The business of survival

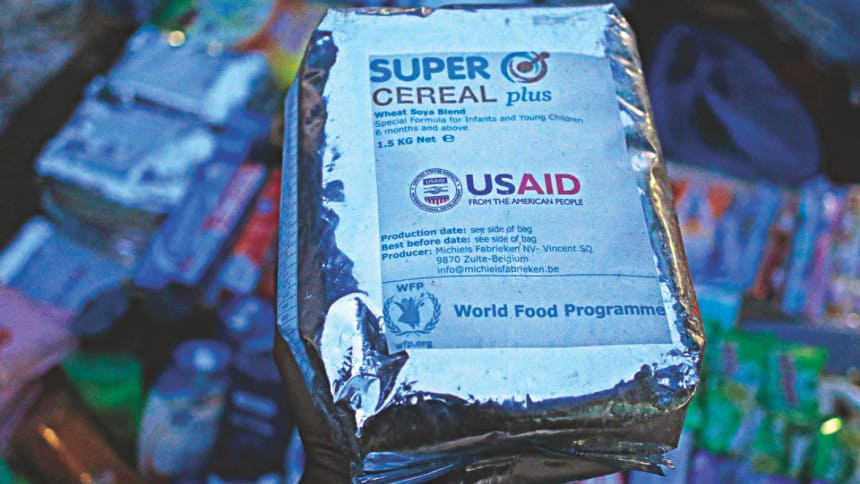

Each afternoon, a race starts for the roads heading from Ukhia to Kutupalong. Previously surrounded by thick, lush vegetation, both sides of the road are now occupied by peddlers who set up a bustling market there every afternoon. The race is to ensure every peddler gets the best spot to ensure maximum visibility of their merchandise which cannot be found in regular local markets. Hygiene products, baby food, packed dry foods of foreign brands, clothes, utensils, bed sheets, blankets bearing logos of different aid organisations are on sale here. These bazaars, which are thriving on the humanitarian aid given to the Rohingya refugees, are popularly known as "Relief Market" or "Rohingya Market".

Shamsul Alam, a majhi (an unelected Rohingya leader in the refugee camp) of Lambasiya camp who regularly sells relief items to the peddlers of this market says, "I need to repair my huts regularly after rain, I need to buy other daily necessities like salt, spices, clothes, utensils, and fuel. And, I have to do all these things by selling rice and other relief materials."

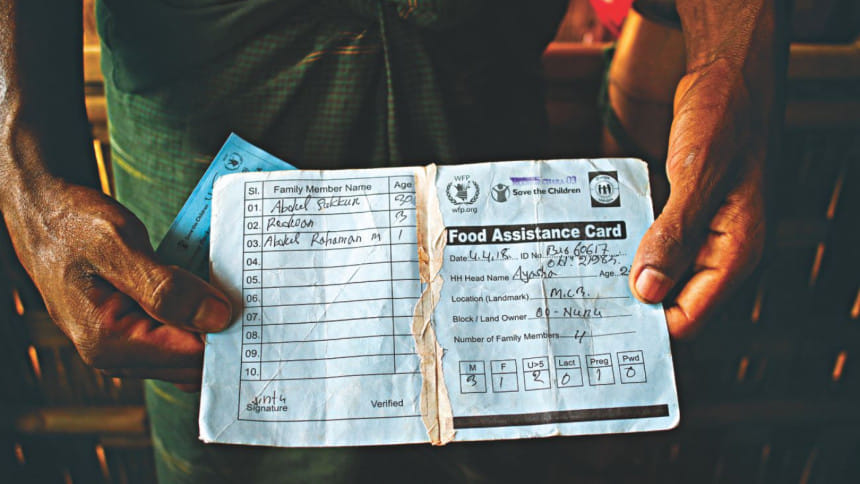

The World Food Programme (WFP), with the help of local partners, has issued a food card for every Rohingya family settled in the refugee camps. The card entitles the family to receive three essential food items—rice, lentils and edible oil—once or twice a month depending on the size of the family. According to WFP's distribution cycle:

A Rohingya family of 1 to 3 members receives 30 kilos of rice, 9 kilos lentils and 3 litres of oil, once per month.

A Rohingya family of 4 to 7 members receives 30 kilos of rice, 9 kilos lentils and 3 litres of oil, twice per month.

A Rohingya family of 8 or more people receives 60 kilos of rice, 13.5 kilos of lentils and 6 litres of oil, twice per month.

According to this system, a Rohingya family which only has only three members (regardless of their ages) get the same amount of rice, oil, and lentils, as a family which has seven members, for the first 15 days of the month. On the other hand, a Rohingya family which has eight members and a Rohingya family which has 12-15 members (extended families of this size are quite common among the Rohingya) get equal amounts of rice, lentil and oil.

Although the families who have four to eight members or more get another instalment of food at the end of the month, this method of distribution has created staggering inequality of food in the camp particularly during the first 15 days of every month. Some families have surplus amounts of rice, lentil, or oil and some families' food stock start to dwindle in just a week. In this situation, Rohingyas who have no access to storage facilities, sell these commodities sometimes to their neighbours and sometimes in the local markets.

According to Shamsul Alam, "I have to run a 10-member family. My rice stock gets exhausted within 10 to 12 days, sometimes even within a week. I have to sell rice from the remaining stock to procure other essential commodities. Bamboos to repair huts and cooking fuel are most expensive. I cannot get enough money by selling cooking oil and lentils as they are not very popular. As a result, I have to go days starving."

Donations of unpopular or unfamiliar goods also prompt the refugees to sell those things in the local market as they have no other reliable source of cash. For instance, according to Shamsul, lentils were never a part of the everyday diet of the Rohingya. Different types of vegetables and fish are their preferred food items as many of them were fishermen in Myanmar. The Rohingya also use mustard oil and different kinds of spices and salt to cook their food. However, WFP's fixed ration of rice, lentil, and cooking oil forces them to sell these items to buy some vegetables, salt, and spices which are also essential parts of their everyday diet.

Shelley Thakral, WFP spokesperson for Cox's Bazar, says in this regard, "Once the food has been given to the people for whom it was intended, it is up to them to decide what to do with it. Many refugees fled to Bangladesh with just the clothes they were wearing. In a situation where refugees have lost everything and are struggling to meet all of their basic needs, it may happen that some will sell food rations in order to buy other necessary items, such as medicine or shelter supplies."

On top of food rations, different types of hygiene products, clothes, bedsheets, blankets, and household necessities donated by various aid organisations are also sold in huge quantities by the Rohingya as they don't need, or don't know how to use, these items. Bangladeshi peddlers from Ukhiya, Teknaf, and Cox's Bazar enter into the camps to purchase these items. And, taking full advantage of the Rohingyas' unfamiliarity of local prices and their desperate need for cash, these peddlers buy these commodities at an incredibly low price.

At Balukhali-2 Camp-1, we met Abdus Sabur, one such peddler who came from Ukhia town, to purchase these relief items. He says, "Today I bought three water containers, 10 bottles of cooking oil (1 litre each), seven packets of lentils, 24 packets of sanitary pads (each contains four napkins), and five blankets. I gave them Tk 30 for each of these buckets, Tk 40 for each bottle of oil, Tk 5 for each sanitary pad packet and Tk 100 for each blanket."

It is needless to mention that the price of each of these goods is much higher in the local markets. For instance, a litre of edible oil costs no less than Tk 90 and reusable sanitary pads, which are considered new even to the markets in Dhaka, can sell for up to Tk 1200.

Abdul Arefin, who was a school teacher in Myanmar and is now a majhi at Balukhali-2 Camp-1 says, "These hygiene products like reusable sanitary pads are important for us. However, our women don't know how to use it. On the other hand, we have massive shortage of other essential commodities like fuel, salt, and spices. In the beginning, we used those sanitary pads and unusable clothes as fuel for our ovens as sometimes we cannot even cook rice due to severe fuel crisis. Since we cannot go outside the camp for selling these goods so we are bound to pay whatever price is offered to us."

Court Bazar in Ukhia town is the biggest "relief market" in the region and a hub of peddlers like Abdus Sabur. The market starts at late afternoon and runs till 9-10 pm every day. All types of relief goods are sold here in huge quantities as this place acts as the wholesale market of these types of commodities. Seeing journalists inside the market, a peddler named Masum Billah says, "Please don't do anything against us. In a way, we are helping Rohingyas by selling their goods which they don't need. Now they can buy their other daily necessities by selling these items." However, when he was asked why they offer such an unjustifiable rate to the Rohingya, Masum says, "We cannot make much profit out of these goods. There are lots of peddlers like me and all of them are selling more or less the same products in the same market."

Dr Mohammad Abul Kalam, Refugee, Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC) of the Bangladesh government says, "It is unfortunate that such valuable relief goods are not being utilised. We have repeatedly requested the donor organisations to focus more on essential commodities and healthcare for running aid programmes. Despite our requests, many donor organisations distribute many products unfamiliar to the Rohingya just to fulfil their objectives of the programme. I will request them again to make the Rohingya familiar about these products before and after the distribution."

To ensure access of Rohingya refugees to more essential commodities, WFP has started to distribute e-vouchers, an electronic assistance card that stores household data and which can be used to procure 19 kinds of commodities from designated distribution points. According to WFP spokesperson, Shelley Thakral, more than one quarter of the refugees have been provided with e-vouchers so far and the organisation expects that it will be able to cover all Rohingya families by March 2019. However, as almost 60 percent of its required funds (US$ 242 million) is yet to be resourced, the organisation is also struggling to meet the basic food needs of the refugees.

In such a fragile situation, when Rohingyas are left only with rice, lentil, and oil, without any steady supply of fuel, nutritious food, affordable sanitation, and hygiene, the desperate Rohingya have eked out their living by driving the black market of relief materials. This black market evidently sheds light on the gaps and ineffectiveness of the ongoing relief programmes and the desperate living conditions in the refugee camps.

The writer can be contacted at [email protected]

Comments