Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay's Aranyak (1939): the “Modern,” the “Non-modern” and the Nation-state

Editor's Note

Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay is a name entwined with the rural Bengal and its people. He specifically focused on the north-western districts of the undivided Bengal and brought out an amazing portrayal of the simple rustic life and its scenic beauty. Star Literature Team urges the readers to recall this amazing author on his birth month of September by presenting Aranyak as "a record of encounters between a city-based western-educated individual and an alien nature-scape on one hand and, on the other, the unfamiliar, inscrutable community life of people who live there."

One text that the romance-loving, readers of Bengali novels cannot have enough of is Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay's Aranyak. This novel, one of the most popular of the author, continues to fascinate us even after almost 80 years of its publication. The unusual (and unfulfilled) love-story involving Satyacharan, the western-educated, city-bred estate manager of the forests of Bhagalpur and Bhanumati, the tribal princess, in the book still draws the attention of readers and critics alike.

On the occasion of Bibhutibhushan's Birth Anniversary (he was born on 12 September 1894) let us, however, try to look beyond the clichéd romantic angle in order to find the text's continuing relevance for today's world – a world plagued by technology and "development." Let us instead, try to observe the nature of encounter in the text between novel, a genre imported from the west, and an ontology which is by and large non-western – an encounter between the "modern" and the "non-modern." Could this text be studied as a Bengali novelist's attempt to translate a life which is "eastern," into a narrative framework that is "western"? And where and how does the story of an emerging "nation-state" (a quintessentially "modern" concept) figure in its chronotopic structure? We must also remember in this context that during the colonial period novel in India served what Benedict Anderson called the function of projecting an "imagined community" as it developed close ties with programmes of "history-writing" and "nationalist self-fashioning." The story of Aranyak, however, happened a little later; in the beginning of the twentieth century when novelistic tradition in Bangla literature had already become well-entrenched due to the achievements of Bankimchandra, Rabindranath and Saratchandra, among others.

But first a few words about the novel's compositional details. Although Aranyak was written during 1937-39 and was published in 1939, Bibhutibhushan had planned to write this novel more than a decade earlier. This was soon after he went over to Bhagalpur in Bihar as the assistant manager of a forest estate in January 1924. He wrote in his diary in February that year, "I shall write something about the lives around this jungle . . . this jungle, its loneliness, losing one's sense of direction while riding a horse . . . about the poverty, simplicity of these people, this virile, active life, the picture of this dense forest in the pitch darkness of this evening – about all of this." (Bibhutibhushan, Smritir Rekha 188)

This novel is thus planned to be a record of encounters between a city-based western-educated individual and an alien nature-scape on one hand and, on the other, the unfamiliar, inscrutable community life of people who live there. Satyacharan, the protagonist and the observing subject, at the initial stage of the narrative might very well be a colonial naturalist and anthropologist, set out to explore a whole new world.

But this world also happens to be his motherland and his "nation." The nature of events in the text can be seen as a record of Satyacharan's explorations – his journey to his inner-self. A journey from the city to the country can help an individual to reach the depository of traditional wisdom and spirituality, and of the harmony of nature, intact community life and environmental sagacity. Satyacharan's journey in search of his true self makes him stand face to face with life, a life to be comprehended both with geographical and historical imaginations. In the second chapter, Satyacharan describes a full-moon night in Phulkiya Baihar, a land of red laterite soil:

I shall try in vain to describe the beauty of a full-moon night in Phulkiya Baihar. Anybody who does not have the first-hand experience will never be able to imagine its beauty by merely listening or reading about it. Such a world of exquisite beauty can be manifested only in a place with such vastness of the sky, such quietude, such solitude, such dense vegetation spread up to the horizon. One should experience the beauty of such a place at least once in one's lifetime; or else such a unique beauty of God's creation will elude one forever. (Aranyak 255)

The pre-historic Nature can also help the human self to tease out a realisation of longue durée from the world of the "here and now." In the sixth chapter, Satyacharan writes, "These forests and hills have remained unchanged since time immemorial. In the distant past, when the Aryans crossed the Khyber Pass and marched into the land of five rivers, this forest was the same. The night when Gautama Buddha left his newly-married wife behind, this hilltop manifested the same smiling demeanour in the middle of a moonlit night, like today" (Aranyak 288).

The uniqueness of the text, however, lies in the fact that in Aranyak Bibhutibhushan showcases not merely the changeless beauty of nature but he also tells the stories of people who inhabit the land. He tries to document different layers of human history; the historical dynamic that is entwined with the evolution of the human society of this land as human communities march towards modernity; from stages of hunting, farming and foraging to agriculture and gradually towards industry and commerce. Agriculture is seen in the text as a major human intervention in the ecosphere of this land. Agriculture also becomes instrumental in the reshuffling of social hierarchy; a reshuffling that in the Indian context involves both class and caste. It is agriculture which makes a world of difference between the indigenous tribes and lower-caste people and Rajputs and other high-caste Hindus. In Risley's "Report," of 1890, we find that certain tribes and castes in India could be grouped in terms of their unwillingness to work in the field. Forests which used to be the main source of sustenance for these people gradually became out of bounds due to the pressures of colonial rule. In Aranyak Dobru Panna (the erstwhile king of this land and one who claims that in his youth he had fought against the East India Company) and his people represent this group. When Satyacharan asks Dobru if his family members practise agriculture, he proudly declares, "Such things are not practised in our family. Hunting is the greatest means of livelihood and hunting with spears is the most glorious thing" (Aranyak 329). In present-day terms, they are the subalterns who have not in the bandwagon of "development." For agriculture there is an extremely complex equation existing between zamindars who own vast stretches of land and pay revenue to the British government, their subjects who cultivate the field and pay taxes, landowners, moneylenders and middlemen, landless migrant labourers and small-time professionals like village-pundits, priests, quack-doctors, artisans, craftsmen, poets and even folk dancers. Economics and land settlements are chief organising principles behind the social changes that affect lives of the rural people represented in the text. This text is, thus, in a way, is a record of the changes taking place in the field of agriculture in the Indian subcontinent: from small-scale cultivation to a large-scale profit-making exercise. It is, therefore, no wonder that a city like Kolkata which was an important centre of colonial economy during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century is very significantly posited on the margin of this text. It is flow of capital that links Kolkata with the forests of Bhagalpur and Purnia. We also notice that Kolkata exists as a leitmotif in the form of a hyper real Kolkata that the rural characters wish to visit. (Satyacharan asks a number of villagers whether they have ever visited Kolkata.) A desire to visit Kolkata, therefore, becomes like a trope to reach modernity and "development" and a means to become a "subject" of history.

Bibhutibhushan, however, has a problem. He has to translate the stories of the people whom his protagonist encounters into the language of realism if he wants his text to be regarded as a novel. In the lives of the characters that Bibhutibhushan presents in Aranyak, "historical time" is intimately associated with "mythical time." If history is all about calendrical time and linear progression of events, "mythical time" is circular or spiral in nature. It is evident from the text that the cultural practices of these people, their cosmology, their eschatology – their belief-systems do not conform to the idea of realism. Raju Pandey, one of many rustic characters in the text, is confident that every morning the Sun rises from a cave in Udaypahar; the cave a sadhu from Munger had actually visited. Dasharath Jhandawala and Ganori Tiwari claim to have seen Tnaarbaro, the god that protects wild buffaloes from falling into the traps set by poachers. The novelist looks for a different kind of artistic solution. Instead of trying to become a historian of the tribe he assumes the role of a chronicler. In the text, he presents characters and events in their lives in a

manner which blends the approach of a folklorist with that of a sociologist. Satyacharan tells us how Ganu Mahato used to tell him stories of flying snakes, live stones and of new-born babies who could walk about. As the narrative progresses, Satyacharan becomes a storyteller himself. He describes, almost in a surreal manner, the celebration of Jhulan festival throughout a full-moon night on top of the Dhanjhari hills, by tribal men and women; how they sing and dance all night long, encircling an ancient banyan tree. He tells us the story of Jugalprasad whose only passion in life is to beautify Sarasvati Kund by bringing seeds and saplings from many places and planting those. Storytelling is the art of repeating stories. The storyteller turns his experience into a part of the experience of his listeners; in his art most marvellous things are told with greatest accuracy and no interpretation is forced. Bibhutibhushan, like a true storyteller, shows us ways of creating a different kind of historicity and a narrativity whose objective is not merely to pass on information but to exchange wisdom. He forsakes the pattern of plot-progression followed by most "realist" novels: a pattern driven by the necessity of telling "what happens next?" He successfully blends the "realism" of the calendrical time of the assistant manager of a forest estate with the "fantasy" of the storytelling time of an oral tradition.

But this act of "negotiating the novel" in the text also takes the narrator to the limits of human understanding. Satyacharan has to negotiate with the bizarre incident in the Bomaiburu jungle which involves Ramchandra Singh, the land surveyor and his son. They are visited by the ghostly figure of a mysterious woman in the middle of the night in an area where no one is supposed to be present for miles around. The experience leaves Ramchandra Singh mad. Satyacharan's "modern" self is at a loss to explain such an incident from the world of the "non-modern." It is, however, merely not the element of the "fantastic" that Bibhutibhushan struggles hard to "translate" for his urban readers. The complex historical forces which are at work in the jungle society sometimes take him completely off-guard. Manchi, the young Gangota woman, wife of a migrant labourer, vanishes from the forest-land as local people apprehend that the lure of the city Kolkata has driven her to elope with a Rajput farmer. Dhaturia, the teen-aged practitioner of "chakkarbaji," a form of folk dance, who is very passionate about his art, meets with a tragic death. The dead body of this young talented artist whose life-long ambition has been to perform in front of a Kolkata audience is found near the railway tracks, a symbol of colonial modernity.

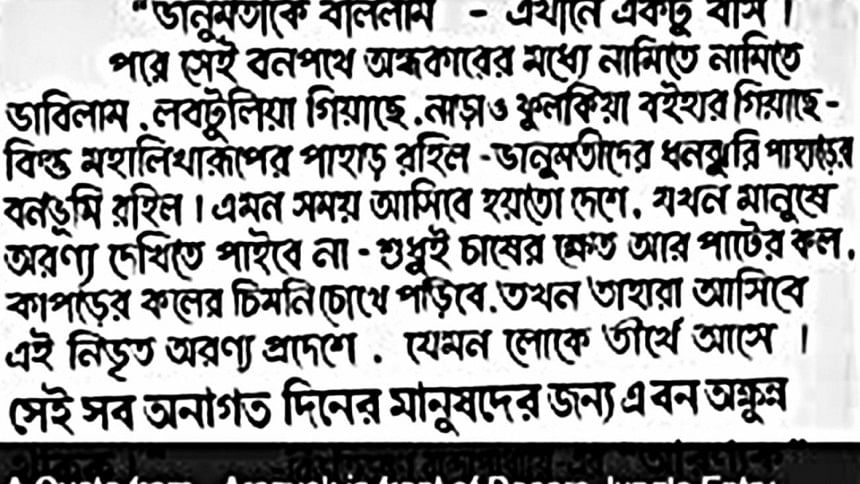

The text, however, throws up the most significant aporia when Bhanumati asks Satyacharan "Which way is Bharatbarsha?" I do not think that even today, in this globalized age, we can give a definitive answer to Bhanumati. The split between the performativity of the lives of the subaltern and the official nationalist discourse is still wide open in our subcontinent. We should also re-read Aranyak in the context of "sustainable development," a burning issue of contemporary times, as it provincializes the idea of "development". Satyacharan, in the very end of the novel, asks, "What does man want – development or peace of mind? What will anyone do with development if one does not gain happiness in the process?" (Aranyak 382). The other question, however, is that we need to ask ourselves, "Where does happiness lie?" Does the path taken by the 'modern' (and postmodern) man which, through genetic engineering, heavy industry, nuclear power-plants, service industry, global capital and informatics, take him to happiness? We do not have an answer.

Dipankar Roy teaches in the Department of English, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan. He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments