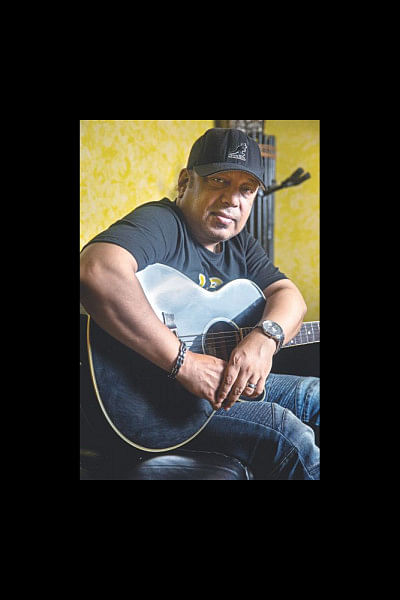

Memories with the Legend

The first time I had met Ayub Bachchu was years ago at a recording in a studio called Art of Noise in Shegun Bagicha. The studio belonged to yet another music legend Foad Nasser Babu from the band Feedback. The studio was a popular amongst rock and pop musicians back in the day and finding Ayub Bachchu there hanging out with his old-time friend Babu was a treat for many of the younger singers and musicians waiting their turn to record. I remember being in a dilemma of sorts, because I had an early morning midterm exam at North South University where I was studying and it was already around 12:30 am. The recording simply had to be completed as well. Somehow Ayub Bacchu got to know about this (it was one of his recordings for a reality TV show) and he found me sitting in one corner of the big studio balcony, pouring over my notes, studying and waiting for my turn to record. "You are Elita, the one with the exam tomorrow?" he asked. "Yes sir!" I said, getting up. "Maa-re-maa!" he exclaimed, an expression used by chatgayyas to vent out anger or annoyance. In his case, it was frustration because the recording was taking a lot of time and he clearly wanted me and the other younger vocalists to feel comfortable. "Why don't you go home tonight?" he said. "Come back to the studio tomorrow after your exams. I will hold your spot—won't be a problem." And that's exactly what I did.

My friends tell me that I am technologically challenged, which is probably true. But it's fascinating how the brain sometimes performs like an old beat-up computer does. The brain takes you back to the first piece of memory ever produced with the legend after it goes through the initial shock of loss and helplessness. And as you process the fact that Ayub Bachchu is actually gone for good, a pool of images stored within the many folders all rush in—one memory overlapping the other, eventually putting your body on standstill mode, unable to function or think. The news of Ayub Bachchu's death seems to have done the same to most Bangalis, in Bangladesh and abroad. While many choose to mourn quietly, most are sharing old pictures, videos or remakes of his famous numbers, paying tributes to the great maestro online.

Bachchu bhai on the other hand, was an enthusiast when it came to technology. He would be all gleeful like a child upon discovering new gadgets and technology. One day when I arrived at his practice pad and studio, AB's Kitchen, located in the popularly termed Kazi Office er Goli, near the Ramna police station, I found a bunch of young people fussing over two brand new cell phone sets—bringing in cables, connecting them to desktops and laptops and so much more. "Elli!" he exclaimed as I stared, clearly overwhelmed with all that was happening. "Check out my new sets! Once I am done transferring my contacts and information, you can hold one and see if you want one for yourself. I will get you a good price for sure!"

Clearly, Ayub Bachchu loved to perform on stage. Not only was he passionate about singing and playing the guitar for his fans at shows, he also loved to talk and carry on addas at his studio with visitors, sharing anecdotes for hours on end. In 2012 after he suffered his first cardiac arrest, Bachchu bhai consciously tried to bring about some lifestyle changes, only so he could carry on with his live performances. Not only did he compromise on many of the food items that he was passionate about, he also tried to sleep at decent hours, trying to give his body the rest it needed. Instead of kacchi biriyani and parata rolls his studio was now filled with fresh fruits, delicious vegetable dishes and healthier options for snacks. Around this time, I would make frequent trips to AB's Kitchen, for a number of shows that I was supposed to sing with Ayub Bachchu and LRB. During breaks or after practice, Bachchu bhai had made a rule of sorts for everyone to have jambura seasoned with a little chili powder and salt, instead of the pakodas and the greasy snacks we would otherwise have. "Elli buchchish!" he would exclaim. "You need Vitamin C and lots of water in your body. This will help you sing and perform better." Clearly, he was repeating what his doctors would tell him, but who could argue?

Ayub Bachchu was an obhimani person. Like all artistes, he wanted his creations to be appreciated and respected. However, he was also very possessive—about his identity, his country, his songs, band, his studio and the people he loved and sacrificed for. He would work hard to produce better than his rivals, but would always acknowledge the good work done by them as well. According to the media and many of his fans, Ayub Bachchu's biggest rival has always been James, yet another living legend in Bangladesh. Stories would float around about how both musicians were always trying to outdo each other, would hardly ever talk to each other even at shows and public gatherings.

Despite all that, two nights ago, at a show which was broadcast live on television, James started off his performance by paying a tribute to the great Ayub Bachchu. "I wanted to cancel the show tonight," he said. "But both Bachchu bhai and I would agree that the show must go on." While playing the heartfelt instrumental tribute on his guitar, James let his tears fall freely, while expressing his love for Ayub Bachchu.

Yesterday, as thousands paid their last respect to the legend at the Shahid Minar, even big names like Asaduzzaman Nur, Minister of Cultural Affairs in Bangladesh and also a powerhouse theatre and TV actor, could not stop their tears from flowing.

In the last few months, Ayub Bachchu seemed restless and always lost in thought. "Elli!" I remember him telling me. "No matter what you do, don't leave your day job. It's important if you want to continue with your music. Don't ever make that mistake!" Last year, the national copyright office in Bangladesh went digital and recognised Ayub Bachchu and myself as the first male and female musician and singer respectively to have their profiles recorded online. At the event where both of us were presented with honours at the Prime Minister's Office, I remember Bachchu bhai talking to me about positive changes in the industry. "Do you think this will change anything for musicians in Bangladesh?" I could understand that he was thinking about proper laws to be implemented by the government so that creators would be paid their royalties accordingly.

At an age and stage where he should have been relaxing and enjoying his life, like all musical legends do all over the world, Ayub Bachchu was busy with live shows, sometimes too many for his own good. Besides the fact that he liked doing shows, was it also because, unlike the other countries with proper laws and royalty system, it is difficult in Bangladesh for a musician to survive otherwise.

But that is another story for another day. Meanwhile, thank you Bachchu bhai for being an inspiration for generations, for breaking barriers in the industry, for creating changes in the society, for teaching people how to love and also for uniting Bangladeshis from all walks of life.

Elita Karim is Editor, Arts & Entertainment and Star Youth. Her Twitter handle is: @elitakarim

Comments