Rohingya crisis: A postscript

THE year 2017 will be remembered for many reasons but the most significant of these is perhaps the Rohingya crisis. Because of its enormous impact on Bangladesh, 2017 can easily be divided into pre-Rohingya and post-Rohingya periods. The latter began on August 25, when multiple security posts in Rakhine State in western Myanmar were attacked by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). The Myanmar military and Buddhist nationalists retaliated by mounting a brutal campaign against the ethnic Muslim minority, triggering a massive exodus that brought renewed attention to what the UN called a “textbook example” of ethnic cleansing leading to genocide.

Bangladesh, as a host to the over 600,000 refugees that fled Myanmar since August 25—more than half of the estimated Rohingya population in the country—and the several lakhs that were already there, found itself in a precarious position. It had to shelter this large refugee population as a neighbouring country, a hapless bystander in a drama played at its own expense, and now it has to negotiate their return even though it has no control over its outcome either. Four months and a much-compromised repatriation deal later, frightened Rohingyas are still in motion, casting a shadow over the ongoing peace efforts.

For Bangladesh, this presents a two-fold challenge. On the one hand, there is the need to do what best serves the interests of the country, which include repatriating the refugees as quickly as possible. For an already overpopulated country with scarce resources, this makes sense on a moral practical level. It is, after all, only natural for a country to want to put the interests of its people before that of the people from other lands.

On the other hand, there is the moral obligation of taking care of a community that experts say is the world's most persecuted, and you cannot simply wash your hands of it after having sheltered them for so long. Is there a way to reconcile these conflicting priorities? Before we get back to that, here's a brief recount of what happened so far.

WHAT FUELLED THE EXODUS?

There are many reasons prompting the Rohingyas to flee/migrate. The most immediate reason we already know; but sectarian violence is not new to Rakhine. For years, Rohingyas have been exposed to anti-Muslim campaigns, xenophobic violence, rape, murder, and arson almost as a matter of routine, and military crackdowns—or “clearance operations” as the army like to call it—have resulted in the flight of tens of thousands of people on various occasions in the past.

But there is more to this story. Because of their ethnic and religious identities, Rohingyas in Myanmar have to endure “institutionalised discrimination,” which means restrictions on their marriage, family planning, employment, education, religious choice, freedom of movement, and pretty much everything that they are entitled to. These discriminatory policies have been in place for decades.

According to a World Bank estimate, Rakhine is also Myanmar's least developed state, with a poverty rate of 78 percent, compared to the 37.5 percent national average. “Widespread poverty, poor infrastructure, and a lack of employment opportunities in Rakhine have exacerbated the cleavage between Buddhists and Muslim Rohingya,” according to the US-based think-tank Council on Foreign Relations.

All these factors, coupled with the fact that they are now denied citizenship, land and property rights as well as enfranchisement, and recognition as one of the country's 135 ethnic groups, have created an environment in which there is no hope for the members of the community. They must either perish or suffer terribly, or get out of the country to escape this fate. The Myanmar government saw to it that there was no third option.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Despite Myanmar's revisionist attempts, it is an established fact that the history of Rohingya goes back centuries. The country's political establishment and its predominantly Buddhist population consider the Rohingyas “intruders” or “illegal immigrants,” a view rooted in their supposed heritage in East Bengal, now Bangladesh, although most of them have never known life outside Rakhine.

“The Rohingya trace their origins in the region to the fifteenth century, when thousands of Muslims came to the former Arakan Kingdom. Many others arrived during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Rakhine was governed by colonial rule as part of British India. Since independence in 1948, successive governments in Burma, renamed Myanmar in 1989, have refuted the Rohingya's historical claims.” (Council on Foreign Relations)

Myanmar also doesn't recognise the label “Rohingya,” a self-identifying term that surfaced in the 1950s, which experts say provides the community with “a collective political identity.” Though the etymological root of the word is disputed, the Rohingyas say they have a right to self-identification, a right rejected by Myanmar.

Government decisions have often been driven by the Buddhist nationalist sentiment that rejects any Rohingya claim to self-identification or citizenship, making them “stateless” in their own country. According to Chris Lewa, director of the Arakan Project, a Thailand-based advocacy group, Myanmar's 1948 citizenship law was already “exclusionary,” and the military junta, which seized power in 1962, introduced a law 20 years later that stripped the Rohingyas of access to full citizenship.

Until recently, these people had been able to register as “temporary residents” with identification cards, known as white cards, that the junta began issuing to Muslims in the 1990s (which were later cancelled). Since 2014, the government decided that the Rohingyas could now identify only as Bengali.

FACTS IN NUMBERS

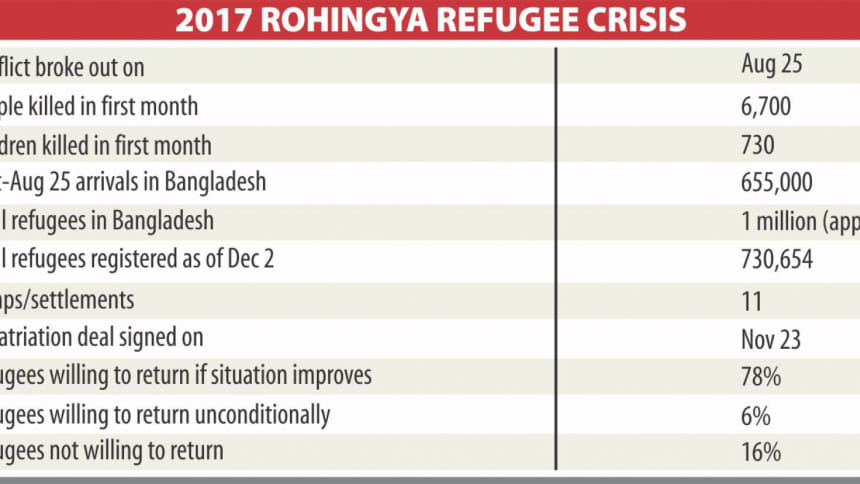

According to an estimate, over 655,000 Rohingyas, most of them children, have entered Bangladesh since the latest conflict broke out. The children, clearly, are the most vulnerable group among the refugees, followed by women. Among other vulnerable groups are the elderly, the injured and those with disabilities, who form about 10 percent of the refugee population.

Bangladesh has been providing shelter to the Rohingyas since 1978 when the first batch of refugees arrived in Teknaf (among other countries that accepted them are India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand). There was another mass exodus in 1992. Many of them, however, returned after an agreement between the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar, but a significant number of them stayed back, to be joined by another large group after a crackdown in 2016. Overall, about a million Rohingyas—730,654 of them registered by the Department of Immigration and Passports as of December 2—now live in Bangladesh.

The latest exodus is significant primarily because it is the largest and bloodiest of its kind. According to Doctors Without Borders, at least 6,700 Rohingya Muslims were killed in Rakhine in the first month alone, including 730 children under the age of five. More than 59 percent of those children were shot, 15 percent burned to death, 7 percent beaten to death, and 2 percent killed in landmine blasts.

Many women, on the other hand, were raped by the soldiers. Although there is no estimate, the Associated Press news agency, after interviewing 29 rape survivors, concluded that the army's rape of women and girls has been “sweeping” and “methodical.” The sheer scale, speed and intensity of the crimes committed against the Rohingyas are simply mind-boggling.

LIFE IN BANGLADESH

Despite the enormous costs and risks associated with hosting such a large refugee population, Bangladesh did so with relative patience and compassion so far, with help from other countries, international aid agencies, and local NGOs. There are nearly a dozen refugee camps and settlements in Cox's Bazar housing the refugees. Add to that the island in Noakhali that Bangladesh plans to turn into a temporary settlement for 100,000 refugees. The USD 280 million project, which would be complete by 2019, came under criticism from aid workers who raised objection to its location, a remote, flood-prone island that they say is “all but uninhabitable” because of the nature of its formation.

However, the initiative drew mixed reactions from the public. While some praised it, others were quick to question the rationale behind a project of this magnitude when the focus, in their view, should be on the repatriation of the refugees.

Meanwhile, the conditions of the existing camps/settlements have been reported to be dire. No one is expecting the task to be easy. Bangladesh is one of the poorest nations in the world, with over 163 million mouths to feed, and even with the help that has been received and promised so far, the burden of having to provide food, medicine, security and WASH services to an extra million people is too great to be handled with precision. But the issue being one of great international sensitivity, it attracted scrutiny from day one, and every word used, emotion expressed, and action taken by those responsible are being weighed against international standards in such matters.

So far, we've had reports of sexual exploitation (“survival sex”), child trafficking, and spread of various diseases in the camps. The sudden arrival of such a large group of people has also created tensions in local communities, with many considering them a “security risk” and a threat to their livelihoods. Which only makes it imperative that the Rohingya issue is handled with greater care, and steps are taken to improve their safety, health and dignity, with greater international assistance both for them and the host communities.

THE PATH AHEAD

On November 23, Myanmar and Bangladesh signed a deal for the possible repatriation of the refugees, although details remain vague on several key aspects such as the rights that would be granted to the Rohingyas, how their safety will be ensured in a country with raging anti-Muslim sentiment, and locations for resettlement. Also, what guarantee is there that there will not be another security crackdown or forced exodus to Bangladesh next year, or the year after? Many doubt if this deal will be the end to the Rohingya crisis, saying Bangladesh should continue diplomatic efforts for a lasting solution. Caution should also be taken about who we can trust in times of crisis, especially after the failure of India and China, previously deemed friendly to Bangladesh's interests, to side with it in its dealing with Myanmar.

Also, the failure of Saarc—a regional bloc meant to increase regional collaboration on important policy issues including the safety of member states—to intervene in the matter raised questions about its usefulness. Bangladesh needs to assess, and reassess, its relations with such countries and alliances going forward. On the other hand, as the authorities in Myanmar and Bangladesh follow up on the repatriation pact, rights activists say, they should also deal sensibly with those who want to return and those who do not.

According to a survey conducted between September and October, 78 percent of the refugees surveyed said they would willingly return if the situation “improves.” About 16 percent have no desire to return and only 6 percent would return home unconditionally, the survey added.

This is where the question of striking a balance between protecting Bangladesh's interests and the necessity for an ethical handling of the Rohingya crisis comes, one that Bangladesh cannot do on its own. Bangladesh needs more than luck at this point. Only careful planning, meaningful regional collaboration, and a need-based, forward-looking foreign policy can perhaps help in the coming days. Can Bangladesh do it? That's something to ponder about in 2018.

Badiuzzaman Bay is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments