Thaler and the Nobel in Economics: A Vintage Selection

The neoclassical school was based on rationality. When making decisions, people maximise things they like and minimise things they don't like. Apparently, there's nothing wrong in this. It's based on Adam Smith's 'self-interest' and Jeremy Bentham's 'greatest happiness'. Economics soon transformed into a 'science' where human behaviour and decisions could be expressed through mathematical models. By the middle of the 20th century, economics had become the most mathematical of all the social sciences. Soon economists became advisors to governments. Policies were based on rationalism whichever side of the political spectrum the advisors belonged to.

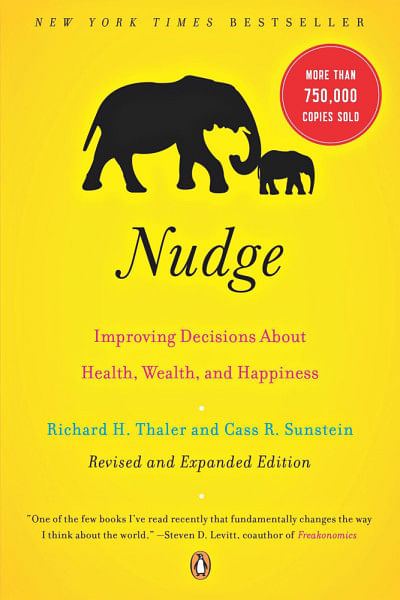

The challenge of rationality arises when applied to policy. The reasons are simple. Neoclassical economics assumes that the economic man or 'homo economicus' as John Stuart Mill termed, has the IQ of an Einstein; the memory of a microchip; and the patience and willpower of a Yogi. 'Normal' people can't calculate with full rationality. 'Normal' people don't always know what's best for them. Sometimes, 'normal' people need to be 'nudged' as Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein rightly said in their 2008 classic Nudge.

This year's Nobel in Economics went to Richard Thaler. Although Thaler wasn't the first to introduce behavioural economics, he did the most in convincing economists to 'think out of the box'. Slowly and gradually, governments started to pay attention to Thaler and other behavioural economists.

In modern societies, governments have an obligation to 'nudge' people to do things they normally wouldn't do. For instance, people aren't good at saving money for pension if left on their own to decide. This is a challenge for nations where credit cards and other distractions are ubiquitous. If people won't do what's best for them, then why not make it compulsory and 'nudge' them to save with contributions from the state, the employer and the person themself? If the individual decides not to save for pension they can opt out of the compulsory programme. This and other 'nudge' ideas soon caught the attention of policymakers. Small wonder that David Cameron was advocating 'nudge' ideas in his premiership election in 2010 and Barrack Obama in his 2008 presidential election.

Something powerful usually has a dark side to it. If individuals can be influenced to do things that they need to, they can also be influenced to do things they don't need to. When you go to a superstore, have you ever wondered why the chocolates are in the shelf within three feet from the ground? Do you see little children reaching out and making their parents buy? Now, does it make sense that pricey or promotion items are in the middle shelves where adults can see and pick? These and other ideas – good and bad – are what Richard Thaler and colleagues have introduced in behavioural economics.

Behavioural economics added a link to economics that was badly missing. The link was to see how people actually behave rather than think how they would behave. Richard Thaler has been one of the pioneers of this field in theory and also policy. It's not every year the Nobel Committee finds a vintage selection. This year they did. They awarded Richard Thaler for his contributions in making a 'dismal science' more human and humane.

Asrar Chowdhury teaches economic theory and game theory in the classroom. Outside he listens to music and BBC Radio; follows Test Cricket; and plays the flute. He can be reached at: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments