Rising above the sea of "yes-men"

In Shakespeare's great tragedy King Lear, a powerful man comes to a tragic end because he surrounds himself with flatterers and banishes the friends "who will not varnish the truth to please him." Noted Dutch social psychologist Roos Vonk described how ingratiation operates: "People in high-power positions are flattered a lot, so they don't get realistic feedback from others…They get a very unrealistic image of themselves. They find it difficult to tolerate people who disagree with them, and they don't need to tolerate them, because they have high power—they can always find people who will agree with them." This could well describe the culture of sycophancy that has defined the leadership paradigm in South Asia for long.

The adherence to this culture of sycophancy goes hand in hand with the adherence to personality cult in leadership that perhaps is at the heart of our malaise. The divisions in our society have been exacerbated by the competing cults of personality among our leadership, each contesting cult tending to cull the chaff of "nay-sayers" (dissenters or independent voices) from the wheat of "yes-men" (self-serving sycophants) that leaders prefer to surround themselves with. This twin scourge has almost destroyed the integrity of our core institutions, transforming them instead into viciously inclined and malignant toll-seekers solely engaged in exploiting and relentlessly extracting from society, instead of working for societal progress and national advancement.

As human beings, all men and women are fallible. Leaders are also, after all, ordinary mortals, prone to fallibility. But they are accorded status as leaders because people expect them to rise above the foibles of ordinary mortals, to rise above themselves, to translate to a higher plane the analogy of parents who make sacrifices at their own cost in seeking to secure better lives for their progeny.

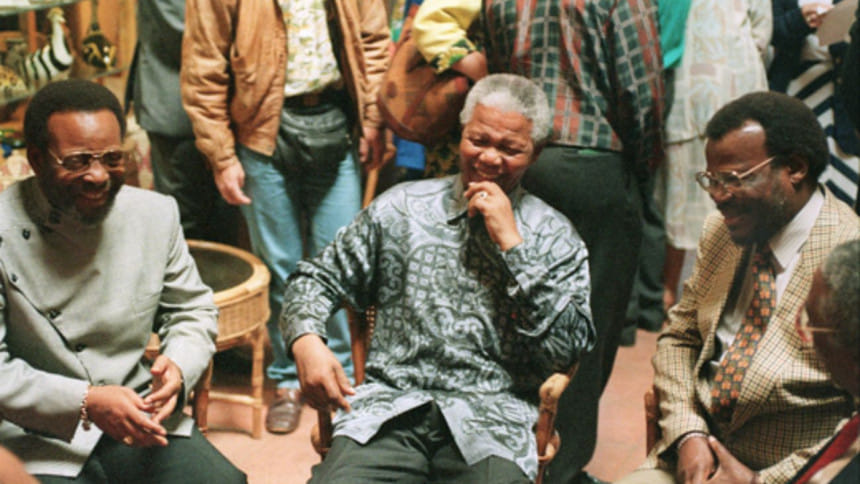

In my professional nomadic wanderings, the words of one man who had to take a long walk to freedom, traversing almost three decades of imprisonment, still ring out clearly and resonantly in my mind today, more than two decades after I first heard them spoken. I had the rare privilege, then, of being present at and witness to the proceedings of the 50th national conference of the African National Congress at Mafikeng, South Africa on December 18, 1997. At that Congress convened to elect new leadership, I witnessed at close quarters the seminal role of grassroots party workers exercising their untrammelled right to choose their leaders at local and national leaders. In his valedictory handing-over speech, Mandela, addressing his successor, among other things stated: "Let me assure you and the people of our country that, in my humble way, I shall continue to be of service to transformation, and to the ANC, the only movement that is capable of bringing about that transformation. As an ordinary member of the ANC I suppose that I will also have many privileges that I have been deprived of over the years: to be as critical as I can be; to challenge any signs of 'autocracy from Shell House'; and to lobby for my preferred candidates from the branch level upwards." Having said the above, "Madiba" (as Mandela was endearingly and reverently addressed by his countless admirers) deliberately put aside his prepared text for a few moments to ringingly assert words to the following effect: "My President, for you are from today the President of my Party and I am just an ordinary foot soldier, let me assure you of my loyalty to your leadership and decisions; but let me also assure you that even as an ordinary foot soldier of the Party, I reserve the right to criticise you when I observe you making mistakes. Do not surround yourself with 'yes men', for they will do you and the nation incalculable harm. Listen to your critics, for only by so doing will you become aware of the disaffection that ails your people and be able to address them."

There was no dearth of sycophants always hovering around Mandela, urging him to assume more powers, and to continue staying in power for ever. But this great man was quite adamant in ignoring such flattery and ill-advice. Earlier in that same year, at an important event at Port Elizabeth where I was also present witnessing history in the making, he had publicly snubbed such exhortations to him and boomingly declared in his inimitable manner of speaking: "a person who does not know when to quit is playing with fire, and I have no desire at this advanced stage of my life to play with fire and burn myself." A nation is truly blessed when it has a parent of the almost superhuman qualities of head and heart at its birth, who stays around long enough to help the child learn to walk and imbibe the important values that make life meaningful, and who knows how important it is to lead from behind, like a shepherd guiding his flock to safety out of the wilderness.

There were many divisions within the political fabric of South Africa's struggle for independence. As Chief Buthelezi, leader of the Inkatha Zulu Party (once mortal enemy of Mandela's own African National Congress prior to independence), frankly shared with me when I was meeting him in his office in the South African Parliament in Cape Town, the world should logically have witnessed rivers of blood flowing in South Africa following independence that would have dwarfed other horrific instances of blood-letting in the African continent or elsewhere in our times. But that did not happen, because its leadership had the wisdom and foresight to make a conscious effort to rise above their personal animosities, bury the hatchet in their hitherto visceral political contestations and come together on a common platform, ideological differences notwithstanding, in quest of a larger goal—the consolidation of the foundations of their newly redefined "rainbow nation". That former bitter adversaries, who literally and figuratively had sought each other's blood until very recently, were able to forge together a united nation almost overnight after reaching their goal of independence, will always remain an outstanding example of political accommodation and reconciliation in the annals of modern politics and nation-building.

Bangladeshis may have wrested democracy at the macro level for the nation, but until the practice of democracy also translates to the micro-level, to within the political parties and at the local levels of government, our democracy is at best very dysfunctional and incomplete. It will need higher standards of leadership than has been manifest so far, for us to graduate to a higher and more functional level. Mere demagoguery makes politicians, but the litmus test of true leadership is the ability of a politician to rise above mere rabble-rousing demagoguery to encompass a broader vision that seeks the common good of all the people they lead at the expense of his own personal advancement, and when he will place the nation above party and self.

But until that happens, the past shall not be past.

Tariq Karim, a former career diplomat, is currently Visiting Fellow at BRAC University.

Comments