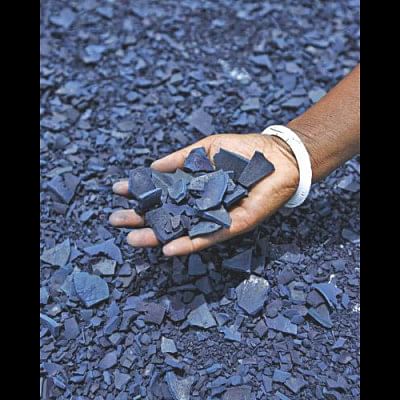

Local indigo goes global

Indigo, which reminds of an episode of cruelty during the British colonial rule, is being farmed once again and the famous blue has recently found its way to the US from Bangladesh.

Last month, one tonne of indigo dye was shipped to the US by Living Blue, a firm co-owned by Care Enterprise Inc and Nijera Cottage and Village Industries.

“This appears to be the largest recorded export of the indigo dye from Bangladesh to the world since the 1860s,” said Mishael Ahmad, manager of Living Blue.

The social business entreprise buys indigo from growers in the northwest district of Rangpur to make dye with the objective to enable growers to generate more income.

“This is a big achievement for us and our farmers. This shipment will enable us to make a breakthrough in the major markets of indigo.”

Marked by resistance of Bengal farmers against the oppressive indigo production system and European indigo planters, who forced farmers to grow indigo for the world market, cultivation of indigo began to disappear from the Bengal since the movement in 1859-62 and became extinct for more than a century, according to Banglapedia.

Its cultivation has been revived in recent decades by some non-governmental organisations to enable farmers to earn more by catering to the global demand for the natural dye.

“Living Blue dedicates the watershed moment to all indigo farmers who were exploited during British India and to the thousands of farmers in Rangpur who cultivate now with pride, dignity and love and this time with a big smile.”

Living Blue, which began its journey 10 years ago to produce indigo and handmade textiles, found a buyer for the natural dye in 2013.

The next year its local sales rose 20 percent to 240 kilogrammes and the social enterprise made its way to the global market for the first time.

Living Blue exported 15 kilogrammes of the item in 2014, according to the company, which has its own atelier in Rangpur.

Shipment halved the following year only to rise to 21 kilogrammes in 2016. The volume of export rose to 35 kilogrammes and the local sale to 271 kilogrammes in 2017, Ahmad said.

Living Blue started with 200 growers and the number of farmers, mostly landless, rose over time. The production of indigo also rose.

As the stock built up, the company kept its indigo production halted in 2017 and 2018. “We were trying to find a big buyer and at last got one,” Ahmad said.

Following the shipment, Living Blue has already started working with growers to cultivate indigo next year.

The social enterprise now works with 3,000 indigo farmers and more than 200 artisans and dyers. It buys indigo leaves from growers to make natural indigo dye and high-end textile.

However, locally made indigo has to compete with indigo producers from other countries.

India and El Salvador are the two biggest producers of natural indigo. There is also presence of cheap chemical indigo and impure indigo mixed with synthetic dyes.

“Many dyers themselves are using adulterated impure dye in the name of natural indigo, either knowingly or unknowingly.”

Living Blue is now considered globally as one of the very few producers of authentic, true Bengal Indigo dye, according to Ahmad.

“Our market is opening and we will have to increase our production capacity in future.”

Ahmad said farmers in the northwest district had been growing indigo even before Living Blue started making indigo dye.

Locals were unaware that this was indigo plants. They gave a different name to it and grew the plant for green manure for crops.

Banglapedia said historical records suggest that indigo was produced in Bengal for use as a dye even in ancient times.

But then it was cultivated more for catering to domestic and ritual needs than to serve as a commercial commodity. Its cultivation for commercial purpose appears to have begun in the 18th century.

Indigo production and its export was a booming business in the early part of the 19th century.

But it fell in the 1840s and as a result profit from indigo production became uneconomic at the peasant level, it said, adding that by the late 19th century farmers preferred to cultivate rice and jute since indigo was no more a profitable crop.

When coerced by planters to cultivate indigo, farmers organised a resistance movement during 1859-60. As a result indigo cultivation gradually disappeared from Bengal.

“Extinct for more than a century, indigo is now being revived in Bangladesh,” Banglapedia said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments