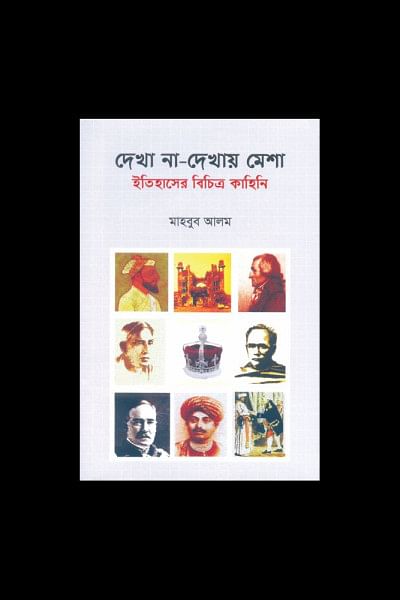

Dekha Na-Dekhay Mesha

Following a spate of some ponderous reading not infrequently embellished by otherwise unnecessary, usually superfluous, quotes and dictums from postmodernist gurus and other monishis, probably with the notion of providing their efforts with a grand "intellectual" veneer, it was refreshing to go through some relatively light, yet engrossing, material. Former career diplomat and Dhaka University History department alum, Mahboob Alam, has written just such a facile book, a kind of people's history, in Dekha Na-Dekhay Mesha. Or, is it that simple reading? Actually, a number of profound discussions (sans the pompous guru pronouncements) are woven into the twelve generally off-the-beaten track accounts of people and places in Bengal and parts of India during the Mughal and British colonial eras. Alam explains his objective in composing the book: snippets of information on events remain outside the purview of conventional history. Nonetheless, these events also leave a significant mark on the course of history, usually unobtrusively. Some of these incidences are presented in Dekha Na-Dekhay Mesha (loosely paraphrased from the original Bangla by this reviewer).

Alam begins his journey through history with an informative and interesting account of the great Mughal Subahdar of Bengal, Shaista Khan, and his multiple business transactions with the famed 17th century French gem merchant, traveler, and writer, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier. Much of the details of these encounters were recorded by Tavernier himself, although scholars have doubted the accuracy of some of those details. Two of the early encounters between the two occurred when Shaista Khan was Subahdar of Gujrat, and the final one when Khan was the governor of Bengal. Two points stand out regarding the Subahdar. One, that he was an alert and shrewd buyer, and, two, the Mughal emperor's letter writers were entrusted with the duties of a spy, and they kept a close watch on the Subahdar's activities, and without his knowledge, would report on him directly to the emperor. On Tavernier's part, he proved himself to be a crafty businessman for whom the price of the Nawab's gifts to him was more important than his munificence. Interesting character studies, with both sharing a common trait where business transactions were concerned.

The next piece deals with the last Great Mughal, Aurangzeb, and the account of an episode in his life provided by another Frenchman, the 17th century physician, traveler and writer, Francois Bernier. It revolves around, specifically, Aurangzeb's childhood tutor, a reputed scholar in India of that period, Mollah Salih, and, generally, on the emperor's thoughts on education. By the time Aurangzeb had ascended the throne, Salih had left the court. On the news of his ascension, the old teacher went to meet his former pupil in the hope that he would be rewarded with some imperial largesse (as in being made a courtier). He, instead, received an unpleasant surprise in the form of the emperor detailing the numerous wrong information he had passed off as facts to his student, and acknowledging that the only thing he had learnt from him was grammar, but that he had taught him philosophy and a slew of theories that were of no use in real life. He advised his former tutor to go back to his village and live out his days in anonymity. Aurangzeb, who was much misunderstood by several historians, probably because his outward behaviour did not always reflect his interior self, firmly believed that, because of the lack of proper education, the oriental princes, on ascendance to the throne, failed to efficiently govern their kingdoms.

The story of how the Kohinoor diamond was acquired from the Kingdom of the Punjab and deviously smuggled to England to become the crown jewel of the imperial crown is engrossing. The myth surrounding the diamond and the story of the crucial role of Governor General Lord Dalhousie, under whose 8-year rule the British held sway over a territory stretching from Burma to Peshawar, in the transportation of the jewel are recounted in engrossing detail. Another fascinating chapter deals with the Bengalis of the Mughal period getting to learn Farsi, the court language of that era. The author comes up with this telling observation, one which distinguishes between the mindsets of the two communities: even though there existed much reservation among the Hindus regarding touching, or being in close proximity to, other communities, they had no compunction in learning Farsi, unlike the Muslims of Bengal (and, indeed, the rest of India) who put forward lame excuses for not learning the imperial language, English, during a long period of the British raj. In the event, almost inevitably, gradually both the Bengali Muslims and Hindus forgot to speak Farsi, and joined the ranks of the English speakers.

An error creeps in the piece on the vanishing into thin air, as it were, of Nana Sahib, one of the leaders of what the British historians have traditionally called the Great Rebellion/Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, and what, from comparatively recent times, South Asian chroniclers have been terming War of Independence. In 1857, Lord Clive was not the commander of the East India Company forces. For me, the most enthralling story is about the superlative Indophile scholar-adventurer, the Hungarian scion of a rich family, Mark Orelstein. After having received his PhD in archeological research, he went to England, and, from there, to India in 1888 as the principal of Lahore's Oriental College. He was then all of 26 years! Orelstein was vastly interested in finding the communication route between India and China. He firmly believed it lay in the deserts of Central Asia, and, from then on, that part of the continent became his passion, so to speak.

He set about excavating parts of Central Asia. In Alam's estimate, several European archeologists dug up that region, both prior to, and following, Orelstein's efforts, but none could do it with the consummate skill of the Hungarian, or have written about his excavations with his mastery. Orelstein was evidently consumed by wanderlust, and a seemingly insatiable thirst for knowledge, as he embarked on his second expedition designed to reach Tun Huang, the gateway to the ancient Chinese empire. Probably his greatest exploit was to cajole a Buddhist monk, who was the owner of a string of caves, to part with at least some of the innumerable ancient scrolls that were housed in them. This was a signal achievement, and, even though Orelstein did not carry out any excavation of note inside India proper, he did enough for the world to remember him by, and get enriched from, his various undertakings.

A hilarious piece gives us the sometimes comical effort of Bengalis to learn English during the raj. Their trouble was rewarded with what has become known as Babu-English. It might be difficult to conceptualize that, in this age of proficient South Asian (including Bengalis) writers in the English language, that in those early years of the British raj, the English language was debased at the hands of the Bengalis. To the Bengalis' credit, though, they, through sheer effort, and by spending their own money, learnt English before the inhabitants of the rest of India's provinces. Alam provides several jocular accounts of the convoluted and flawed use of the English language by the Bengalis (e.g., "Sir, Yesterday vesper a great hurricane the valves of the window not fasten great trapidetion and palpitation and then precipitated into the precinct. God grant master long long life and many many post."). During the course of such interactions, Alam notes, the English also swiftly assessed that the Bengalis were not just clever, but glib talkers as well, and were experts at swiftly turning a situation to his/her advantage through gift of the gab.

The author also has a chapter on the British efforts to learn Bangla. Among them were the civilian officers, pucca Sahibs so to speak, who learnt Bangla from the locals and would not hesitate to abuse (including physical beating) them if they thought that their teacher had transgressed in their eyes. The civilians thought themselves as superior creatures, and the example of one such civilian officer who caned his tutor will eloquently testify to their mindset: at an inquiry into his behaviour, he expressed his ignorance that these teachers could be considered as gentlemen! A poignant picture is portrayed by the author in his story of Lord Carmichael's long and wide quest for finding his particular brand of silk handkerchief. He found it with the help of silk merchant Shudhangshu Shekhar and the handkerchief designer/maker. Alam's trenchant observation: "We continue to remember Lord Carmichael and silk merchant Shudhangshu Shekhar, but have completely forgotten the creator of the handkerchief, Abdul" (loose translation from the original Bangla by this reviewer).

Another story to savour deals with the long-drawn-out effort to rescue the library of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar from being auctioned off by his relatives after his death. There is an account of Sharat Chandra Chattopadhhay's visit to Dhaka. The round dozen of historical accounts is completed with James Revel's extended stay in Dhaka. At the age of twenty four Revel was appointed the East India Company's Surveyor General of India (or those parts, including Bengal, which were under its control). His immortal contribution to the world of geography is The Bengal Atlas. To get a fuller picture of this sketchy presentation of the twelve chapters, the reader will have to go through Dekha Na-Dekhay Mesha. It should be an enjoyable experience.

The reviewer is an actor and educationist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments