Mission Impossible: House hunting in Dhaka

House hunting in Dhaka is nothing short of a nightmare, and I say this not necessarily because of the disparity of numbers between those who have their own house and who do not. Nor do I have a prescription for bridging the gap that exists between them. Such scientific and statistical calculations are beyond me. I'm just a tenant, and a good one at that! My landlords/ladies love me. Yet, every time I had to go house hunting I dreaded the experience.

Let me start with how it all began. More than anything, I was excited to be moving out of my parents', getting my own place by my own means. I was proud to be a tenant! For the first time the physical accent had shifted onto me. Customers are supposed to be gods. I'm to be pampered and placated when angry. The very thought made me happy.

However, a year of house hunting and numerous encounters with the other species called the land lord have rendered my naivete apart, yielding deeper insights and better understanding about my own position as a tenant in Dhaka's social world.

A pervasive sense of "us" and "them" divides Dhaka society in a manner that goes beyond the black and white division between economic classes. Landlords and their representatives, such as relatives, managers and caretakers form part of this 'us'. In an increasingly land-scarce city if you are an owner of a house, you get to feel a sense of superiority over those who do not. What complicates what could have been just a sense of material accomplishment is the sense of entitlement and power that in turn contributes to the formation of the antithetical relationship between 'us' and'them.'

The 'us' is endowed with super powers—to judge, be privy to any information about my personal life, decide my fate as if they hold me in perpetual mercy by agreeing to lease the house to me for which I am paying. I realised I was now one of that downtrodden, self-effacing social type, the fated 'them' that could only exist at the cost of the 'I' in me.

I am expected to comply with undue demands, let on anything and everything about my personal life, and be ready for unwanted conversations and display of petty power that the 'us' unleash by treating me like a supplicant.

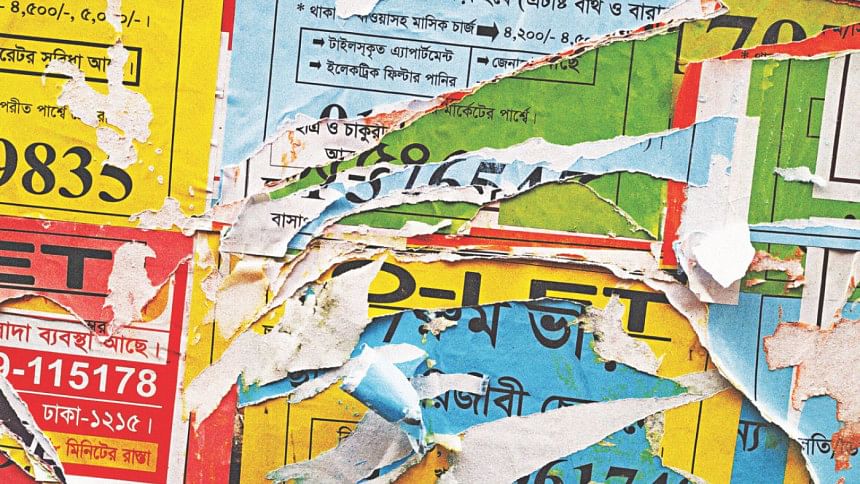

Meanwhile, I am denied free access to basic information about the property. In most cases the gateway to all information remains the landlord's phone number. Some To-Let boards are more generous with indication of the size of the apartment. I remember shortlisting some depending on the size and number of rooms, following up with their owners for viewing, but without much luck. In fact, you can only expect to be lucky in this game of trial and error if you have endless time in your hands. It's like going on a blind date, or the way settle marriage works—you won't even know what you are signing up for. Here are two examples.

Scene I:

I wrapped up office work earlier than usual while there was still daylight; I thought I had planned it right. I spotted an apartment building with more than one To-Let sign on the gate. "The more the merrier," I thought excitedly.

On approaching the guard, I heard what had become too stale a joke for me: "family only." Given my oft-bitter experience as a prospective tenant, I now anticipate all kinds of disastrous encounters. Hence, cool as cucumber, I nodded to assure him.

To my request to view the apartment he looked visibly irritated: "It's too late! The caretaker has left!" I quickly checked my watch—it was around 6 pm—and explained that I could only come after office hours. He eyed my ID card. "Doesn't office break at 5pm? You should have been here straight from office then!" he declared, as if I had been very insensible by investing my time elsewhere.

"It can't happen today! Come tomorrow!" He wrote me off with an authority which he could only enjoy as a member of 'us.' I belonged to the other side of the fence now. Class discrimination was inverted.

As I left with much bitterness, I kept thinking how I, the paying customer, was being treated as if I were at the mercy of the landlord for wanting to rent their place. That's how the dystopic world of 'us' and 'them' works.

Scene II:

This time I was lucky enough to get past the guard. Victorious, I took the lift to the desired floor.

As the lift door opened there he was—the prospective landlord, waiting with his bundle of keys. I stepped out into the lobby, but his eyes remained on the lift until the door closed. As I wondered about the object of his anticipatory look, the man took me by surprise with "Is there no one else with you?" Did you come without a male member accompanying you?"

"It's not a party! Who goes searching for a house with a clan? Women have reached Everest on their own! Has he been hibernating for centuries?" I wondered angrily but kept mum, confirming my solo appearance in his apartment lobby emphatically, almost with a vengeance.

With a loud click the door finally opened onto a sun-drenched, beautiful living room, as if to balance the darkness of its owner's mind. Before I could enter, I saw the same quizzical look in his eyes, this time even graver. "What does he expect of me now?" I wondered.

"Have you given salam?" he asked. Looking at my clueless face, he explained "To the house! You should always enter the house with a salam, or else no angel will visit your place!"

I must have looked absolutely flabbergasted, because he added, "Don't you belong to a Muslim family?" I managed to nod, which made him restate with zeal, "Then it's even more important!"

I was there to rent his house, not his life or values, I felt like reminding him. Drained and frustrated, I motioned towards the door, to which the man looked surprised and almost ordered me to sit. "Why are you in a hurry? We (read: I) need to talk about the details. Thinking it wise not to engage with him, I prayed to God to save me from the verbal diarrhea as he rolled out another salvo of incessant questions:

"Where are you from? What does your husband do? Where do you work? How old is the kid? Which school does he go to? Did you say you live with your mother? Why are you moving out?"

His lack of tact reached a new low when I mentioned that my son was eight. "How old are you?" he blurted out. I told him my age to which the man, squinty-eyed, declared, "You don't look your age." I had gone numb by that time and was glad that I could leave, albeit with a heavy heart, having wasted my day on a futile mission.

"It is not about me. It never was." I had learned. As long as I'm part of 'them,' irrespective of who or what I am like as a person, I cannot win against the psychology inherent in one of the most important yet understudied social relations of Dhaka—that between the landlord and the tenant.

A Dhaka girl through and through, Tabassum Zaman teaches at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB). She is a Dhaka enthusiast, who wants to tell the everyday city anew.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments