The Partition of Bengal, 1905: South Asia's first Look East Policy?

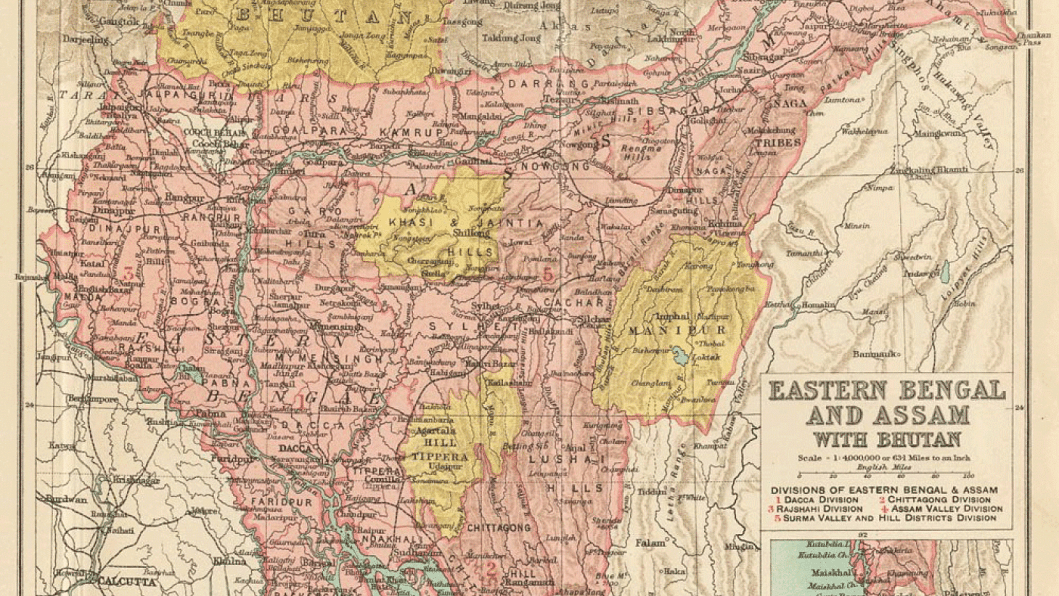

The creation of the province of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905, through the partitioning of Bengal on October 16, is one of the most significant events in the history of modern Bangladesh. The new province, with its capital in Dhaka was however short-lived and was annulled six years later due to strong resistance from the Kolkata-based political and economic elite and a bulk of the middle class. In fact, this event ignited a half-awakened Indian nation and ever since, the historical episode is perceived as a communally motivated divide-and-rule ploy of the empire. But new researches suggest that the making of the new province may also well be regarded as the first "Look East Policy of South Asia".

The imperial gaze east of Kolkata was boosted by an emerging set of issues visible by the early nineteenth century. The financial losses of the East India Company arising from the decline of the textile industry in India and the cost of the inflexibility of the permanently settled revenue system were becoming all too clear. Financial constraints demanded that the city of Dhaka regain the capacity to generate revenue, resulting in renewed interest in the revival of the city as a new, geographically suited commercial hub. Charles D'Oyly's (1830) poignant sketches of Dhaka's environment and architectural relics evoked nostalgic memories of it as a Mughal metropolis.

The book that contained the code of Dhaka's revival came from James Taylor (1840), published at a time when global trade and commerce were increasing. It emphasised the fact that Dhaka was not faring as it used to in terms of trade, demography, and social mobility. In the decades that followed early imperial concerns for Dhaka, the city's slow but steady regeneration was observed.

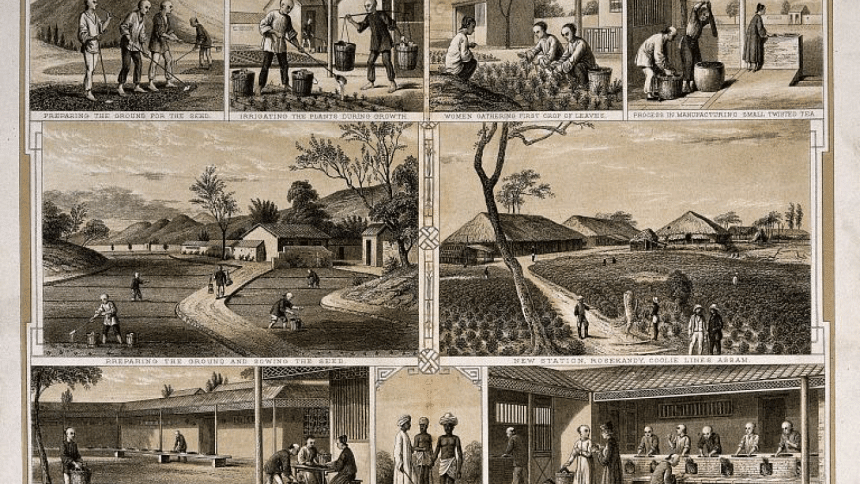

If by the second half of the nineteenth century Dhaka's geographical and agro-ecological locations made it a fitting outlet to the Indian Ocean, other developments took the imperial gaze further east. The north-eastern borders of India were subject to geological investigations for minerals as early as the turn of the nineteenth century, but it was tea in Assam that practically pushed the empire to the next spatial horizon. As jute of Eastern Bengal and tea of Assam were visible items in the imperial bazaars, Chittagong port began to catch up with Kolkata port. The spatial triangle of Dhaka, Assam, and Chittagong made more sense on account of some developments that were informed by the lure of further east towards south-eastern Asia and south-western China.

One of the two lines of communication from India to China being considered ran from Chittagong towards Yunnan via Bhamo and the other across the Shan states.

"If the empire looked to a larger spatial domain of mobility of humans, commodities, and ideas, the Kolkata-based Bengali national imagination settled on a boundary that made little sense beyond a more inward lore of the agrarian. Politics, patriotism, and palliatives for economic woes—all expressed themselves centrally in terms of the land and landscape of Bengal.

By the 1860s, the British were increasingly uncomfortable with the greater presence of other imperial powers, especially the United States in Shanghai and other Yangtze delta regions. Therefore, the idea of pre-emptive efforts to get to the Yangtze valley through what became known as the Irrawaddy Corridor emerged. Edward Sladen, the British political agent at the court of the last Burmese King in Mandalay, was particularly worried that the Americans were soon going to take control of trade along China's eastern coast. He suggested that the British should find a western doorway to China. He felt that a route to China through Burma would be of "highest importance".

In its 1899 conference, the Associated Chambers of Commerce, represented by over seventy chambers of commerce in Britain, recommended that, under the vigorous railway administration of Lord Curzon, Chittagong should be connected with Kolkata in the west and the Mandalay-Rangoon Railway in the east. It felt strongly about this, as Russia had got hold of Taiwan, and France, after taking control of Tonkin, was pushing forward a railway line to Yunnan. By 1904, the British Indian government reached an agreement to construct a number of routes from Burma to China on behalf of the consul-general in Yunnan.

North-eastern India's trade link with China and Myanmar became visible in the context of certain other developments in Dibrugarh near the Assam-Myanmar borders in the Brahmaputra valley. Curzon, as it appears, arrived in India at a time of great trans-regional thrust across its north-eastern borders. He soon took initiatives to justify the constitution of the new province through spatially specific arguments. In his speech in Dhaka, which was part of his publicity trip to Eastern Bengal immediately before the formation of the new province, Curzon referred to the commercial enterprises of Eastern Bengal during the Muslim rule and argued that the new province must "develop local interests and trade to a degree that is impossible so long as you remain, to your own words, the appendage of another administration." He felt that such development around Dhaka "would go far to revive the traditions which the historical students assure us once attached to the Kingdom of Eastern Bengal" (Curzon 1903–5). This and other similar statements patronising Bengali Muslims by the lesser officials of Curzon, to date, remain the master clue to the imperial machination to weaken Indian nationalism through fuelling communal politics.

The Curzon administration's multiple languages of public engagement, such as the liberal overtone of labour relations in Assam, the demographic reshuffling in Myanmar, the Muslim communitarian revival in Dhaka, and a racial trajectory in Mymensingh and Assam, were drawn together to rehearse a policy to suit a manageable spatial arrangement in the form of a new province, which was clearly focused on Southeast Asia and south-western China along with the Indian Ocean rim that connected these regions. Yet, it was the imperial point of departure in Eastern Bengal rather than its expanding trans-regional terrain of exploitation beyond the border of India that raised the nation's wrath.

If the empire looked to a larger spatial domain of mobility of humans, commodities, and ideas, the Kolkata-based Bengali national imagination settled on a boundary that made little sense beyond a more inward lore of the agrarian. Politics, patriotism, and palliatives for economic woes—all expressed themselves centrally in terms of the land and landscape of Bengal. The new province therefore fell apart and Bengal reunited. But as moments of decolonisation approached, the diminishing interest in the trans-regional possibility allowed the communalised political strategies to execute a partition of Bengal and Assam, giving birth to East Pakistan, which emerged as Bangladesh in 1971. During the Cold War, these arbitrarily demarcated borders along India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar were further tightened, although cross-border infiltration of goods and humans continued. Starting in the 1990s, and more so since the recent opening-up of Myanmar, respective governments have attempted to revive the connectivity that existed in pre-national times across the borders of Yunnan, Myanmar, Assam, and Bangladesh. To promote trade, investment, and tourism, rails and highways are being planned, while deep sea ports along the Indian Ocean rim of the Bay of Bengal and South China Sea have been mulled.

Iftekhar Iqbal is a historian at the University of Dhaka and is currently based at the Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Brunei. He is the author of The Bengal Delta: Ecology, State and Social Change, 1840-1943 (Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

[This article is based on the author's "The Space between Nation and Empire: The Making and Unmaking of Eastern Bengal and Assam Province, 1905-1911", The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 74, no. 01, February 2015]

Comments