Attention they deserve some

It was a moment of pride when Parimal Kumar Das got his autistic son's SSC results this year, but memories of being turned down by other schools flashed through his mind.

Every time he sought admission for his son Anupam Kumar Das into a new school, he would be rejected.

Finally, Parimal got recommendations from government high-ups so he could not be refused. “Still, they were reluctant,” he said.

An employee of a real estate company, Parimal never gave up on his son and finally got him admitted to a school.

However, not all children with special needs are as lucky as sixteen-year-old Anupam, whose family had the financial means and support from social groups and other parents of children with neurological development disorders.

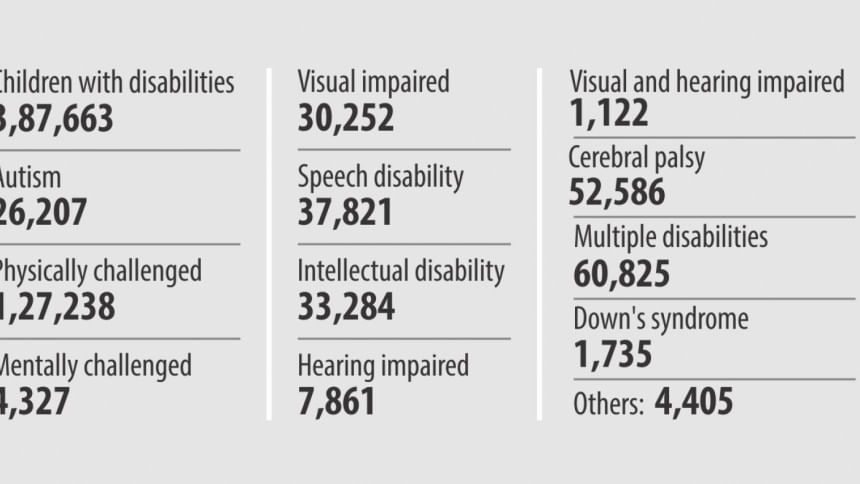

The country currently has 387,663 differently-abled children registered under 12 categories with the social welfare ministry. Public schools and other educational institutions across the country meant for them can cater to only 1,990 students between the ages of six and 16, according to the website of the Directorate of Social Services. The facilities provide free education up to secondary level to students with speech, hearing, visual, and intellectual impairments.

To decrease the gap, 62 special schools have been founded by NGOs and through other private initiatives across the country. These can accommodate not more than 7,709 students.

On the other hand, Brac,a non-government organisation, has worked for inclusive education since 2003 in close cooperation with the government. Currently, their schools have 42,288 children with speech, physical, visual, hearing, intellectual and multiple impairments.

However, it still means that a big chunk of the children remain out of the education system.

A recent report by Save the Children, a non-government organisation, identifies children with disabilities in Bangladesh as “the worst victims of discrimination” with less than 20 percent of them having access to education.

To mitigate this, guidelines issued by the education ministry in 2016 and 2017 instruct public and private schools -- both primary and secondary -- to reserve two percent of their seats for the admission of children with special needs.

There is a special quota of one percent in higher secondary education as well for the admission of children with disabilities, said Prof Harun Or Rashid, college inspector of the Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Dhaka.

Despite the government's new inclusive education policies, institutional discrimination exists due to a lack of awareness, enforcement and monitoring, said a Unicef report published in June 2014.

The private schools for children with disabilities serve as a good example of the lack of monitoring.

The government has brought such schools under its payroll.

But a system to regulate them is yet to be developed, said Mahmuda Min Ara, managing director of Jatiyo Protibondhi Unnayan Foundation, responsible for overseeing the activities of these institutions under the social welfare ministry.

“We are going to upgrade the 2009 integrated special education rules to incorporate regulatory measures,” she added.

In absence of regulation, the education expenses at these institutions also vary widely.

The parent of a student at Proyash, one of the schools under the Monthly Pay Order (MPO) system, recently said he had paid Tk one lakh in yearly fees and Tk 10,000 monthly fees for three years for his autistic son, now aged 10.

Working at a mid-level position at a local private bank, he feels the cost of education is too much for him to bear any more. He recently requested the school authorities to reduce the fees.

“I have seen many positive behavioural changes in him,” he said, while explaining why he wanted to keep his son in the school.

Back in Mirpur, Parimal said the biggest hurdle he faced in ensuring his son's education was school authorities' opposition.

But he did not back down, especially after a doctor, who had diagnosed Anupam with autism at one and a half years of age, suggested that studying and socialising with children without disabilities would help Anupam achieve a near-normal life, Parimal said in an interview at his residence in the last week of May.

While Anupam is about to embark on his next academic journey, Aakash, also 16, spends most of his days at a roadside shop playing computer games.

Aakash has autism spectrum disorder and cerebral palsy which leave him unable to speak. He, however, was quick to learn when younger, said his father Imam Ali, 50, showing his report cards from grade two and three.

“A doctor in Narayanganj treated him [Aakash] for nominal charges for about a year. He was five at the time. He learnt to walk after the treatment,” said Imam, who is now employed as a security guard at a building not far from his residence at Bihari Colony, Dhaka.

“He wanted to study more,” said Bedi Begum, Aakash's mother, but as Aakash had been bullied by other children at school, authorities insisted that he should be admitted to a special school.

“We hear on television of so many facilities that the government is providing to children like my son, but we don't get it.”

Keeping time and money aside from Imam's daily struggle to make ends meet was so difficult that his son Aakash's necessities remained unattended.

According to Parimal, Imam and other parents in a similar situation, integration of special children in mainstream schools is not impossible; the teachers have to be sympathetic towards them and deal with them with care.

Parimal said the authorities of a college recently expressed their inability to accommodate his son with the excuse that it did not have skilled teachers.

To create a friendly environment for such children, Sajida Rahman Danny, chairman of Parents Forum for the Differently Able (PFDA), said some special arrangements were needed at every institution.

“We urge the government to set the minimum standards of school building infrastructure.” Besides, skilled teachers should be employed, she added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments