Cha Chakra: Tea Tales of Bangladesh

Faiham Ebne Sharif's first solo exhibition, Cha Chakra: Tea Tales of Bangladesh, curated by Amirul Rajiv and Naim Ul Hasan, was held at the Alliance Française de Dhaka between January 19 and 26, 2018. Because of the hustle that is life, I managed to visit the exhibition only once, that too on the closing day.

Upon entering the premises, I was greeted by a large photograph of the tea gardens, occupying the patio with its height and commanding the ground with the landscape it captured. Here was an image that attempted to show you the unending stretches of the country's tea gardens, freckled by the women that work them, whose many labours are witnessed by the trees that stand tall and old in irregular intervals. Here was an image so large that its size refused to let the horizon make the scale of this industry look small to you. At first glance, it was a scenic image of the tea gardens, a reminder of the images that have successfully built our collective knowledge of the tea industry through tourism, advertisement and brief introductions to colonial legacies. But there was no colour, no shine, and no close-up of a working woman's face. And a single white board to the right held a caption that presented you with a statistic—female workers make up around 90 percent of the tea industry's workforce. Here was an image that welcomed you with a sense of familiarity, only to remind you how little you knew, and how falsely you knew it.

Cha Chakra is a long-term documentary-photography research project by Ebne Sharif, and its narrative is styled in a no-nonsense manner. The concept note is not flowered with the language of pity, nor does it reminisce on his personal experiences and prod you to feel sympathy for this community. This is a collection of facts, written in plain words, presented with statistical findings where applicable, and most importantly, backed by images where people of the tea workers' community "become endowed with a sense of time and space," as oted by Mustafa Zaman in his preface for the project.

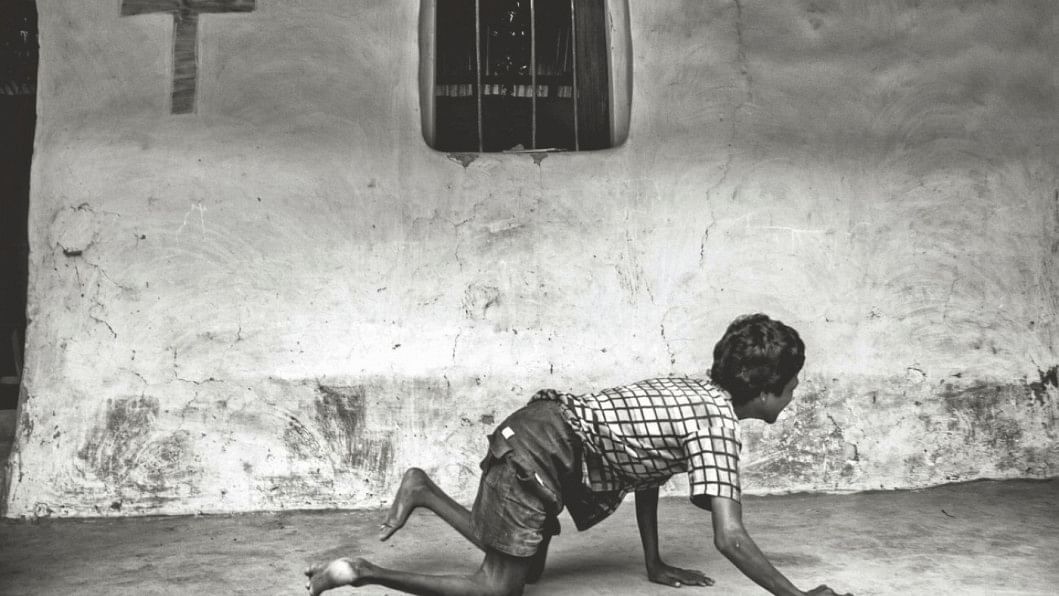

The exhibition occupied the gallery like most shows do: it began with the concept note on the wall to your left and you had to walk along the walls until the show circled back to end where it began—seemingly mundane images of workers at rest. The first photograph (also the cover photo of the accompanying publication) is of a tea worker at her house in a tea garden, while the last photograph is of another tea worker resting in a restaurant near another tea garden. Both of these scenarios are birthed out of the tea industry's exploitation of countless workers and families, located in a world where this exploitation is still permissible. And yet, here in these photographs and this show, these scenarios have been reclaimed by the resting workers, as they are captured in their ability to find footing on the same soil where they are exploited and build a home or a site for respite. As if to tell you that here is a documentary of a people whose dignity cannot be swept away by stories of their exploitation. As if to remind you that here is a story told not to make you weep, but to let them be in a world where they are usually not allowed to.

All the photographs are monochrome and framed in black. When asked why, Ebne Sharif explained, "… in this project I wanted to concentrate on the subject rather than any other thing in the photographs. So, I wanted to omit all colours and guide the viewers to the main subject within the frame. In general, viewers are quite used to seeing beautiful, oriental, coloured imagery of tea gardens, where workers are working in a lush green field, beautifully organised and geometrically formed. My intention was to show them what lies behind those beautiful images, which in fact mislead people about the workers. So, I deliberately wanted to produce images which are not present in people's minds."

But it is not just in colour where the photographer has refused to entertain misleading imageries of the tea gardens; he has also refused to let the viewer think that these are uncomplicated, straightforward stories of labour exploitation. This industry remains one of the biggest colonial operations still in existence, where the appearance of the owners may have changed but the contracts of indentured labour that have enslaved generations of migrant workers have not. There was a photograph of a cemetery of British tea planters from one of the tea gardens. As if to tell me how long ago these endless cycles of slavery began, only to still remain today. One of the photographs showed two aged workers, Hari and Sundri Nayek, who hold on to vestiges of old histories of migration and lives full of hardship. As if to tell me that this is what most of their histories are like anymore: ageing and bleak, marked by colonisers' gravestones that are up kept by the businesses of today.

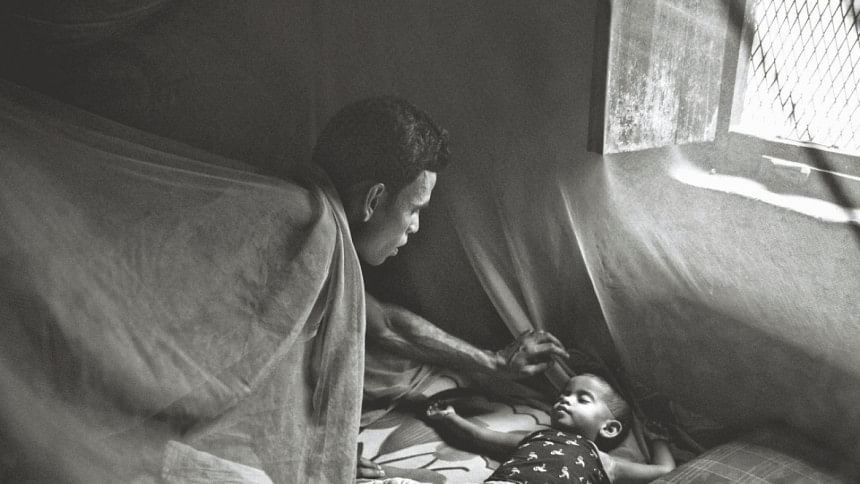

He has obviously photographed tea workers at various performances of their labour: in the fields, in the labour lines, in the factories, in the office waiting for wages. Then there are also images of play and social functions scattered here and there. And once in a while, there are images of places that this community occupies, in quiet, for you to pause in between. However, his narrative also brings you images of the people forgotten and performances of labour unacknowledged by this industry. There are images of the unwell, the old and the young, who are uncared for because all available labour and resources are to be expended on the sustenance of the tea industry; the retired and the disabled who remain uncompensated by the industry that slaved and hurt them; the substitute and contracted workers who don't even exist in the industry's statistics but are indentured to it for many more generations to come; the members of the community who remain bound to the tea gardens without permanent jobs and are unable to leave; the workers at protest to defend and keep what their labour has earned them.

Sometimes, there were also panels of photographs that juxtaposed dichotomies: homes of the managers versus homes of the workers; work versus play; the tea industry inside the gardens versus outside the gardens. And there, I was pleased by the photographer's choice to present photographs of the tea industry that exist outside the gardens: the auctions, offices, popular tea stores. As if to say it is not only the state of labour laws within the gardens that sustain this modern-day slavery; there is an entire apparatus of businesses and cultures that was built around their labour and perpetuates this system.

Ebne Sharif's work is rooted in available facts but not limited to them; he acknowledges that there are missing, unavailable facts. There are histories of migration and displacement that are hard to trace, if not impossible. He has built this work over two years, and this is the present state of the tea workers, as he has known and researched with help from the community. And his work is a job well done, which also leaves me yearning to know more of their past (or whatever semblance of a past they hold on to). He has mentioned to me that this is only a curated portion of the work and his work is unfinished, and I hope that in future publications, we will be able to see more of the community and the systems they have built to sustain themselves in these machineries of violence.

Among the guests in the opening were tea workers from the community, which gives me hope about the level of participation the community has held and will hold in this narrative. He also hopes to take the exhibition to the tea gardens in February. His respect for and acknowledgment of the community's contribution to the narrative can be seen in the way he has mentioned the name of every worker and community member in the photographs. And that makes this narrative more powerful than most documentaries of marginalised peoples, whose actual contributions to creating narratives for their communities remain constrained by subject-object binaries and the results of which keep the communities in passive roles, while the artists dominate the narrative for audiences the community cannot access.

At the show, there was also a newsprint publication with images, texts and acknowledgments to keep. But some of the darker images are difficult to look at and make sense of. Meanwhile, I wish I had more time to reflect on the work, converse further with the artist, curators and community members and write this piece. But just like the photographer himself, I acknowledge that there is still much work to be done for tea workers to build their narratives and histories. And I hope to witness many more of such work, acknowledge more of their existence, honour more of their labour, and be a better ally to them.

For those who have missed the show or simply want to revisit it, a virtual display can be seen at: faihamebnasharif.com/cha_chakra/

Maliha Mohsin is an independent writer based in Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments