The Puzzles of Trees and Moons

Phase One

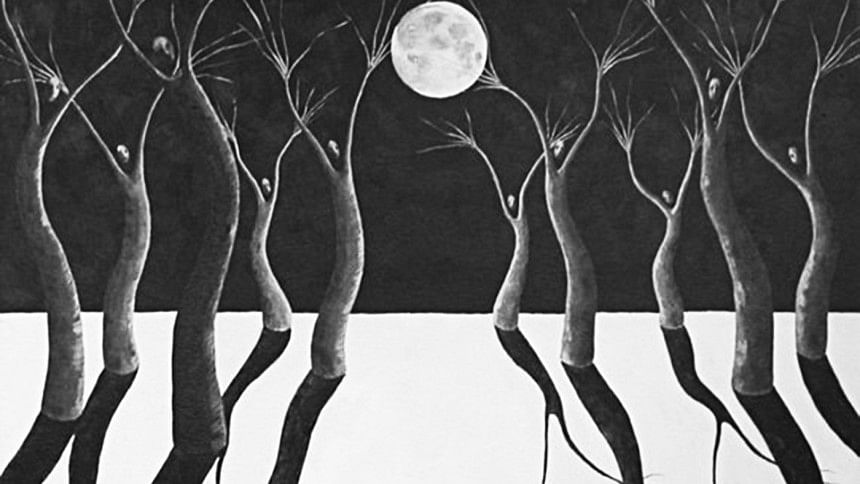

"Everyone has a tree."Golibe said. "And every man craves a moon. The moon is what he wants but the tree is where he ends. The tree is planted when someone is born and is nourished with the energy of the discarded umbilical cord that is buried underneath it. And when a man's journey through life ends, he is buried in the same spot—to reunite with his lost cord. The tree is then cut and left in the open to dry in the sun and rot in the rains."

"But what if the tree dies first? Will the owner of the umbilical cord have to die then?" I wanted to know.

"Trees can die and a new tree can be planted in that spot, but men only die once."

"What about women? Are they immortal in your culture?" I teased.

"Same rule applies," Golibe looked at me and said in a deep voice: "If you were an Igbo woman, nkwu would be your tree too."

"What's an enkuwu?"

"No, it's not the way you say it. Let the n merge with the next sound—like, like 'ng'—clutched between the inner part of your tongue and your uvula."

I gave it a try. Aang, enk, ink, ankh, unkuyu. Since swallowing words is always a hard task for me, I gave up after a few futile attempts. I chided him for wasting my time and demanded to know the real word behind that word. "Just tell me what kind of tree it is, man," I nagged.

"A palm tree."

"Huh! No wonder I couldn't say that word. I'm not a fan of palm trees."

Golibe looked hurt, but what could I say? I really don't like palm trees. I can take an acre of pine trees and happily gather the cruel pinecones and pile them in one corner of my backyard for the hungry birds. I can sit for hours listening to the rustling wind-songs of the pine leaves, or watch the silver raindrops hanging at the tip of every pine needle like melting crystal balls. I can swallow a whole night's sleep watching a lonely moon stuck behind those sharp pine leaves, like one crucified circle of light. But I can never make myself admire the beauty of a palm tree. So I did not understand the depth of Golibe's voice that day when he tried to explain to me the meaning of birth and death for an Igbo man. But then again, I don't understand men who speak in riddles, especially the ones that boast to be poets, and sadly, Golibe was one such man. For some strange reasons, he made it his motto to aggravate me with his puzzling metaphoric language, which always somehow ended in an Igbo sentence—structured in a form of a question and thrown softly at me in a deep yet perplexing manner, which in turn confused me even more. But since it was my inherent nature to let words fly freely, instead of hiding and binding them in metaphors I made it my life's goal not to be puzzled by his metaphors- no matter how alluring they may sound. That way, our friendship stayed safe from all kinds of poetic conundrums.

Phase Two

There were no similarities between the two of us. I was whimsical and hot headed, while Golibe was a wise sage. He always carried his Igbo roots around him, sometimes wearing them as a dashiki, and sometimes, as an agwu, otherwise known as a Kurta and a fedora hat. But I never wore a sari at my work place. If the world that I served was a moon, then I was its dark spot. My brown presence was strong enough to make me visible in the remote Montana university campus where I worked as a technical writer. When Golibe joined as a part-timer, he looked so utterly lost that I had to offer him a friendly hand so that he could find his way.

"I'm Kheya," I said as we shook hands.

"I'm Golibe. Are you Indian? What's the meaning of your name by the way?"

"From Bangladesh, actually. I hope you know where it is; most of the people here don't, and they keep asking me its exact location. I'm tired of playing the role of a cartographer. And oh, the meaning of my name is a small boat, or a dinghy of some sort."

"Of course I know where Bangladesh is. And I like your name."

I was annoyed by his patronizing tone. Why would I care if he liked my name or not? I told him that even though I looked fragile and young for my age, I was stronger than my name.

"Yeah?" Golibe looked amused.

"Yeah." I didn't know what he meant, but decided to echo him, just to make sure that he got my point.

Golibe was a tall, dark Nigerian man in his tumultuous thirties—tumultuous because he was stuck in the middle of a dissertation piece that he had been writing for five years, and because he was secretly in love with a woman whom he described to me as a whimsical cloud that stole his dark moon of a soul the moment he saw her. I had tried a few times to help him with his passionate quest but he refused to involve me as a mediator, saying, "She'll know when she'll know."

I stayed curious about his love interest for a few years but then decided to leave him at peace with his dilemma. Curiosity is a forked road leading to two endings: distraction and obsession, and I had no time to ponder on either of the directions. Once in a while, I would playfully ask him about his mysterious love interest. "Hey there, Golibe-frock! Have you gathered the courage to disturb her universe?"

In response, Golibe would only smile. We usually spent our lunch breaks together listening to each other's stories of failures and hopes. While I ate my lunch and edited his book of poetry, Golibe sat there, like one grumpy man, voicing his frustration about all his deferred dreams. I on the other hand, sat stubborn, like a praying mantis on a blade of grass, too proud to surrender to life's potential miseries. Because I was a technical writer by training, my approach was quite methodical. I penned through his writing and gave him feedback on a timely and logical manner. But because he was a poet, Golibe would always lose track in conversation and talk about things of no relevance to his book. Sometimes he would ramble about trees, or monsoon, or memories of his home; sometimes, he would talk about the woman whom he called his 'mysterious destiny;' and most of the time, he ended up bringing all his fragmented conversations back at me. My olive skin. My dark eyes. My long black hair. The way I laugh. The way I get angry and then burst into laughter the next moment. He would talk about me and about his home in the same sentence and then utter or rather mutter a few Igbo words and sit there, giving me a blank look. I always scolded him, asking him to learn to speak clearly. "Poets are so irritating! You guys can express your thoughts so precisely in your poems. But when you talk, you make no sense!" I used to say. Golibe never refuted me, but he also never tried to explain himself either. And as time passed, I learned to ignore his irrelevant chatter and accepted his inability as a tool of his poetic expression. But that day, when he handed me his completed manuscript, he seemed quite eager to speak sensibly and started talking about his palm tree, the umbilical cord, and his obsession with the various phases of the moon.

Phase Three

"In my culture, the moon is a woman," Golibe said.

"Isn't she so in every culture?" I asked as I kept flipping through the pages of his 'Indigo Moon.'

"I guess so."

"But I don't get it though," I said. "This manly madness for the moon. Moon is nothing but an illusion. It doesn't own the light it displays."

"Yes, moon is an illusion indeed. She shows me what I don't have. Maybe that's why I love her." Golibe then started describing a dance festival, or "the dance of the maidens" as he called it. "In a moonlit night all the women of the village put on their best clothes and adorn themselves with all sorts of ornaments. Under the open sky, in a moon-soaked yard, they surrender their bodies to the rhythm of the beating drums, while a bunch of lovelorn men sit mesmerized, watching and dreaming—with their eyes wide open—of women with whom they want to dancetheir dance of vitality and joy.The moon is a visitor, you know. Like a woman, or like a dream, it visits you and haunts you and leaves you spellbound…"

I was not listening to Golibe's lore of the dancing maidens. My head was stuck in a palm tree. What a unique way to go back to one's root—to the umbilical cord—the starting point of human existence! Golibe was not married and had no family here. Most of his American friends were deeply rooted in the great plains of Montana. There were palm trees in Montana, but his umbilical cord was waiting for him under a palm tree planted by his grandmother in a place called Nsukka by the Niger River. Who would take him back to his tree when he died? I asked him.

"Nwaany onwa," Moon maiden," he said.

"What! O my God, Golibe! You finally had the courage to

approach her?" I could not contain my excitement. "And she already agreed to go to Nsukka with you? You've really impressed me Golibe Nwankwo!" I said. "But first, tell me what you said to her. Tell me everything!"

He smiled his usual calm smile and waited for me to give him a chance to speak.

"… ị ga-abụ ọnwa m?"

"Is that what you told her? What does that mean?"

"Will you be my moon?"

"Awww! How sweet! What did she say?"

Golibe looked straight into my eyes. "She hasn't said anything yet. I'm still waiting for her response." His voice cracked.

"What! Come on, Golibe-frock! Don't tell me you fled the scene before she said anything! You did, didn't you? Now go back, go! Go get your answer!"I pushed him toward the door and went back to my office.

What a cowardly man! I kept thinking as I walked. Poor soul! Only a moon-struck poet like him would be content with an unanswered question.

Fayeza Hasanat is an author and a translator. She writes regularly for The Daily Star Literature Page.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments