The Craft of Ray's Cinema

The nature of filmmaking in the 1930s and '40s was quite interesting. It was a time when movies in the Indian subcontinent were entirely dependent on music. A single feature length super hit movie sometimes contained even 60 to 70 songs.

Satyajit Ray was born and brought up at a time when films were just mere imitations of the Hollywood formula; in his own words, they were a mimicry of "bad Hollywood films". Outdoor shooting was beyond a filmmaker's imagination back then, so films were shot within the confines of sets. Gaudy makeup was the call of the day for both male and female protagonists, and music—no matter how unnecessary to the narrative structure—was indispensable to the movie.

In the '30s a box office hit Chandrabati used 70 songs in its entire 84 minutes length. This highly popular technique of filmmaking didn't much impress Ray. He brushed up his knowledge on films by reading books like A Grammar of the Film. Initially, his attraction towards films focused only on actors; however, these publications helped him hone his interest in global filmmaking techniques.

Around this time, he came across the work of Vsevolod Pudovkin, who helped form Ray's ideas on the techniques and aesthetics of filmmaking. Pudovkin's Film Technique and Film Acting, in particular, had an immediate and long-lasting impact on Satyajit Ray. The book was published at a time of film history when American cinema was experimenting with exciting innovations which introduced by German films, then the French, and finally, the Russians.

As a keen observer of cinema, Ray was highly impressed by the Hollywood style, which was partly influenced by the Russians and partly by the German impressionist style of filmmaking. Long before he started making films, Ray meticulously noted the shortcomings of Indian movies. In 1948, he wrote in an article titled What is wrong with Indian Films that Indian films should focus more on imaginative content than glossy aesthetics. He opined that above all, Indian films need "… style, an idiom, a sort of iconography of cinema, which would be uniquely and recognisably Indian." In this article, he states that scripts in India were mostly based on the scripts of Hollywood that had proven to be a success at the box office. That's the reason, he argues, that instead of bringing out the uniqueness of the Indian culture, the idiom of the films reflected the style and idiom of the Hollywood movies they tried to imitate.

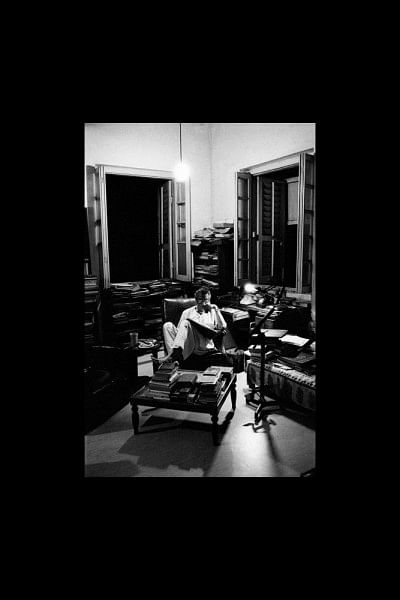

During his tenure as a visualiser at a British advertising agency in India, he was given the opportunity to visit London in the 1950s. He watched 99 films during his six-month stay in London. This was the time when he started scripting the first draft of the now iconic film Pather Panchali.

Of all the films he had watched in London, Vittorio De Sica's The Bicycle Thief inspired him the most. He believed that this film was the finest example of Italian neorealism. It drastically changed his way of reading films. After watching it he realised that films could be made without indulging in excesses of lighting or makeup, could be shot on location, and most importantly, actors need not have any prior experience in acting to make their performances immortal.

Thus when he made Pather Panchali, his shots and camera operation were unprecedented in Indian filmmaking. Similar to Italian neorealist filmmakers, Ray's penchant for shooting scenes in low lighting or his preference for using light and shadow to dramatise situations was evident in his first film.

In his debut film, Ray established that the camera and lens have a purpose and function in storytelling. In Pather Panchali, the camera never moves from one character to the other without any rational function. For example, during the death sequence of Indir Thakrun, the camera pans when Durga discovers the death of Indir Thakrun. He moves from the pan shot to close shots to intensify the tension between the two characters, Apu and Durga. Then again, Ray uses a pan shot when Durga moves away from her first encounter with death. The whole sequence was shot in a lyrical manner; pan shots follow close-ups and then return to pan shots again to show their departure from the scene.

It was arguably difficult for any director to shoot this complex sequence which so aptly portrays a child's shock at her first encounter with death—and let's not forget that Pather Panchali was Ray's directorial debut. So how did he achieve this master stroke? Ray explained in an interview with James Blue for Film Comment magazine, "I have the whole thing in my head at all times. The whole sweep of the film. I know what it's going to look like when cut. I'm absolutely sure of that, and so I don't cover the scene from every possible angle—close, medium, long. There's hardly anything left on the cutting-room floor after the cutting. It's all cut in the camera."

Before Ray came into the arena of Indian cinema, Indian films were generally filled with forced expressions of melodrama and exaggerated emotions. He pointed out in his article the ailments of Indian cinema and felt the need for a concrete narrative structure, natural sound and contextual music. Interestingly, he is the first person in Indian film history to introduce natural sound, symbolism and suggestiveness at certain climatic junctures.

A great example of his use of symbolism can be traced to the Apu trilogy. He weaved the three stories of Apu's journey with the representation of train. In the first part of the trilogy, the train was a discovery of Durga and Apu. In the sequel, it was a vehicle that separates him from his mother and took him to the city. And in the epilogue, Apu's house is close to the railway junction and the train becomes a symbol of the chaos in his life. And the chaos blooms when Apu's wife dies suddenly.

Satyajit Ray was fascinated by the Hollywood narrative style and used it rationally when required. He adopted the invisible editing style of Hollywood, which covers the cut and helps the story to flow naturally. Although he was impressed with the Hollywood style of filmmaking and storytelling, he never missed a chance to use Eisenstein's montage. For an example in Nayak, the dream sequence is the result of the main protagonist, Arindam Mukherjee's (played by Uttam Kumar) inner conflict. The director consciously gives the audience hints about the personality of this man, an actor—how he perceives the world around him, and his fear that he is drowning to his death, and will leave behind nothing but money and skeletons.

Interestingly, just before the sequence begins, the camera works from various angles; the scene almost resembles a Cubist painting. Ray consciously juxtaposes different elements and incidents which are apparently not related at first glance, but eventually the audience finds the bond linking them. The camera first tilts down to a sleeping sage who doesn't have any connection, communication of dialogue with the main protagonist, and then cuts to the main protagonist Arindam, then to his teenage fan and her mother. The mother is dressing up to look her best in front of the great actor, when the scene cuts to the scene of the protagonist smoking. Ray deliberately cuts back to the scene of the mother, who is again staring at the mirror, seemingly trying to figure out why the actor is not paying her any attention. This shot cuts to the scene of a fast moving train. Thus, through a series of shots, Ray begins the dream sequence, which thaws the ego of the main protagonist.

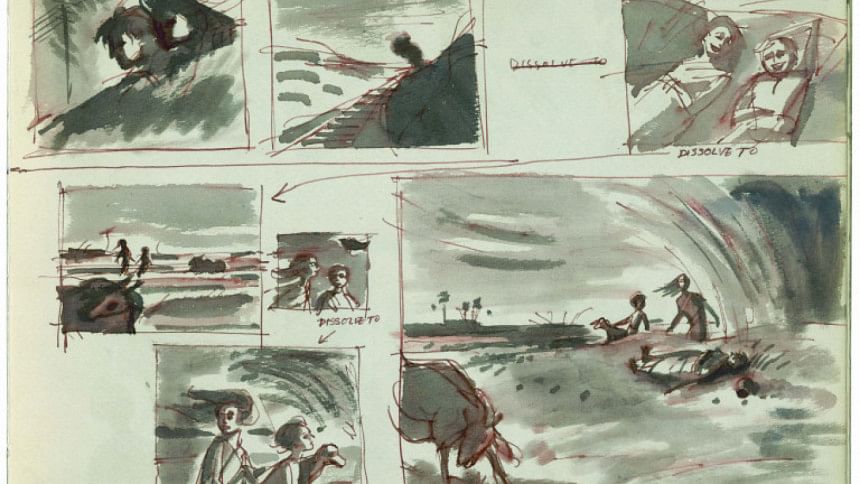

After his debut, Ray gradually changed his style of filmmaking. During the making of Pather Panchali, he made some notes and painted most of his ideas on a storyboard. Later, he adopted the Hollywood practice of scripting, but he never stopped creating storyboards for his films. In Pather Panchali, Ray made sensible use of the sitar, deep focus, soft focus, transparency and other annotations of film editing.

Ray was undoubtedly the first auteur filmmaker of South Asia. He meticulously designed the title sequences for the opening credits of his films, screenplays, and after the first few films, he also handled the cinematography, composed the music and designed the posters for his films. Ray aptly understood that the technique of storytelling, building up the mystery, scene blocking and symbolism can be attuned, but at the same time, he did not want to break away from the art of storytelling. While the French New Wave certainly inspired him, one can observe that he changed the subject of his movies but not the narrative style. He explains it best in the article Film Making: "Once in a while I feel like having a fling at a hand-held freeze-frame, jump-cut New Wave venture; but one thing stops me short here: I know I cannot have that bedroom scene that goes with it."

Ananta Yusuf is a journalist at The Daily Star.

Comments