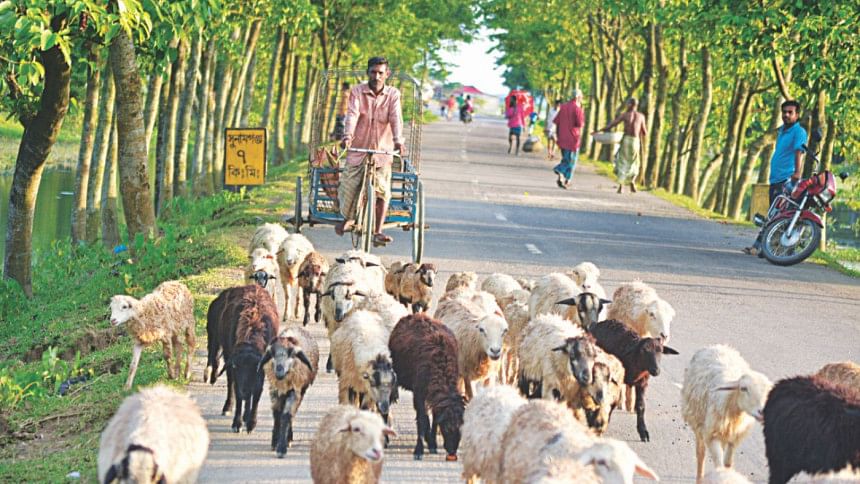

The miraculous journey of a sheep herder

Md Furkan Ali sits content on the bank of a field nearby, watching his 118-strong herd of sheep grazing idly on grass in the pastures.

Born to a poor family in the remote Tanguar Haor area of Sunamganj, going to school was a luxury far out of reach for him. He spent his early years next to his father, working as a day labourer in the fields, sometimes during harvest, at other times digging mud to prepare the fields for plantation.

Before long, he could not earn his living in Atkapara village of Sunamganj's Bishamvarpur upazila as the arable land either remained under water or too dry for farming.

Leaving his parents behind in a tiny thatched house on a haor embankment, Furkan travelled with a fellow neighbour around 122 kilometres east to Jaflong in Sylhet's Guainghat upazila to find work as a stonemason.

During afternoon breaks, he would stare in marvel at a huge, unattended flock of sheep grazing on the fields. Every day he wondered how these cattle were reared so casually. Once he met 50-year-old Mannan Mia, who owned a 30-ovine herd. Intrigued, Furkan began working part-time with him and slowly learned the tricks of the trade.

“Furkan was a quick learner. In a short time, he bought four lambs from me for Tk 5,100 to rear on his own,” said Mannan.

He worked at the farm for three years before moving back to his village home. He set up a small tin shed behind his house and bought 10 more lambs for Tk 10,000 to add to his ovine family of four.

At one stage, some of his sheep fell ill. It compelled him to seek out the local livestock officials for medicine and guidance. His sheep quickly regained health and officials began visiting him regularly to assist.

His ovine family slowly started to grow and he soon had to hire two people to help. He pays them about Tk 5,000 a month, along with a meal daily.

Ayesha Begum, his wife, said the fate of her family has changed since her husband began rearing sheep. He re-built the house, expanded the farm, and bore the education costs of their two children. The family is self-reliant now.

Initially, Furkan took his sheep to the local market and sold them for Tk 3,000-Tk 5,000 each, depending on the size. But he has now built such a rapport that wholesalers come to his doorsteps to buy his cattle.

Mizanur Rahman, who sells sheep at Sunamganj bazar, said people prefer to buy sheep as it is tastier and more nutritious, and costs Tk 200 a kilogram, which is cheaper than beef.

Belal Hosain, district livestock officer in Sunamganj, said sheep rearing is relatively risk-free. “We have given Furkan necessary training to nurture the animals.”

Furkan also sells sheep's wool, which has to be cut every two-three months, for Tk 200 a kg.

“Selling wool is a promising business, but I need to expand my farm to grow it."

There is a seasonal demand for wool which picks up ahead of winter, he added.

“I will be able to increase the production of wool as soon I get bank loans to expand the farm and employ more people.”

Officials said the effect of the ovine population on the economy will be perceptible when the production of wool would be sufficient to meet the demand of local industries.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments