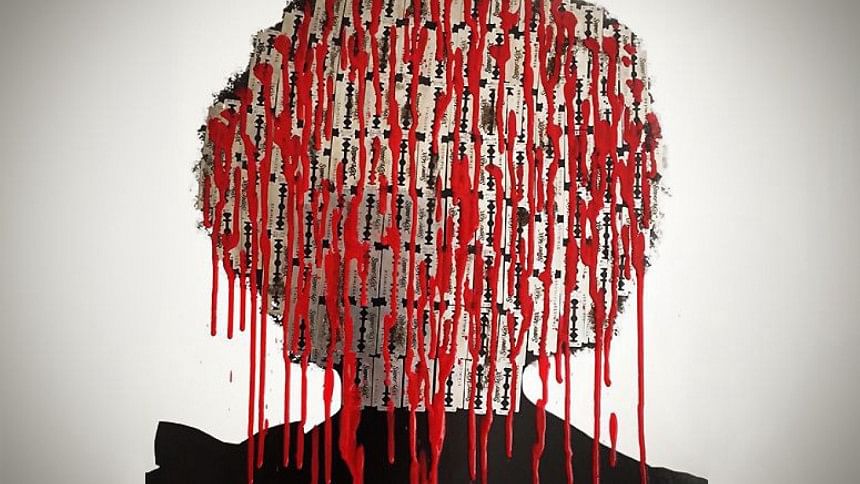

Female Genital Mutilation

The practice of excision is on the decline in Senegal, thanks to the mobilisation of victims and NGOs In Senegal, the law that penalises excision doesn't hold the weight it could hold, as local customs continue to exert a strong influence. Ethnic groups in south-eastern Senegal, in Kolda, haven't yet abandoned this practice, which they consider a means of preserving the virginity of a girl, the honour of her family and that of the community. However, attitudes are slowly changing thanks to action taken by victims and by civil society.

It may be siesta time, but there's no rest for the girls of Bantaguel district in Kolda, South East Senegal. On this Wednesday in March at 3pm these young girls – one after another – are converging towards the home of Oumou Barry, former president of the local girls' club. The courtyard of her home is their headquarters. "We can say that instances of genital mutilation have declined. These young girls' clubs have contributed. It's not easy to convince the adults, who are attached to our ancestral practices", confides Barry. The law doesn't carry much weight compared to the strength of tradition. Certain ethnic groups have sanctified virginity. They practise excision because they consider it a way to preserve the virginity of their daughters, to honour the reputation of families and that of the community. For these communities, excision inhibits pre-nuptial sexual desire. "Our parents aren't well enough informed. They think that excision enables a girl to abstain from sexual relations until her marriage. Other families carry out what they call « closure » (Editor's Note – infibulation) which is reversed on the day that the girl leaves her family to join her husband. In our area, families are worried about the possibility of their daughters getting pregnant before marriage or losing their virginity", Oumou Awa Baldé explains. Furthermore, communities believe that excision purifies a girl or woman. Within her entourage, a girl or woman who has been excised is more respected than one who hasn't undergone this operation.

Gaining ground

At the offices of the NGO Tostan, located in the Nord Foire district of Dakar, the staff are not quite declaring victory yet, even after 20 years of awareness raising on the ground. On this Monday 28th August 2017, the founder and executive director of Tostan, American national Molly Melching radiates enthusiasm and passion for her work. "I want to make it clear, first of all, that it's the communities themselves that are deciding to give up the practice of excision. Tostan is only active in informing communities, and raising their awareness on human rights in a general way", Melching maintains. The practice persists. But attitudes are slowly changing. In Senegal, the time when those who spoke out about excision were vilified is now in the past. "We know that we haven't got a 100% discontinuation rate in the villages that have decided to turn their backs on this practice. But we have reached a real rate of around 70% abandonment", Melching says. The biggest gain for the movement has been religious leaders getting involved in awareness raising. Excision is not without its consequences on the health of those who undergo the procedure. "We have had cases of girls who have died from haemorrhages due to excision. Some women who were excised as girls suffer from difficulties when giving birth. Others are left with traumatism over the long term", Tostan's Senior Program Manager Penda Mbaye explains. These educators know very well that there is still a long road ahead. According to a 2016 annual report by the joint UNFPA-UNICEF Programme on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), today in the south of Senegal – which has the highest rate of excision when girls and women of all ages are considered - the prevalence of excision is at 47% among young girls, down from 77% among the age group above them a few years ago. In the north of the country, the prevalence of excision stands at 31% among young women aged 15 and above, and 22% among girls under 15 years. For Monitoring and Evaluation Manager Mady Cissé, the challenge is to enhance methods used to evaluate the abandonment of this practice within communities.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments