The coordination conundrum

A section of the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp is visibly different from most other parts of the camps. The hill is dotted with shacks in close proximity as usual, but which have sturdy leakproof roofs and extra tarpaulin sheets covering the walls to protect from the monsoon rains.

At the foot of the hill hosting around 200 families is a community latrine with enclosed separate toilet facilities for men and women, unlike elsewhere in the camps where a sheet of plastic is all that shields the user. Inside the shacks however, is the same mud floor and scant belongings ubiquitous in the camps, with one major difference—residents of this camp have already received gas stoves to cook with.

The name of this idyllic (as much as is possible in a refugee camp) part of the camp is "Hope Village" and was created under a partnership between the Turkish and Bangladeshi governments. While the refugees housed there may not be much better off than others elsewhere in the camps, it may seem so to other refugees.

With a multitude of actors providing aid—often in the form of one-time donations—the lack of uniformity in what facilities and services each Rohingya refugee gets, is a given.

But this does not necessarily sit well with the receiving population. For example, Fatema Khatun who lives in Balukhali with her family of five expressed her dissatisfaction that they're not getting as much as the other refugees are. "Others are getting clothing and gas stoves. We don't get anything." Fatema kept repeating the latter statement, joined sometimes by her elderly mother-in-law squatting on the floor.

Fatema cooks for her family on a mud stove but the refugees are no longer allowed to gather firewood in the nearby forest for cooking fuel. Largescale distribution of liquid petroleum gas (LPG) stoves and cylinders to Rohingya refugees and local villagers started in mid-August in order to combat widespread deforestation in Cox's Bazar.

The latest needs and population monitoring report (July 2018) by IOM notes that refugees commonly request cooking fuel above all, followed by lighting, a stove, and clothing. Some refugees have received solar light bulbs, others like Fatema's family have not.

***

Back in August 2017 before the latest and largest influx of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, only five UN agencies and 10 national and international NGOs were operating in the refugee camps and makeshift settlements in Cox's Bazar. Fast forward a year and there are about 130 organisations in total working in the camps, including 13 local and 45 national NGOs. This is in addition to the 12 UN agencies and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

Overall responsibility of the humanitarian response still lies with the government, mainly through the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC) under the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief. Around 22 government departments and ministries, and the army, are also involved.

There is a complex system of coordination in Cox's Bazar at the moment, with a large number of agencies and other organisations grouped sector-wise under the Inter-Sector Coordination Group (ISCG).

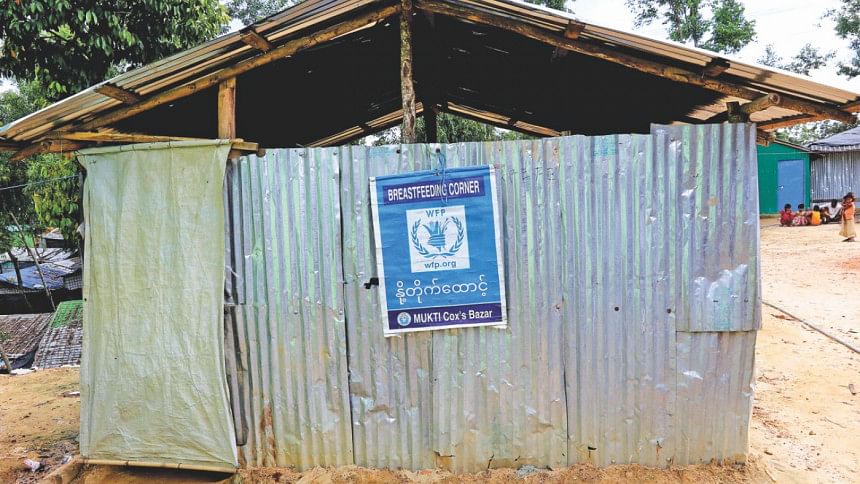

In addition to aid and humanitarian agencies, various private organisations and donors have turned up in Cox's Bazar in the months following the influx—from small, local religious organisations to foreign governments sponsoring entire camp neighbourhoods like the Turkish Hope Village mentioned above.

In such an extraordinary situation, how do these organisations coordinate the response so that some refugees do not receive more than others or are not left out of aid distributions how do they ensure access of all to basic services such as healthcare and education? Are resources being efficiently used? Do all the NGOs adhere to standards when providing services?

Coordinating the response

"NGOs coordinate their response through sectors (food security, water sanitation and hygiene, shelter, protection, site management, nutrition, etc.) working under ISCG. This is where operational and technical coordination happens," says Dominika Arseniuk, who coordinates the Bangladesh Rohingya response NGO Platform.

There are ten sectors overall, as per the Joint Response Plan (JRP), a strategy document drawn up by government and non-government stakeholders in March 2018 for the rest of the year. Their total estimate of funding needed to last the year? A whopping USD 950.8 million.

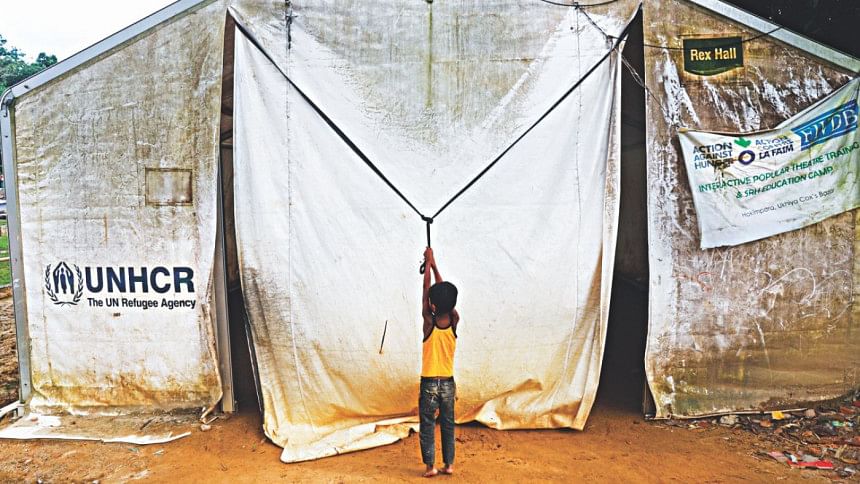

The largest number of organisations is working in the health sector, followed closely by the sector working on shelter provision. There are 32 camps across Ukhia and Teknaf in Cox's Bazar. The Kutupalong-Balukhali expansion site, known popularly as the megacamp, makes up the largest refugee camp in the world. Over 700,000 Rohingya refugees are living in just 26 sqkm of space. The JRP highlights that "congestion is the core humanitarian and protection challenge." Refugees are cramped in a space of 9 sqm, five times less than the international humanitarian standard.

According to the JRP, the onus of implementing largescale relief operations of the various international NGOs and UN agencies in the camps is on "a small set of national implementing partners who have become overstretched".

But this does not make up all the aid that the Rohingya refugees have received. In the early days after the influx, the JRP notes, many private organisations rushed to dig shallow tube-wells. Agencies, soon after, found that 21 percent of the 5,731 tube-wells needed immediate repair or replacement.

These uncoordinated aid givers "make it difficult to ensure adherence to standards", says the JRP. A common scenario in camps is latrines becoming dysfunctional, plastic roofs being blown away and huts disintegrating—all of which questions the effectiveness of aid.

Arseniuk states that aid becoming unusable or getting destroyed will continue to be a recurring problem because of one reason: all aid is meant to be temporary, hence structures are weak and need to be replaced frequently.

This can be seen firsthand in the camps with the brick roads that were laid down herringbone-style on dirt paths to allow access to heavy duty vehicles bringing in supplies. These crumble rapidly in spells of rain and require constant replacement. Tin (corrugated iron or steel sheets) roofs or concrete homes are not possible for the refugees' homes, making plastic sheets their only durable building material.

The restriction on the construction of permanent structures also means the camps cannot get electricity—which makes it difficult for aid givers to provide sustained help. Mahadu Loga mosque and madrasah in Balukhali was given a water pump and tank by a Muslim donor organisation, but with no electricity to draw water, it is of no use. "The tank is just standing there while we have to draw water from the tube-wells," says Akhter, the imam of the mosque.

There also remain drawbacks in terms of funding. "As we approach the end of August, just one third of the total funding needed for this year's response has been secured and the Rohingya are living on the brink of disaster once more. We urgently need more funding if another tragedy is to be avoided," says Fiona MacGregor, IOM spokesperson in Cox's Bazar.

Voicing their concerns

How do refugees such as Fatema, who have very little and are living in such close proximity to others who they perceive are getting more than them, bring their concerns to the notice of the relevant agencies providing services in the camps?

"When [partners] carry out needs assessments, refugees are primary information providers and on that basis the interventions are designed," says NGO platform coordinator Arseniuk. Another recourse of the refugees is to go to their majhi, selected leaders among the refugee community, who they can bring their issues to. The majhi in turn, brings these issues to the camp-in-charges, who are government appointed officials running the camps.

Outside the megacamp, and towards the 'south' where refugees live among locals, "IOM has helped establish Paradevelopment Committees in the south in which men and women from both host and refugee communities come together to identify problems and solutions for their communities," says MacGregor.

All this is meant to solve issues of overlap and underserving of refugees in the camps. "[I]f there are duplication of efforts and activities, these are brought to the table and solutions are found. Information sharing is the best way to avoid services being duplicated or concentrated in one area," says Nayana Bose, communications and PI officer of the ISCG.

***

While the abundance of aid givers—coordinated and uncoordinated—poses problems, it also allows the refugees to exercise economic choice. For example, 40-year old Gourijan was waiting outside a health post of ICNA Relief Canada with her daughter at Jamtoli camp. Right opposite were two local NGO clinics; and a maternal healthcare centre of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is also nearby.

Why did Gourijan choose to come to this particular health post over the others? The health post run by the North American aid organisation is open every day till the evening, she says. "They give good medicines and don't just send us off after giving us some medicine, they treat us until we get better and change medicines until it works," Gourijan adds.

Her 10-year-old daughter Noor has fever, cough, and skin rashes. Gesturing to the health posts opposite, she said, "They give less medicine, I don't like it."

Comments