Promises Myanmar Never Kept

Nurul Amin had fled to Bangladesh along with his parents in 1991, just as more than 2.5 lakh Rohingya who escaped forced labour, rape and religious persecution in Myanmar.

At only 10, it was his first time as a refugee.

However, having lived in a makeshift camp for about two years in Cox's Bazar, the family returned home in Maundaw of Rakhine on Myanmar authorities' promise of granting them citizenship, something that they had been denied since 1982.

Years went by, but Myanmar did not grant them citizenship. Instead, they were offered national verification card (NVC), popularly known as “embassy card” which means the Rohingya are illegal migrants from Bangladesh.

Nurul, the only son of his parents, still kept his hope alive although he, like all other Rohingyas, faced restrictions on movement and right to property. They also had to pay officials for marriage and even burials.

Then came the military crackdowns in 2012 and 2016 following ethnic conflicts, making life more difficult.

“I could not stay anymore when my house was burnt like those of many others. We fled to Bangladesh to save our lives,” Nurul, father of five children, told The Daily Star, sitting along a road in Kutupalong Friday.

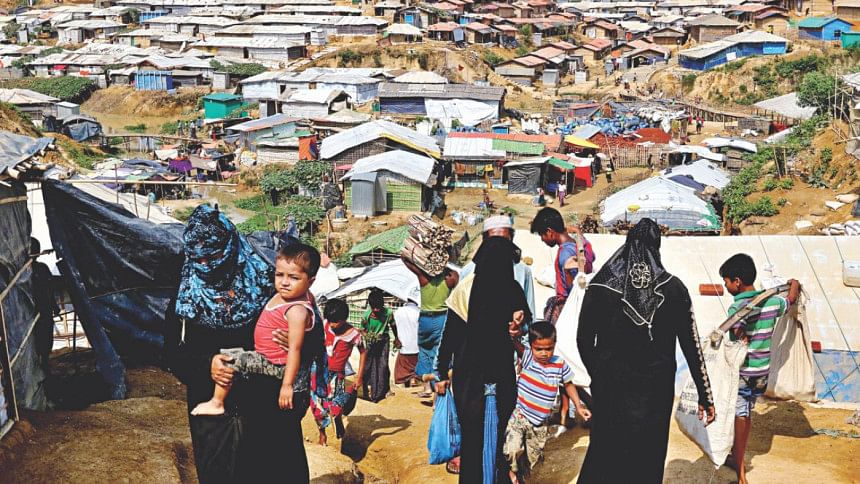

The mega camp in Kutupalong became the world's largest refugee camp in recent times after some 700,000 Rohingya fled the latest military offensive in August last year.

In the earlier waves in 1978 and 1991-92, hundreds of thousands of this persecuted minority community fled, but most of them returned home in the hope of better days. However, many of them had to flee to Bangladesh again and again.

In all, more than 1.1 million Rohingya now live in Bangladesh.

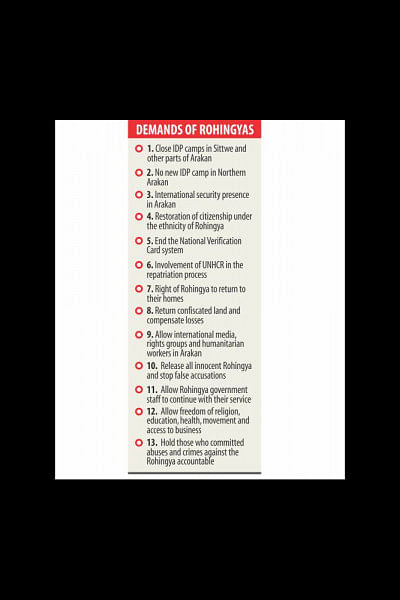

Their life and living condition in Myanmar is reflected in the 13-point demand they prepared for their repatriation as the UNSC visits the refugee camps in Cox's Bazar.

The demands include closing the camps for internally displaced people (IDP); ensure presence of international security forces in Rakhine for safety; and restoration of citizenship for the Rohingya people.

Myanmar signed a repatriation deal with Bangladesh amid global pressure in November last year, but the repatriation is yet to begin.

The UN and other rights bodies say the situation in Rakhine is still “extremely concerning” and is not conducive for the safe and dignified return of the Rohingya.

Nurul Amin does not like the refugee life in the squalid camp and wants to return to Maundaw, but he cannot trust Myanmar anymore. The Myanmar authorities say Rohingya have to first apply for the NVC, which is a gateway to citizenship.

During a recent visit to Bangladesh, Dr Aung Tun Thet, chief coordinator of Myanmar's Union Enterprise for Humanitarian Assistance, Resettlement and Development in Rakhine, said, “If you go through it [NVC], you are sure of citizenship.”

He admitted in the past it was not easy for those having NVCs to move freely. The refugees say the small number of Rohingya who took NVCs in exchange for money could move within a neighbourhood. To move from one locality to another, they have to pay much higher.

Tun Thet said, “Now, with NVCs, people [Rohingya] can move freely within their own township in Rakhine. Slowly as you build trust, then you would be eligible to have National Registration Card.”

Myanmar's social welfare minister U Win Myat Aye, after a visit to Cox's Bazar early April, said that the Rohingya were ill-informed about the NVC.

At a press conference in Yangon, upon return from Bangladesh, he stressed that NVC holders were eligible for citizenship after five months.

Nurul, however, said Myanmar did not keep its promise of granting citizenship in the past.

“How can we trust Myanmar government?” he said, reflecting the frustration of any Rohingya men and women in the camps in Cox's Bazar.

Syed Alam, 20, said he wants to go back to his motherland as soon as possible as a Rohingya, not as an illegal migrant from Bangladesh.

Alam, who studied up to class 10, the highest level of education any Rohingya can obtain in Rakhine, said the Myanmar authorities were deceiving the Rohingya in the name of repatriation.

"Having NVC means we are illegal migrants from Bangladesh. It is a tragedy that we will be treated as illegal migrants in our motherland. If one takes the card, he has to stay in the camp for the rest of his life," he added.

Abdul Kader, 60, another Rohingya, said the lives of those who took embassy cards in Rakhine were simply ruined.

“They never got citizenship cards. They also could not own property worth more than TK 30,000. So you understand the scenario," he told this correspondent, sitting at a shop at a crowded Rohingya market in Kutupalong.

The Rohingya cannot even rear any chicken, cow or goat without permission of the military, he claimed.

"They [army] visit once a month. If they find any increase in number of domestic animals, the Rohingya have to pay for that. Even if anyone wants to marry, they have to pay. Relatives also have to pay the military to bury their dead,” he claimed.

"If the Myanmar government gives us citizenship card, we will return to Myanmar immediately," said Mohammad Yusuf, who fled to Bangladesh along with his five sons and four daughters on October 9 from Akyab in Rakhine where he owns 3.5 acres of land.

“Having an 'embassy card' means you are a Bangalee and entered Myanmar illegally. Why should we take that card? Are we Bangalees? If we take NVC cards, we will never be given citizenship. We will have to return again,” Yusuf said.

Noor Mohammad, a Rohingya in Kutupalong, said the Myanmar authorities offered him NVC card for the last 15 years, but he refused. He said Hindus and Buddhists, who crossed the border to Myanmar, got the nationality cards immediately, but not the Rohingya Muslims.

“If they can get nationality cards, why shouldn't we? Why should we be foreigners in our motherland?”

Razia Sultana, a Rohingya lawyer and activist, said the Rohingya were denied government jobs, higher education, healthcare and freedom of movement since 1982.

“We live like illegal foreigners in a land where we lived for generations. This is unbelievable but true,” said Razia, who fled to Bangladesh in the 1980s with her parents.

She said the Rohingya want Myanmar to recognise them as an ethnic group of Myanmar and as citizens with all basic rights.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments