Providing safe water to refugees and local communities alike

Unchiprang camp: For nine months of the year, the Boro Chara (literally “big mountain stream”) gushes noisily from its source in the wooded hills of southern Cox's Bazar. Since last October, it has played an indispensable role in meeting the needs of Unchiprang refugee camp, where some 22,000 people now live.

It does so thanks to a treatment plant operated by UNICEF partner Oxfam on the camp's outskirts. Here, the heavy brown sediment carried down from the hills is removed from the water, and chlorine is added to make it safe to drink. The water– around 300,000 litres daily -- is then pumped to storage tanks located on high ground around the camp and fed by gravity to a network of 27 tap-stands distributed throughout the camp.

“Recently we've transferred some tap-stands to the area where families whose old homes were threatened by landslide are being relocated,” says Oxfam Programme Officer Kazal Bardhan. “And we continue to supply safe water to two Bangladeshi communities – Chakmaara and Roikum Para.”

The water plant in Unchiprang is one of only two that use surface water to provide water to the refugee population. The vast majority of Rohingya in the camps rely on water drawn from handpumps fitted to drilled tubewells, some of which reach deep underground.

Over 8,000 such waterpoints have been constructed throughout the camp areas, although only 80 per cent are currently functioning. That's because a large number of tube-wells dug in the early weeks of the crisis were badly positioned or poorly constructed and had to be closed down as they became contaminated or dried up.

“The refugees and host communities need more than 16 million litres of safe water every day for drinking, food preparation and washing,” says UNICEF WASH Specialist Rafid Salih. “That's a huge challenge, on top of which we need to construct or maintain around 50,000 latrines.”

Construction quality – and the need for maintenance – have seriously affected many latrines installed during the early phase of the crisis. Around 8,000 toilets are currently being decommissioned, due to poor construction, dysfunction or because of their location. Solutions to the challenge of safely disposing of the sludge they produce are making progress – even if the lack of space for largescale facilities in the camps is an issue (see page 19).

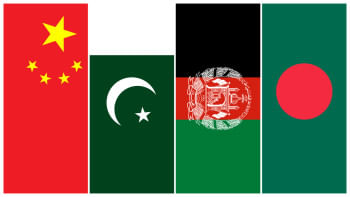

The need to provide support to thirsty host communities is another important part of WASH planning going forward. By the end of 2018, up to 200,000 Bangladeshi citizens and 150,000 refugees living alongside them are set to have access to sanitation and to safe water, much of which will be provided from four deep boreholes currently being constructed in partnership with the local Department of Public Health Engineering.

Comments