Still waiting for the bell to ring

I am tired of visiting morgues, riverbanks and other places in search of my brother," said Rehana Banu. Her brother Pintu, an opposition activist, was picked up allegedly by plainclothes law enforcers from Pallabi on December 11, 2013. Pintu remains untraced.

Holding her minor daughter in her lap, Shumi Akhter of Chittagong had a different story to tell. Her husband Nurul Alam, also a political activist, was picked up by uniformed and plainclothes men around midnight on March 29 last year. "We thought my husband was taken to the police station and the police would send him to court the next morning... Around 4am we came to know that his body was floating on the Karnaphuli river, with his hands tied," narrated Shumi in a choked voice.

In another case, a father from Jhenaidah informed that he was able to meet his son in police custody. Subsequently, the police denied he was in their custody. With his meagre means he left no stone unturned to secure information about his missing son, of no avail.

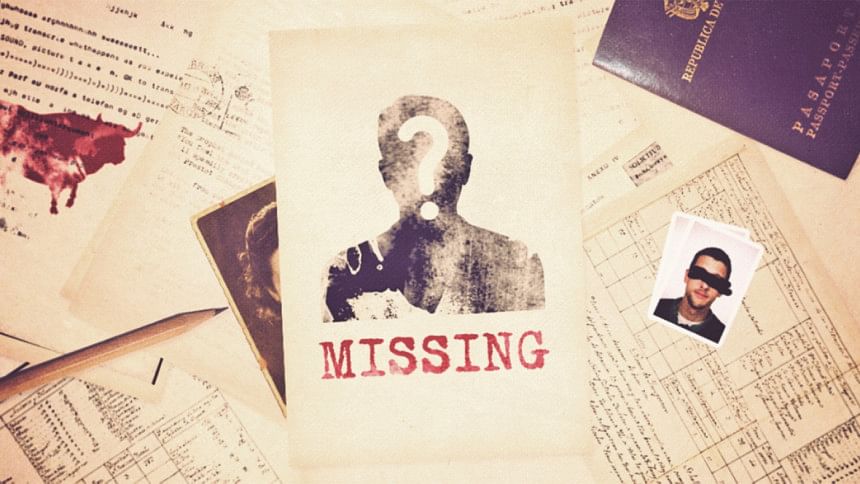

These are a few narratives of the near and dear ones of victims of involuntary disappearance at an event organised by "Mayer Dak" (Mother's Call), an organisation of the families of the disappeared, a little over a fortnight ago in the city. More than 80 families joined the event and about a score of heart-wrenching testimonies were presented. Though the families came from different parts of the country, representing a diverse range of trades and professions, and the incidents took place over a stretch of several years, a set of patterns emerges from the narratives.

In most cases victims were young political activists belonging to opposition political parties or their front organisations. In one instance a member of the student wing of the ruling party was the victim. Most families claimed that their loved ones were innocent and no case was ever lodged against them. In many cases the victims were picked up from their own homes or those of their relatives, either at night or in the very early hours of the day, and those who came to pick up introduced themselves as members of law enforcement agencies (LEAs), while in some cases those persons donned uniforms of LEAs. Interestingly, no case has been reported in which the victims were presented with a warrant, nor the alleged enforcers of the law furnished any identification documents. In most instances families or eyewitnesses reported that perpetrators used black-tinted white vans (microbuses), while in some instances they used clearly marked vehicles of a particular LEA.

After the involuntary disappearance, in all cases, family members contacted local police stations or Rapid Action Battalion offices or local public representatives, and in some cases members of parliament and ministers, but no information about the whereabouts and condition of the disappeared was ever made available to them. Most frustrating has been the refusal of the authorities to register complaints of involuntary disappearance. A case was cited where the family furnished names not only of the alleged agency involved but also of the concerned functionaries with their ranks. The police refused to take the complaint, according to these families. It was only after those specific details were taken off that the complaint was noted they have alleged.

The affected families were in unison to express their disappointment that no progress had taken place in the investigation in any of these cases. In a few instances families were threatened with consequences if they pushed the cases further.

Topping all was the case of Mohammad Shahnur Alam. He died on May 6 in Brahmanbaria Sadar Hospital. His family brought allegations of torture against members of a LEA and filed a petition in the magistrate's court. Najmun Nahar, magistrate of Brahmanbaria, on June 6, 2014 instructed the police to treat the complaint filed by Shahnur's family as the First Information Report. Within 24 hours she was stripped off her bicharik khomota (judicial authority). On June 7, the Judge's Court of Brahmanbaria ordered an "investigation for an FIR." Demanding restoration of the original order Shahnur's family filed a writ in the High Court on July 6. In at least two instances, after a lot of hurdles the families filed writ petitions and the Court instructed agencies to produce the individuals concerned. The matter remains pending for a long period of time.

The similarities in the sequence of events and the reported responses and actions of the members of the LEAs in the testimonies raise some important questions. Firstly, how is it possible for groups of rogue elements to abduct individuals, often donning uniforms and using clearly marked vehicles of recognised LEAs of the country? Secondly, why is it that the victims are mostly dissidents or members of the organisations affiliated with the political opposition? Thirdly, why is it that local police stations refuse to entertain complaints of involuntary disappearance and are adamant in rejecting complaints if they contain specific details of the alleged perpetrators? Fourthly, in cases where complaints are accepted, what precludes the law enforcers from investigating them properly and fairly? Fifthly, why, in certain cases, have members of victims' families alleged to have been kept in surveillance and threatened with severe consequences? And finally, why was the magistrate of Brahmanbaria summarily transferred and why does the higher judiciary appear to be reticent in disposing of these important petitions? All these questions beg response from those who are at the helm of law enforcement and dispensation of justice.

The distressed families drew attention of the highest office of the land to their plight. Deeply appreciating the intervention in the case involving the husband of a prominent environmental activist, they urged the prime minister to order investigation and ensure justice in all cases of involuntary disappearance with the compassion and sincerity as she did in the case concerned. They reminded the high-ups in the LEAs that the latter are duty-bound to protect every individual irrespective of their political opinion or social status and all have the right to live and die in dignity. They further reminded the wrongdoers that in the recent past, under the initiative of this government, indemnity to protect perpetrators of certain crimes has been rescinded paving the way for bringing perpetrators to justice even after decades. The aggrieved members of victims' families expressed their resolve that days of impunity are over and one day perpetrators of involuntary disappearances will also be held accountable in the same way.

Still retaining unflinching hope that their loved ones are alive, members of the families demanded their immediate return. Eight-year-old Hridi refuses to hold her disappeared father's photo anymore. Her plea: "I want to walk around holding my dad's hand." The families that have resigned to the notion that their loved ones are not likely to return want to know the details about what happened to them. Munna's father's last wish was if the state failed to bring back his son, it should at least show him where he was put to rest. His desire remained unfulfilled as he passed away a year ago. The expectation to embrace one day his disappeared brother Shahinur appears to have faded from Mehdi Hasan's mind. Now Mehdi only wants to know why Shahinur was brutally killed after being disappeared. "If I at least get an answer, I would think I have got enough justice. I don't want anything more," he informed the audience.

The loaded testimonies conveyed the message that families of the involuntary disappeared are worse off than those whose bodies were eventually found. The families of the latter had their closure with the last rites performed, religious ceremonies held, resting places identified, and inheritance and pension issues settled. Members of the families who remain traceless continue to remain in a suspended condition. They have no scope to observe the day when their loved ones had departed. Years pass by, wives do not know if they are widows now and children unaware if they are orphans.

Shujon's mother remains resolute in her hope that one day her son will be back and ring the door bell. She says she has run out of tears, but is eagerly waiting for that day to dawn. One hopes that day is not too far away.

CR Abrar teaches international relations at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments