REMINISCING HALCYON ELITE DAYS

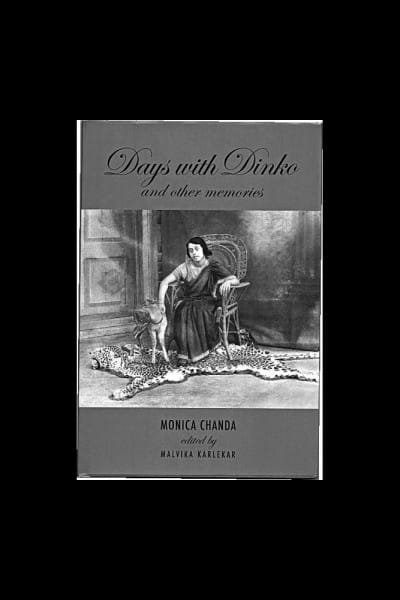

Days with Dinko and other Memories, written by Monica Chanda, and edited and published by her daughter Malavika Karlekar, is a narrative of a life largely lived in a bygone era in both East and West Bengal during the British Raj. Brief anecdotes about travels to Europe and other places in British India break the pattern of life, though definitely not the lifestyle, of people belonging to the highest rungs of the society during that colonial era of India: the ICS, or the Indian Civil Service. This was an elite service, formed by the Raj to administer its affairs in the jewel of its crown, initially recruited from the (white) British themselves, but later extended to include the Indians from a certain social background along with the requisite educational qualification (Rabindranath Tagore's elder brother was the first Indian to have been inducted into this service).

So, this is Monica Chanda's story. In her daughter's words ("Editor's Note"), "Sustained pressure from her devoted son-in-law, Hiranmay and me has yielded over 150 printed pages packed with memories of a childhood and adolescence in British India…and, in 2016, (I) began to work seriously on my mother's reminiscences." And it has presented not a bad effort either as an instance of easy reading illustrating a special lifestyle of an era long gone. Monica herself was an only daughter of an ICS officer and the granddaughter of another. Such marriages within elite social circles were rather the norm in those days, but what catches ones attention is that neither her father, nor her maternal grandfather, "despite their wide learning and commitment to education as an ideal…laid much store by girls' education." This was not a universal phenomenon among the Indian ICS officers, but was prevalent enough to have been negatively remarked upon as commentary or judgment by later academics and writers, although that is going against the admonition of that doyen of culture, Jacques Barzun: "Except among those whose education has been in the minimalist style, it is understood that hasty moral judgments about the past are a form of injustice."

Karlekar feels for her mother's unfulfilled longing: "What hurt her most was parental indifference to her education and her accomplishments as a young pianist." She was educated at home and exclusive schools, and was given piano lessons, too, but only perfunctorily and to a limited degree. She took to writing in which, in her daughter's words, there "is a Kiplingesque touch, an understated piquancy in her narration of life in the districts, of riverine journeys, of days under canvas, her much-loved pet deer and dogs, the domestic staff she became close to and the joy of 'house full' when cousins came visiting during holidays." She is essentially painting a picture of an elite life lived by her grandfather and his family in British India. Karlekar sums up her mother's life with trenchant comments: "Monica's life can be read as a metaphor, an icon of the encounter between cultures, where a father reared in the indigenous tradition and then acculturated into the ICS ethos with its strict sexual division of labour, was avowedly against formal schooling for girls…. Neither honed in ones culture nor fully at home in those practices superimposed by her father's professional life, Monica's dilemma comes through --- albeit fleetingly --- in her memoirs."

So, as Karlekar explains, in essence that her writings accurately and chronologically record the events and happenings in Monica Chanda's life. The very nature of Monica's father's job in those days introduced a standard of living that typified the ruling class of India, including that of the brown Sahibs or, the Indian ICS officers. Her father was the District Magistrate and Collector of Noakhali, Rangpur (then spelt Rungpore), and other districts of undivided Bengal, then promoted to Commissioner of Divisions, including of Dhaka (then spelt Dacca), Burdwan, and the prestigious Presidency, and ended as Member, Board of Revenue. In these capacities, he and others of his service were provided great mansions that progressively grew grander with each promotion, and which were built on vast acres of land and furnished accordingly. Their offices were also accommodated within their living homes, so spacious were they, and they had their accompaniment of all manners of servants and helps. They had tennis courts, horses/ponies, and motor launches to visit various parts of the areas they administered. A delightful array of old photographs provides a graphic representation of the lives lived by those pucca Sahibs, whether of the white or the brown variety.

Monica Chanda gives a faithful account of life as she and her family lived, in her case quite secluded within the confines of her rarefied existence, but, within those boundaries, she tried to live life as best as she could. Although a social conservative, her father was, in thought and deed, demonstrably secular in outlook. In her characterization of him, she writes: "My father had taught me to respect all religions, he did not think it necessary to go to a temple to worship God…. One could worship God anywhere, in your own home, or sitting on the banks of a river, in forests or just under a blue sky, he told me." And he got rich rewards in return. His daughter recounts how her father remained in Rungpore for about four years. And during that time there was only one incident of communal disturbance in the area.

Monica reveals another startling quality in her father, while indicating at the overt racial prejudice exhibited by at least some English ICS officers. While Commissioner of Burdwan division, her father, a tennis as well as a horse-riding enthusiast, invited the Banerjee brothers who were clerks at his office, but were good tennis players, to demonstrate their playing skills at the officers' club. They gave "an excellent account of themselves", she reveals, but also remarks that the District Magistrate and Collector, her father's subordinate, "an Englishman well-known for his anti-Indian feelings, could not have liked to see two Bengali clerks being invited by the Commissioner to come and play tennis at the officers' club."

Monica Chanda intermittently brings up an unrequited love for playing the piano. Apparently she had the potential (as some of her competent instructors) in the limited chances she got to learn from them, thought, but her family's indifference towards her future ambitions in this field led to them being quashed. She describes the elaborate marriage ceremonies of her elder brother and extended family members with particular attention to details of sarees. She also shrewdly observes in this connection: "An Indian wedding in by-gone days, celebrated in keeping with one's position in society, could be a most exhausting affair both physically and ruinous financially." To go back to the beginning, Days with Dinko and other Memories is a pleasant read of essentially a long journal where the writer has given a vivid description of an elite lifestyle lived in a bygone era of noblesse oblige, pomp and pageantry, and pucca sahibs against the backdrop of colonial rule.

Shahid Alam is an actor, and Professor, Media and Communication Department, IUB.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments