in 1955 when recommending reform of Hindu personal laws. When countering the criticism of reforms put forward by orthodox members of the Hindu community, that marriage is sacrament and indissoluble, they noted that this view would prevent a Hindu widow from re-marrying, but widow re-marriage had been legalised almost a century earlier. They also commented that Hindu women were being left in limbo, abandoned by husbands, but unable to re-marry or continue with their right to family life. They found that divorce was already practiced as a custom in many Hindu communities, but because of lack of codification, and given the levels of literacy, many people simply did not know about these rights.

The comments of the BN Rau Committee are all too pertinent today, more than 60 years on.

It is more than a little painful to see that we are lagging behind all other South Asian countries. I hope before another year passes, we might begin the process of reforms. The struggle for freedom must also be about freedom to chart the course of our own lives. The hearing that concluded in Court today may be the beginning of this process. Thank you Nila for starting the discussion.

Sara Hossain is a lawyer at the Supreme Court of Bangladesh and an honorary executive director of BLAST.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments