Remembering World War One's Army of Bengali Workers

As the UK commemorates the Centenary of the First World War, 2014-2018, it's only fitting that one sheds more light on the experiences of the South Asians who served in the war. After all, the Indian army provided the largest volunteer army in the world. With support from Big Ideas (bigideascompany.org) and the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), I worked on this issue as a part of The Unremembered, a project commemorating the bravery and sacrifice of the Labour Corps throughout the First World War.

During the First World War, 1.5 million men served, tens of thousands of whom were labourers. More than half a million Indians served in non-combatant roles, deployed in the Indian Labour Corps. They travelled with the military, providing food, water and sanitation for soldiers and army animals, and carrying ammunition to the frontline. They built hospitals and barracks, docks and quays, roads, railways and runways. They cared for horses and mules, maintained and repaired tanks, fitted electric lights, cut wood and made charcoal. They were recruited to undertake the massive task of building modern docks and infrastructure from Basra to Baghdad, ensuring the success of the Mesopotamia campaign.

Even when the war stopped, the work of war continued. Afterwards, the labourers remained on the battlefields removing weaponry and ammunition, carrying the wounded and nursing the sick, retrieving the dead from battleside graves and creating war cemeteries. Most of the Indian Labour Corps' deaths on the Western Front were due to the cold weather and illness. They served on the Western Front of France and Belgium, Mesopotamia, Iraq, Gallipoli in Turkey, Iran, Caucasus, Salonica in Greece, the Middle East, East Africa and in Afghanistan. Indian labourers worked with the British, South Africans, Chinese, Canadians, Australians and Egyptians—to name some of the countries involved. They were World War One's army of workers and remain the unremembered today.

From the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914, the battles of the First World War spread across the world. The British and Allied Forces struggled to cope with the demand for manpower after the huge losses of men during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. A million men on both sides died or were wounded or captured during the 141 days in 1916. From January 1917, manpower was drawn from the UK, China, India, South Africa, Egypt, Canada, the Caribbean and many other places within the British Empire to redress the crisis. At the time, undivided India included present day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. Gurkhas from Nepal also served with the Indian Army. The Indian Labour Corps arrived in Marseilles, France from June 1917. Some 50,000 men served in France and Belgium from 1917 to 1920. More than 15,000 were still present in 1919, allowing the British army to demobilise more quickly.

From India, more than 100,000 men of the Indian labour Corps with Porter Corps and Jail Labour Corps served in France and Iraq. More than 3,000 men from the Indian Labour Corps died in Basra during the Mesopotamia campaign. The role of the Indian Labour Corps in the Mesopotamia campaign deserves special focus since it was there that the most Indian Labour Corps' lives (11,624) were lost. There are 1,494 Indian Labour Corps graves in France—from the Western Front, where they served, to Marseilles, the port of arrival and departure. There are 1,174 Indian Labour Corps' names written on the India Gate memorial in New Delhi. From the Indian state of Manipur, 2,000 men joined the Manipur Labour Corps of whom 500 died in service. The British War Office gives a figure of 17,347 who died on various Fronts.

While most of the Labour Corps were not exposed to the dangers of the frontline, they could get caught by medium and long range enemy artillery and sometimes even gas attacks. Many also died during the long journey to the battlefields, and most of all, from illness during their service, especially from the Spanish Flu pandemic and pneumonia. In France, the winter of 1917-1918 was bitterly cold, and respiratory diseases caused suffering and deaths. The men were given two weekly doses of treacle with opium to relieve cold, fatigue and fear.

In this setting, the enthusiasm of some accounts is striking. Kashi Nath, the captain of the Labour Corps, wrote about meetings with the Australians: "They would swarm into our barracks… exchange cigarettes… eat small bits of chapattis… teach our men how to darn socks… bring their own football and start kicking it about. Once I saw an Anzac soldier in there shaving one of our men… with two others awaiting their turn."

These new experiences were bound to affect the men who served in the Indian Labour Corps. It was the global perspective which brought about a change. In Nath's words, "The silent change… a greater independence, a higher sense of self-respect and more marked degree of alertness and smartness."

Here is an extract during the battle of Ctesiphon, November 22-23, 1915, from the memoirs of Sisir Prasad Sarbadikari, researched and translated by Dr Santanu Das of King's College London. It offers an insight into the experience of one of a group of educated middle-class Bengali youths who volunteered as a stretcher bearer for the Bengal Ambulance Corps. Sisir Prasad Sarbadikari arrived in Basra in July 1915 where the Indian army fought alongside the British against the Ottomans who were allied with Germany.

It is beyond my power to describe what I witnessed as the 23rd dawned. The corpses of men and animals were strewn everywhere. Sometimes the bodies lay tangled up; sometimes wounded men lay trapped and groaning beneath the carcasses of animals.

The highest death toll was in the front line of the trenches where there were barbed wire fences. In places there were men stuck in the barbed wire and hanging; some dead and some still living. There might be a severed head stuck in the wire here, perhaps a leg there. A person was hanging spread eagled from wire, his innards were spilling from his body.

There were spots within the trenches where four or five men were lying dead in heaps; Turks, Hindustanis, British, Gurkhas—all alike and indistinguishable in death. It fell to me and Phani Ghose to note down the names and the numbers of the wounded. [From Santanu Das, India, Empire and First World War Culture: Literature, Images, Songs, 2018]

Basra Memorial in Iraq commemorates 11,000 labourers amongst a 33,000-strong Indian force. Amongst the Indians there are thousands of Bengali names. A couple of names, for instance, point to present day Bangladesh:

Rahim Ullah, son of Jakim Muhammad of Kanalpur, Sylhet

Rahman Ali, son of Yusuf Ali of Kashimpakh, Comilla, Tippera

Sisir Prasad Sarbadikari was then caught up in the six month-long siege of Kut, Iraq from December 1915 until British General Townshend's surrender on April 29, 1916. Sisir Prasad Sarbadikari was among 10,000 Indians who were taken as Prisoners of War (POW) and endured two years of trauma including the horrific march over 500 miles to Rasel-Ayn, Syria via Baghdad in July 1916. He then worked in a number of hospitals as POW, first at Ras el-Ayn and then at Aleppo. The second extract describes the encounter with wounded Ottoman troops in a hospital in Baghdad, and the discrimination the Indian soldiers faced compared to the white soldiers:

We used to talk about our country, about our joys and sorrows … One thing, they always used to reiterate. What is your gain in this war? Why are we cutting each other's throats? You Live in Hindustan, we live in Turkey, we don't know each other, we don't have any quarrel between us…

There was one more thing noticeable amongst them – that was a common hatred of the Germans… The main cause for discontent was that whatever was good in this country, the Germans would have it first. The eggs would first go to the German hospitals and left over—if any—would then go to the Turks. The same happened with everything. We used to think that the same happens in our country but our only solace is that we are at least a subjugated nation, whereas Germany and Turkey are friends!

The discrimination that is always practised between the whites and the coloured is highly insulting. The white soldier gets paid twice as much as the Indian sepoy. The uniform of the two is different—that of the whites are better… In fact, whatever little provisions could be made is made for the Tommy (British soldier). Even the ration is different—the Tommies take tea with sugar, we are given only molasses. [quoted from Santanu Das, Race, Empire and First World War Writing]

In addition to Labour Corps, Indian seamen served on board marine transports, hospital ships and as part of the river flotilla in Mesopotamia. They also served on ships that carried out patrolling in the Bay of Bengal, Arabian Sea and on minesweeping duties in Indian waters around defended ports.

In 2012, I got involved with the Imperial War Museum's research project Whose Remembrance?—a scoping study aimed at investigating and opening up understanding of the role of colonial troops and civilians in the two World Wars. I discovered that hundreds of thousands of Africans, Indians, West Indians and other people from former British colonies had contributed to the winning of the two World Wars. Their story remains under-researched and relatively little known.

For that study, I had chosen South Asian seamen, and, to be more specific, seamen of Bengali origin who were from present day Bangladesh—the eastern half of Bengal in the then British India.

From our research at the Swadhinata Trust, we knew that the Bengali seamen formed the first sizeable South Asian community in Britain. They settled in the Midlands, Cardiff and in London's East End close to the Docks. These early Bengali seamen were commonly referred to as 'lascars'. The word was once used to describe any sailor from the Indian sub-continent or any other part of Asia, but gradually came to refer to people from West Bengal and modern-day Bangladesh. It comes from the Persian 'Lashkar', meaning 'military camp', and 'al-Askar', the Omani word for a guard or soldier.

During the First World War, more 'lascars' were needed to take the place of British sailors who had been recruited into the Royal British Navy. As a result, the numbers of Asian 'lascars' grew. By the end of the First World War, Indian seafarers made up 20 per cent of the British maritime labour force. The Indian Army was likewise a major contributor of men to the war. Nearly a million Indians served in that conflict.

Close to Tower Bridge, in Trinity Square Gardens near Tower Hill tube station, is Tower Hill Memorial, a monument that commemorates British Merchant Seamen who lost their lives in the First and Second World Wars. Many of the names on the monument indicate seamen of Bengali origin with names such as Miah, Latif, Ali, Choudhury, Ullah or Uddin. However, these named individuals only represent the privileged few Bengalis employed as British crew members, and exclude some 4,000-5,000 'lascars' who died at sea and whose names were never known.

For the First World War, the total loss of seamen of all backgrounds, recorded at Tower Hill Memorial, is 17,000. Indian sources cite that 3,427 'lascars' died and 1,200 were taken prisoner. Employed at a fraction of the normal rate for seamen, 'lascars' trapped in the engine rooms suffered a particularly high casualty rate.

Many 'lascars' received military awards for their service. The Federation of Merchant Mariners, set up in 2004 with the purpose of getting better recognition for the sacrifice of the Merchant Navy, made a point of emphasising that many Bengalis in the Merchant Navy had fought with courage and fortitude and that they, too, deserved recognition. They have been in touch with us to find any living South Asian seamen who served in the armed forces, to award the Seafarers Veterans Badge. Anybody reading this article, please do forward names of any living seaman to this author.

The Lascar Memorial in Calcutta commemorates 896 Indian Merchant seamen who died during World War I. Fireman and Trimmers from the Indian Merchant Navy are buried in Falmouth, St James's Cemetery Dover, Haslar Royal Cemetery and Penzance. The Bombay (1914-1918) Memorial commemorates more than 2,000 sailors who died in the war and have no other grave than the sea. Sailors from India, Aden and East Africa are commemorated here, and with them, those Indian dead of the Royal Indian Marine who fell in the First World War and whose graves are in Eastern waters.

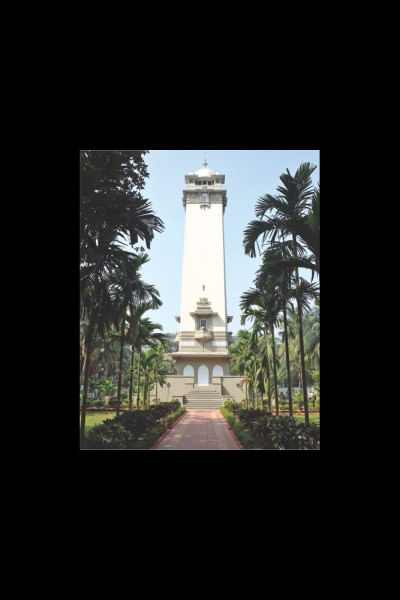

The 49th Bengalis Memorial Kolkata pays tribute to a remarkable unit. The 49th Bengalis was the only army unit to be composed entirely of ethnic Bengalis. Raised in 1917 and disbanded in 1922, it was deployed on active service in Mesopotamia.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission website databases are composed of documents recording the details and commemoration location of every casualty from the First and Second World War. A search for Bengali Labour Corps provides thousands of Indians, including Bengalis from today's Bangladesh and Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, who served in Indian Labour Corps, 49th Bengalis, Inland Water Transport Royal Engineers, Indian Railway Department, Indian Postal and Telegraph Department, Indian Survey Department and the Indian Merchant Service.

Ansar Ahmed Ullah is the UK correspondent of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments