The Final Sky

Dart-throwing chimpanzees predict wars and economic collapses almost as good as super-forecasters who predict events much better than chance. Some say, it's easy for an intellect to know all forces that set nature in motion and hence, if we were to submit data to analysis, then the future would be as clear as our past and we would be able to predict time. While an early nineteenth-century astronomer Laplace grew confident about this omniscient demon predicting tomorrows, in the twentieth century, an American meteorologist, Edward Lorenz, contradicted it by saying that while it was possible to know when exactly it would rain by watching the water vapour coalesce around the dust particles, it was impossible to know how a particular cloud would develop or the shape it would take. While Laplace's forecasting demon can predict tides, eclipses or the phases of the moon, Lorenz punctured predictability by presenting a hypothesis of a massive rock bumping Earth off its orbit around the sun.

While many life insurance companies continue being in business by predicting disability and death by analysing someone's age and profile, gender, income and lifestyle, the human life still subscribes to clouds and not to clocks. Though algorithms are now cheap and more efficient than subjective judgment, and though today the world has travelled quite a way from IBM's Deep Blue beating Garry Kasparov to commercial chess programmes which beat humans in no time, we still don't know about our final hour and hence we remain forever unprepared to watch and live death.

My husband's death was one of impeccable timing. In media, with the many programmes that he anchored, he knew how to spot climax, maximise on love and then suddenly one fine morning, he would just decide to end the season. That is how Annisul Huq, the Mayor of Dhaka North City Corporation, decided on his last bow and left the audience in awe. Neither the doctors nor I ever thought that he would leave us this soon.

In spite of a biopsy, with his still inconclusive diagnosis of primary cerebral vasculitis, I watched my husband for the last four months disappear into a grey zone and then eventually embark on his final journey. The Queen Square hospital—the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery—with 500 neurologists, enjoys an impeccable reputation. They are meant to rescue brains and bring patients back to a more meaningful, dignified life. But with Annis's pre-existing condition of his blood vessels narrowing since mid-June, and with the strokes that he continued to suffer starting from end July, prognosis was gloomy. I felt drained responding to questions about whether he was in or out of the ICU and whether he was conscious.

As months went by, in desperation, I imagined a recovering Annis who would eventually require neurorehabilitation. I searched for different methods that could impact his consciousness level and stumbled upon a few fascinating books that explained the value of life and why it was important for me to believe that while he lay unconscious for almost the entire period, he was actually listening to all the news I was reading out to him, that he was actually aware of the music being played for him, that he actually knew that I was there right by his side, unwilling to let go of him.

"As for myself, towards the end, I had already prepared for the last page of the book that I thought would never end, and had grown a distaste for prophecies and miracles both. And, by the third week of November, I got ready to let go of my expectations, and listed my regrets, fights, tears et al.

My mind ran faster than it could. Could deep brain stimulation help? Could we look for extensive neurorehab? Could we shift him to a ward that would ensure safe transit to intensive care, if and when required? I looked for answers and met and consulted doctors who were mostly worried about my wellbeing and recommended a slower pace and shared that reality required me to slow down. At that point, little did I know that Annis's body would actually let go and refuse to be nursed; little did I know that this man, with whom I spent three decades, was too proud to be seen in a wheelchair and would rather go as a hero, always dressed in factory shirts and kurtas, sporting cheap watches and shoes without socks.

In the meantime, the doctors also told me that in spite of being as medically fit as he was, he would still have to fight his infections. They also predicted a few bumps along the road and said that he would often survive ICU trips and would return to the ward and then with time, his body may recover enough to make space for his brain to rest and even partially revive.

During the four months of Annis's hospitalisation, what became painfully clear was the inability of medicine to predict a definite outcome. Protocols were set, exceptions applied and yet, the words of the second-century physician Galen to Roman emperors rang in my ears: "All who drink of this treatment recover in a short time, except those whom it does not help, who all die." While modern medicine takes pride in randomised trial experiments, cautious measurements and statistical strengths, it is perhaps the lack of doubt that causes medicine to fail in cases like my husband's.

As for myself, towards the end, I had already prepared for the last page of the book that I thought would never end, and had grown a distaste for prophecies and miracles both. And, by the third week of November, I got ready to let go of my expectations, and listed my regrets, fights, tears et al.

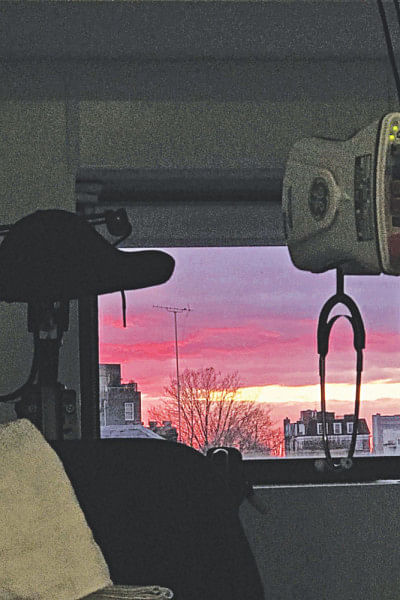

Finally, on November 30, 2017, his body caved in to sepsis in his lungs, unable to fight back as a result of intense immunosuppression. My children and I just prayed together, kissed Annis and watched him fall off the cliff, making that grand leap into the unknown. While we did that, we watched a wonderful sunset and the final sky through his window. Almost instantly, we knew that he would return to shore, somehow, someday. Maybe we'll spot his spirit in an emerging generation of dedicated public servants, setting the bar of expectation and performance higher. Maybe we'll spot him in a regular dad next door, in a regular cousin of his Noakhali clan, in an apologetic husband routinely forgetting anniversaries and birthdays, in a young businessman wanting to make a clean break, in a television anchor touching hearts, or maybe in any young pair of eyes drenched in dreams wanting to change things around.

Rubana Huq is managing director of Mohammadi Group.

Comments