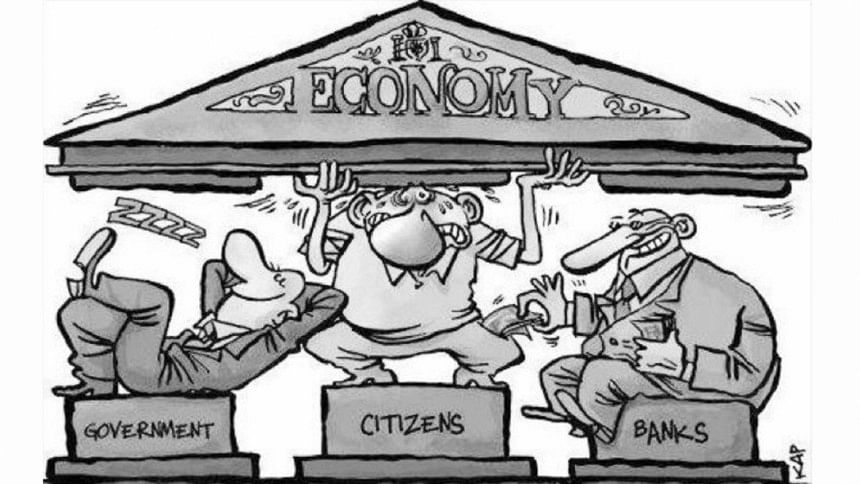

Banking Sector: A house of cards

In the last 12 years, only 20 percent of loans written off by banks in Bangladesh were recovered, according to a study by LR Global Bangladesh, an affiliate of New York based L&R Management Investments. The asset management firm also said that Bangladesh has the highest share of non-performing loans (NPLs) and lowest capital adequacy ratio (CAR) when compared to its peer economies. According to its report, non-performing, restructured and rescheduled loans stood at 17 percent of total outstanding loans at the end of 2016, meaning that the financial sector is incapable of absorbing any sudden deterioration of asset quality.

Citing a stress test carried out by the Bangladesh Bank (BB), it said that the top three borrowers in every bank comprised of half of all the bad debt. The report, after pointing out the fact that most of the banks are controlled by a handful of families and their related businesses, said that the government's planned change to extend the tenure of directors from six to nine years, as well as to increase the number of directors allowed on a bank's board from the same family from two to four, would most likely lead to "further consolidation of power in the hands of too few."

Despite the grave implications of the "facts" of the findings, the report did not really reveal anything that was not already known or suspected—that the banking sector is in complete disarray, to say the least. As in absolute terms, the size of NPL as of 2016 stood at USD 7.8 billion while restructured and rescheduled loans stood at USD 6.7 billion, according to the LR Global Bangladesh report. Yet, according to a report in the South Asia Monitor, "Several senior bank officials…say that there is a huge amount of default loans even outside of this," which "does not appear in any of the statistics" (Default loans deplete Bangladesh banking sector, March 29).

Just let that sink in for a moment. The report then says: "On paper it is shown that these loans or investments are being regularly recovered. Funds for old projects are simply being shown as loans for new projects and adjusted as loan recovery. Loans are thus being provided to non-existent projects or hundreds of crore taka are being granted as loans to projects of just a crore taka or so. The only way to adjust these loans when it is time for recovery is to make allocations for yet another project." In other words, irregularities and corruption in the banking sector have been so severe that it has literally turned into a "Ponzi scheme"—a fraudulent investment operation where the operator generates returns for older investors through revenue paid by new investors, rather than from legitimate business activities.

So how did we get here? According to the finance minister, a party has been borrowing heavily from the market and buying banks. But that is the old tapered over answer, although, there is truth to it. The problem is that the truth is much bigger and worse. So, let's look at some of the details of how we got into this mess.

By now, everyone must be well aware of the fact that the Farmers Bank, despite being relatively young, has been facing severe liquidity crises. Recently, a non-bank financial institution, First Finance, too was unable to maintain the mandatory cash reserve with the central bank.

In an investigation carried out by the BB last year, it was found that AQM Faruk Ahmed Chowdhury, former chairman of First Finance, had embezzled more than Tk 4 crore through irregularities, including loan forgery (Another non-bank falls prey to graft, loan irregularities, The Daily Star, December 19). Although this forced him to resign from the post of chairman, his replacement happened to be his brother, AQM Faisal Ahmed Chowdhury, who was also found to be an accomplice to the corruption.

Moving on, Welltext Group, the top defaulter of Basic Bank who was permitted to reschedule loans under a "special arrangement" by the BB again turned defaulter in September this year. At the time, the group that was given loans worth Tk 129 crore under the tenure of former chairman Sheikh Abdul Hye Bacchu—who is finally under investigation as per the High Court's directive—by way of irregularities, had Tk 169 crore outstanding with the state-owned bank (BASIC Bank losing battle with default loans, The Daily Star, December 22). Here is the more interesting part, the business group is owned by Majedul Haque Chisty, brother of Md Mahbubul Haque Chisty, who just recently had to step down from the board of Farmers Bank because of his alleged involvement in financial scams—as we come a full circle.

There are, of course, many more examples of such happenings in the banking sector, while the regulators continue to ponder why bailouts, one after the other, have failed to improve bank's performances. According to the South Asia Monitor report, "There is a general perception that the central bank is unable to probe into these irregularities due to political intervention. According to sources, a certain business group well known for its powerful political standing, has about Tk 68,000 crore in loans. The group directly and indirectly controls about 10 banks and financial institutions in the country. A few months ago they quietly took over the major private bank of the country too. The directors of the bank are representatives or selected persons of this group…One year ago the group's total credit from…[a] bank was Tk 1600 crore. In just a matter of months this has increased to Tk 4,500 crore."

Mind you, that report came out in March this year.

At the concluding session of the 20th Biennial Conference 2017 of Bangladesh Economic Association in Dhaka, economists and financial market analysts called for an immediate reform to restore some semblance of discipline and honesty in the banking sector. Eminent economist and former Chairman of the Department of Economics of Chittagong University, Dr M Sekandar Khan said that things would have been different in the sector had the authorities maintained ethics in their operation.

He said that half of the country's banks would not be able to continue operating if their functions were audited properly. And that, "The banks are still influencing the auditors. They are trying to cover up their liabilities by various means."

Given all of this, is it still unclear to see why the banking sector is in such disarray? Certainly not; however, what we can also be certain about is that unless things turn around, and fast, the problems plaguing the banking sector may get so severe that it will be impossible to prop up the house of cards that our banking sector has turned into, for much longer.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments