Does architecture define a "new" Bangladesh?

A longer version of this article was first published in Clove, a magazine about South Asian culture. Read more about it and order your copy of the magazine here.

The architectural scene in Bangladesh has been thriving with a “new” energy over the past two decades or so. Bangladeshi architects have been experimenting with form, material, aesthetics, and, most importantly, the idea of how architecture relates to history, society, and the land. Their various experiments bring to the fore a collective feeling that something has been going on in this crowded South Asian country. One is not quite sure about what drives this restless energy! Is it the growing economy? The rise of a new middle class with deeper pockets? Is it an aesthetic expression of a society in transition? Is it aesthetics meeting the politics of development?

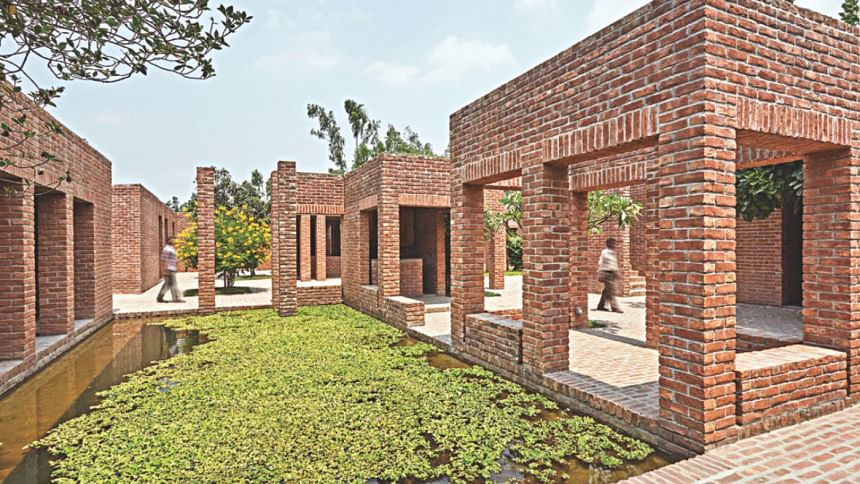

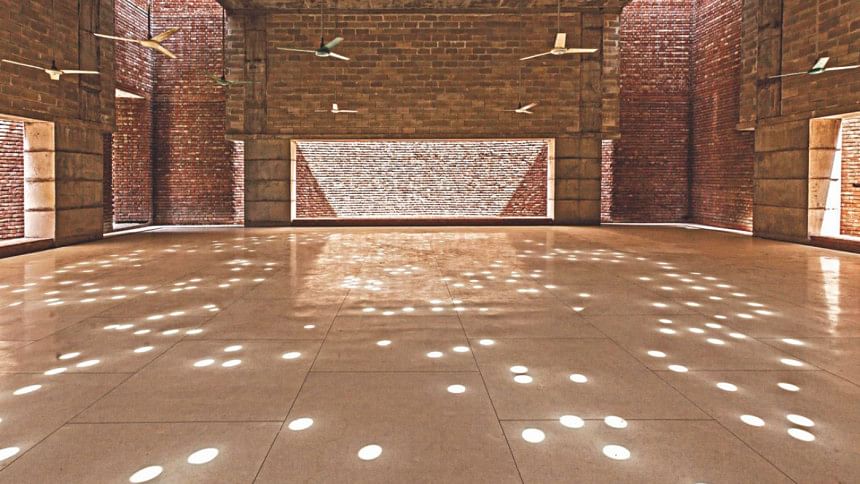

Whatever it is, an engaged observer may call this an open-ended search for some kind of “local” modernity. Two recent projects—Bait Ur Rouf Mosque on the outskirts of Dhaka and the Friendship Center in the northern city of Gaibandha—have won one of global architecture's most coveted design awards, the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, in the 2014–16 award cycle. Bangladeshi architects have been winning architectural accolades from around the world for a variety of architectural projects. High-profile national architectural competitions have created a new type of design entrepreneurship, yielding intriguing edifices. Architects have also been expanding the notion of architectural practice by engaging with low-income communities and producing cost-effective shelters for the disenfranchised. Traditionally trained to design stand-alone buildings, architects seem increasingly concerned with the challenges of creating liveable cities.

No doubt it is an exciting time in Bangladesh, architecturally speaking, even if the roads in the country's big cities are paralysed by traffic congestion and a pervasive atmosphere of urban chaos. In the midst of infernal urbanisation across the country, an architectural culture has been taking roots with both promises and perils, introducing contentious debates about its origin, nature, and future.

It is useful to look back at some of the earlier architectural energies that may shed some light on the current architectural scene in Bangladesh. The country's architectural modernism could be traced back to the 1950s, a post-Partition period of political agitation in the then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The country's first professionally trained architect Muzharul Islam (1923–2012) returned to Dhaka after completing his Bachelor of Architecture degree at the University of Oregon in 1952. Pakistan was already in trouble soon after the 1947 Partition. The newly minted country's two regions—East and West Pakistan, separated by 1,000 miles of Indian territory—clashed over their asymmetric power relationship. In this political climate, many secular-minded Bengali leaders, intellectuals, and professionals—drawn more to a mediating relationship between humanist Bengali traditions than to greater Pakistan's Islamic nationalism—searched for ways to showcase their Bengali heritage.

Considered the first modernist building in East Pakistan, Muzharul Islam's Faculty of Fine Arts (1953–56), at Shahbagh, is a telling example of how politics and aesthetics intersected. At first encounter, this iconoclastic building presents the image of another international-style building. But as one experiences its layered tropical spaces, it slowly reveals how the architect cross-pollinates a humanising, modernist architectural language with conscious considerations of climatic needs and local building materials. Deeply committed to a vision of architecture as a powerful tool for social reform, Muzharul Islam went on to design many other iconic buildings across Bangladesh and laid the foundation for a Bengali architectural modernism during the politically turbulent times of the 1960s.

One of Muzharul Islam's greatest architectural contributions to the country was to facilitate the arrival of a number of internationally known architects to build in East Pakistan during what was called the “Decade of Development,” a propagandistic slogan of Pakistan's ruling military regime. Among other architects that he helped bring were two great American masters: Louis I Kahn and Paul Rudolph. Kahn designed East Pakistan's “second capital,” which became the Parliament complex of the new nation of Bangladesh after its independence in 1971 and, Rudolph, the Agricultural University in Mymensingh.

There were other foreign architects, who also made contributions to what was, according to many, a “golden age” of architectural modernism in East Pakistan during the 1960s. The Greek architect, planner, and theoretician Constantinos Doxiadis designed the University of Dhaka's Teacher-Student Center (TSC). Designed by American architect Robert G Boughey, the new railway station at Kamalapur introduced a new chapter in the history of railway transportation in East Pakistan. Not only was it the largest modern railway station in the country, but it also embodied the modernist spirit in architecture that defined the decade. No building symbolises the advent of professional architectural education in Bangladesh during the 1960s more appropriately than Richard “Dik” Vrooman's Department of Architecture building at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology.

It was intriguing that an architectural narrative paralleled East Pakistan's political pursuit of self-rule. When it was finally completed in 1983—more than a decade after East Pakistan emerged as the new nation-state of Bangladesh and nine years after Kahn's unexpected death in New York City—the Parliament complex emblematised the political odyssey of a people to statehood.

Bangladesh's independence after a nine-month liberation war in 1971 was followed by a collective yearning to memorialise the heroism and sacrifice of the freedom fighters. When the moment of independence had finally arrived, the need for a powerful symbol to portray its meaning was urgently felt. On December 16, 1982, 11 years after Bangladesh became an independent country, the National Martyrs Monument was inaugurated. It now stands as a universally-admired iconic structure, encapsulating the nation's gratitude toward the men and women who sacrificed their lives for the Bengalis' right to self-rule.

For the new nation, the decade of the 1970s was a complex tapestry of optimism and pessimism. The uncertain period following the tragic assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family stunted the growth of a self-confident building culture. However, amidst the social tension of the 1970s, a new generation of ambitious architects burst forth onto the architectural scene of Bangladesh. The outcomes of a few national architectural competitions revealed new visions of modernity, building technology, and architectural space.

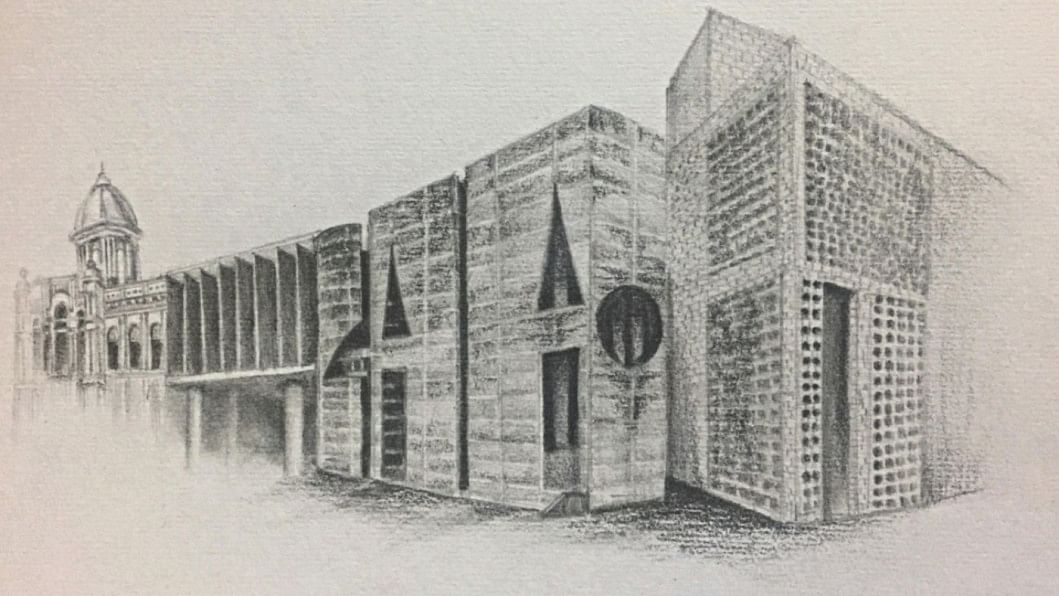

Bashirul Haq is a pioneering architect, who, in many ways epitomised the modernist impulses in Bangladeshi architecture during the decades of the 1970s and 1980s. In 1977, he won the national competition for the Bangladesh Chemical Industries Corporation (BCIC) headquarters in downtown Dhaka's Dilkusha Commercial Area. His entry showcased a new type of design energy that synthesised modernist aesthetics with a reasoned consideration for the local climate, a low budget, and an urban context.

Architecturally, the 1980s was an interesting time, as divergent ideas began to permeate architectural thinking in the country. Three stories should be mentioned. An “avant-garde” architectural study group named Chetona (meaning awareness) sought to introduce critical thinking as an essential part of architectural practice. Many architects, senior and junior— disillusioned with the prevalent role of architecture as primarily a professional practice without broader social visions and engagement with history and culture—gravitated toward Chetona, meeting at Muzharul Islam's architectural office, Bastukalabid, at Poribagh. The iconoclasm of the study group revolved around reading critical writings in architecture, criticism of current methods of architectural pedagogy, and reasoned questioning of architecture as a technical discipline. The group's reading list ranged from Rabindranath Tagore to the Franco-Swiss architect Le Corbusier to the Norwegian architectural theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz.

The influence of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA), an architectural prize established by Aga Khan IV in 1977, was also felt strongly during the 1980s. The award sought to champion regional, place-based and culture-sensitive architectural impetuses in Islamic societies. Awardees included projects in contemporary design, social housing, community development, restoration, adaptive reuse, and landscape design. Architects were inspired to look for a “spirit of place.” Regionalism was in vogue.

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture's flagship magazine, Mimar: Architecture in Development, first published in 1981 with a print run of 43 issues, influenced many Bangladeshi architects and architecture students in thinking beyond western modernism and the aesthetic conventions it allegedly created. At its inception, Mimar was the sole international architecture magazine focusing on architecture in the developing world. In many ways, the magazine's celebration of “local” expanded the scope of architectural practice in the country and gave rise to new aspirations among architects, who were willing to search for organic roots in architecture.

The new architectural aspirations coincided with the rapid urbanisation of Bangladesh and the rise of an urban middle class that spawned a flourishing culture of architectural patronage. A historically agrarian country, Bangladesh began to urbanise rapidly from the late 1980s. The country's total urban population rose from a modest 7.7 percent in 1970 to 31.1 percent in 2010. Impoverished rural migrants began to flock to major cities, particularly the capital, Dhaka, in search of employment and better lives. Its population skyrocketed from 1.8 million in 1974 to more than 6 million in 1991 and to nearly 18 million today. The capital city's massive population boom created an unsustainable demand on urban land, and in return, land values increased.

During this transitional period, real estate developers emerged as powerful economic actors in Dhaka and beyond, playing a key role in replacing traditional single-family houses with multi-story apartment complexes. Meanwhile, public-sector housing failed to meet the demand, and in this vacuum, private real estate companies flourished rapidly. As private developers became key actors in the city's housing market, a trade association was needed to regulate the real estate sector and to ensure fair competition among its members. The Real Estate and Housing Association of Bangladesh (REHAB) was formed in 1991 with 11 members. By 2017, the REHAB membership has surpassed 1500. The stratospheric rise of private real-estate developers suggested that there was a robust market for high-density, multifamily apartments, even though affordability remained a major hurdle. Many architects experimented with material, form, spatial organisation, construction, aesthetic expression, and the individual plot's urban relationship to the neighbourhood.

A burgeoning class of urban entrepreneurs—who made their fortunes in the country's export-oriented ready-made garments industry, manufacturing and transportation sectors, construction industry, and consumer market—emerged as a new generation of architectural patrons, investing hefty amounts of money to build their signature single-family houses and other projects, including apartment complexes, hospitals, shopping malls, private schools and universities, factories, spaces of worship, etc.

And, happily, architects began to find work abundantly from the mid-1990s. Design consultancy until the early 1990s was limited to a handful of architectural firms. But soon thereafter new, smaller firms, run by younger architects, began to reshape the traditional methods of architectural design practice in the country.

The liberalisation of the market, the emergence of a strong private sector, and rapid urbanisation resulted in the need for a range of building typologies and related architectural design services. In the public sector, government organisations began to evaluate the social and commercial value of aesthetic expression and hired architectural firms to compete in the building market. All of these developments ushered in a vibrant and dynamic opportunity for architectural experiments.

The last two decades in Bangladesh witnessed an intense battle of architectural ideas. The earlier attitudes to orthodox modernism or regionalism in architecture dispersed into a more nuanced landscape of aesthetic abstraction. A national architectural competition in 1997 for a museum and a monument to commemorate the history of the liberation war produced, in 2015, a 67-acre museum complex at the historic site of Suhrawardi Udyan. By proposing little building activity on the ground, the Museum of Independence and Independence Monument offer the nation a pilgrimage site without a shrine.

As architecture increasingly became a matter of public discourse, the conventional modern-vs-traditional debate became untenable as the boundaries between these aesthetic categories became blurred. Sometimes brick and concrete blended with water and green, creating building stories that somehow seemed embedded in the Bengal delta of land and water.

The ascendency of concrete as a comprehensive building material has been stunning, itself a sign of a robust building economy. Sophisticated fair-faced concrete construction in the residential, commercial, and institutional edifices suggested a building industry that had matured. The canopied poetry of Muzharul Islam's earlier work—as in the National Institute of Public Administration (1964-69) in Dhaka—the sublime ascendency of Kahn's concrete walls at the Parliament complex, and the “concrete” influence of the Japanese architect Tadao Ando were reinterpreted in a variety of local urban settings.

Architects began to look both inward and outward. The local context of the burgeoning economy and urbanity dovetailed with globalising narratives of architectural aspirations. The boundary between the local and the global was disrupted with varying degrees of success and ambivalence.

Yet, while architecture rose and prospered as individual plot-based or stand-alone practices, cities—Dhaka as a glaring example—as a whole descended into unbearable chaos. In extreme cases, Taj Mahals coexisted with overflowing dumpsters. Private oases and sumptuous cafes overlooked the ghettoised world of slums. While architects searched for Bengali roots and global gravitas in their work, they mostly failed to promote an “ethical” view of how city should function and treat all its citizens.

While globalisation went on with a cutthroat consumerist and neoliberal agenda, and architecture patronage benefitting from it, social inequality grew manifold. Architects seemed confused as to how architecture could or should also play mitigating roles in addressing the issues of social justice. Slums burned and architects rushed to the site with naïve, superficial aesthetic solutions without trying to understand the exploitative economic and political systems that blight society in the first place. The feeling that “architecture is great but the city rots” sometimes seems overwhelming.

Walking in some of Dhaka's walkable streets fronted with exclusive-looking buildings, an observer might wonder how architecture could showcase the rising stature of a developing country, while failing to play a role in making it socially just.

Adnan Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist, and currently serving as Chairperson of the Department of Architecture at BRAC University. He is the author of Impossible Heights: Skyscrapers, Flight, and the Master Builder (2015) and Oculus: A Decade of Insights in Bangladeshi Affairs (2012), and DAC/Dhaka in 25 Buildings (2017). He can be reached at [email protected].

A longer earlier version of this article was published in Clove: Magazine of South Asian Culture, London

Comments