The Culture of Intolerance and Resistance to Change - Part 2

Post independence Bangladesh had lingering sadness creeping into our lives and would overwhelm our culture at every juncture. The first years were spent trying to resuscitate the nation back from its collective grief and trauma of the war. It wasn't easy, and meant culture had to be given forceful directions given the insurmountable challenges that we were faced with. Times were changing fast, and undoubtedly it was the young providing initial indicators of the massive change in attitudes that has gone on to shape the destiny of our culture, and indeed the nation since then. The first was a realisation that we were no longer an oppressed province of the Pakistani state but an independent nation gestated out of a huge cultural conflict that led to our Liberation War. This was the firmest bastion for our culture to take off, find new meaning and gain a solid identity. It was obvious that the revivalist 'spirit of culture' induced both negative and positive benchmarks, however where it did not fail was to faithfully record the momentous steps we were to take in the rocky years ahead, in search of our real identity – the secular and liberal Bengali.

'Creativity' and 'group efforts' were two buzzwords that resonated across the cultural arena, with the young demonstrating the way forward. The group theater movement as well as rock musicians went out of their way to entertain the population not as vehicles to escape hard realities, but more to focus on the issues in hand and come out looking strong. The music of the time was a forceful reminder of who we are. From Tagore to Nazrul to Gana Sangeet down to Fakir Lalon Shah, rock and pop music, and the legions of folk maestros from rural Bangladesh, as well as new dance forms reverberated – with the young taking the helms of leadership. Wherever the young lacked in experience they compensated by discussing complex cultural issues with a senior generation. It was apparent that 'mutual respect' was growing among generations; however building 'trust' was still a long way away. Like elsewhere in the world in the seventies, Bangladesh too was going through the 'don't trust anybody over forty' phase!

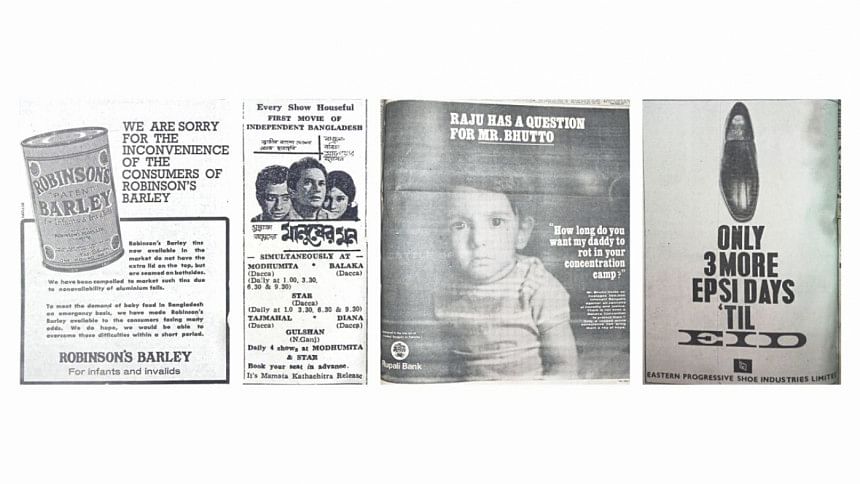

The singular aspect that changed our culture for good was, Bengalis for the first time in their history from being mere consumers were fast converting to producers. While the Government focused on agriculture and the difficult business of running the country, 'entrepreneurship' became the order of the day. From high grade muslin fabric and Manola cosmetics to vehicles built by Progati Industries to jute mills and exportable carpets to tea sold in London auctions, the 'culture of business' was steadily but surely beginning to flourish. Trading both locally and with foreign countries opened up vistas of opportunity and there was noticeable interest not only in our produce, but also our culture. Easily forgotten are the yearly Trade Fair held in Agargaon that commenced in 1973 and by 1995 became the International Fair as we know it today.

The initial 'cultural shock' of consumerism and trade was of course provided by the young. At a time when everything was in short supply, creativity thankfully was not – and from cosmetic to contraceptive producers, to paint and enamel manufacturers, everybody banked in on the 'boldness' of the young to market their wares. Gutsy television advertisement of products, together with very catchy musical 'jingles' produced by rock musicians, made waves in our 'viewing culture'. Jeans and tee shirts were in, so was bell bottoms pants and every advance made in lifestyle or fashion by the 'West' was faithfully being replicated by the young in Bangladesh. It was therefore natural that many from the 'old school of thoughts' would sound the usual alarm bells.

Resistances there were many. So-called 'progressive' Communist and socialist elements screamed their lungs out about the young 'aping bourgeois Western culture' to promote 'vulgar consumerism'; the other was the hackneyed term 'CIA plot'! On the flip side, otherwise secular yet self imposed zero-centric culture vultures and ultra-right conservative religion mongers sang almost in unison about the 'fabric of our youths morals being destroyed'. Yet there was no stopping the march of the young, for clearly while these debates carried on relentlessly in mainstream media and periodicals, they did not find acceptability of the majority population – the young.

With Calcutta and Bombay viewed as our main competitors back then, where our young met with great success is in the clear delineation that their efforts had led to the first line of resistance against the then reviled notion of 'Indian Cultural invasion'. Let us also not forget that by 1973-74 'anti-Indianism' had also become fashionable in our culture. In those early years in our efforts to stay ahead, the young didn't ditch the idea of staying 'patriotic', but at the same token they were neither interested to sacrifice our own distinct culture to the alters of the new and emerging trend of 'globalization'. It would however be decades before the word would gain currency.

With these unending pitfalls and shortcomings, our culture continued to evolve in ways many were not able to handle. The old notion of culture being an exercise discernible only to the 'faithful few' was soon giving way to shaping of 'peoples culture' which in retrospect was finding resonance across a very broad spectrum right down to the boondocks – the villages. For instance the biggest hurdle we were facing post Independence was overpopulation. For the Government of the day, the only way to face this challenge was to confront it directly and unabashedly. The Family Planning message of the Government together with sometimes brash television, radio and print media advertisement sought to placate the exigency we were up against. For a 'senior generation' it meant confronting and discussing sex and sexuality with the young without any inhibitions. For mothers at home it was time to explain to children what jonmo niyontron or birth control was all about! We were literally riding the crest of an unstoppable 'cultural revolution' when disaster struck.

The assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on August 15, 1975, placed the nation into an unexpected 'cultural trajectory' – yet our vibrant culture showed no sign of decline or decay. Indeed it was the young's ability and creativity to live with, weave and thrive within a crisis that added more dynamics to our culture, and one our new and future military rulers could least predict or even comprehend.

To be continued...

Maqsoodul Haque (Mac) is a columnist and a jazz-rock fusion musician

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments