Understanding Mughal Dhaka

Unlike Mughal Emperor Akbar's planned capital at Fatehpur Sikri in Agra or Shah Jahan's capital in Delhi—both constructed with a unitary concept over a relatively short time span—Mughal-era provincial capitals like Dhaka (or Lahore) grew piecemeal, during an extended period of time. Little archaeological and textual evidence exists to suggest that any kind of holistic urban system influenced Mughal Dhaka's growth. Instead, the city's building blocks expanded slowly along the Buriganga River and northward, by needs-based spatial accretions within localised configurations.

As for the city's architectural growth, Dhaka never received the kind of imperial patronage that was lavished on North Indian capitals like Delhi, Agra, and Lahore. The European travellers visiting Bengal during the Mughal heyday painted a modest picture of Mughal Dhaka. Niccolao Manucci (1639–1717), Venetian writer and traveller, who worked in the Mughal court in various capacities, described Dhaka in his anecdotal Storia do Mogor, although the veracity of many his claims has been questioned. Visiting Dhaka in 1663, the year Shaista Khan had assumed the vice royalty of Bengal, Manucci described Dhaka as "neither strong nor large, but had many inhabitants; most of its houses were made of straw." During his visit to Dhaka in 1666, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605–1689) observed that Dhaka was predominantly characterized by a linear urban morphology along the Buriganga River, as city-dwellers built houses in the hygienic waterfront area.

A better understanding of Mughal Dhaka's urban and architectural footprints requires insights into the Mughal attitude toward the city, located more or less at the geographic heart of the Bengal delta. This attitude influenced the ways that Mughal Dhaka began. As eminent historian of medieval Bengal Abdul Karim (1928–2007) described, Dhaka developed from a modest settlement to a provincial Mughal capital in 1608 or 1610 (the exact year remains contested) and enjoyed the capital status under the Mughals for the next 100 years. The decision to shift the capital of Bengal from Rajmahal (in northeastern India and on the western bank of the Ganges) to Dhaka is generally credited to Islam Khan Chishti, the Mughal Subahdar or Governor of Bengal, who was a member of the Fatehpur Sikri Sufi family and a grandson of Emperor Akbar's chief spiritual guide, Shaikh Salim Chishti. Located on the northern bank of the Buriganga River, Dhaka's connectivity to surrounding districts through waterways convinced the Mughal bureaucracy to envision the city as an outpost at the empire's south–eastern frontier.

Two key factors contributed to Dhaka's growth during the Mughal era. First, the city's superior geo-strategic location enabled both the surveillance of lower Bengal, which had been ravaged by the Maghs and Portuguese pirates, and the suppression of rebel chiefs. And, second, Dhaka's geography also provided an administrative advantage in collecting imperial revenues and protecting revenue interests. According to Karim, "no official estimate of the population during the Mughal period exists today." However, when Portuguese monk Sebastian Manrique travelled to Dhaka in 1640, he estimated that the population of an expanded Dhaka was about 200,000.

Yet, despite Dhaka's military and commercial advantages, the Delhi-Agra-based Mughal emperors considered ruling Bengal a challenging undertaking, an issue related to their perception of Bengal. In addition to the long distance from North India, Bengal's humid climate—combined with its unique geography, crisscrossed by countless rivulets, its marshy swamps, and its prolonged monsoon season—allegedly gave rise to an ambivalent Mughal attitude toward the Bengal delta as a land of insurmountable remoteness. In the Mughal imagination, Bengal, also called Bhati, was some kind of "Wild East," away from the seat of imperial power. The Mughal view of Dhaka as both a useful frontier outpost and a distant and climatically challenged place perhaps explains why the city does not have a robust Mughal architectural footprint. There are no Taj Mahals, grand mosques, or Shalimar Gardens.

Thus, visitors interested in Dhaka's Mughal architecture will gain a historically nuanced understanding only if they learn how the Mughal powerbase in North India conceptually framed Bengal.

Despite Dhaka's modest Mughal heritage, visitors would be surprised to see a dynamic range of the empire's contribution to the city: mosques, mausoleums, minarets and i'dgahs, forts and katras, palaces and hammams (bathing chambers), Qadamrasuls and Imambaras, and bridges. The key Mughal elements that were introduced to the local architectural scene were dominant central domes, lofty axial entrances set in a central projecting bay (for emphasis), and axial plan. The Mughals replaced Bengal's traditional terra-cotta art with plaster panels. Canonical historiographies of the deltaic region's architecture focus on how Mughal edifices in Bengal were based mostly on the Mughal art and architectural traditions that had developed in North India. However, what has not been researched adequately is the other direction of aesthetic influence. Nazimuddin Ahmed stated that "such unmistakable Bengali elements as the curved eaves and ridge" were diffused "to such places as Lahore, Delhi, Agra, and even as far as distant Rajputana."

The Mughal structures that are located in and around Dhaka might be modest in scale, architectural scope, or artistic excellence, but they offer great insights into the cultural politics of the Mughal Empire's southeastern frontier.

LALBAGH FORT

Standing within Lalbagh one readily recalls the great palace-garden complexes at Lahore, Delhi, and Agra and realizes that this could only have been conceived and built by outsiders to Bengal. No element of the complex is indigenous to the delta.

Richard Eaton, 1996

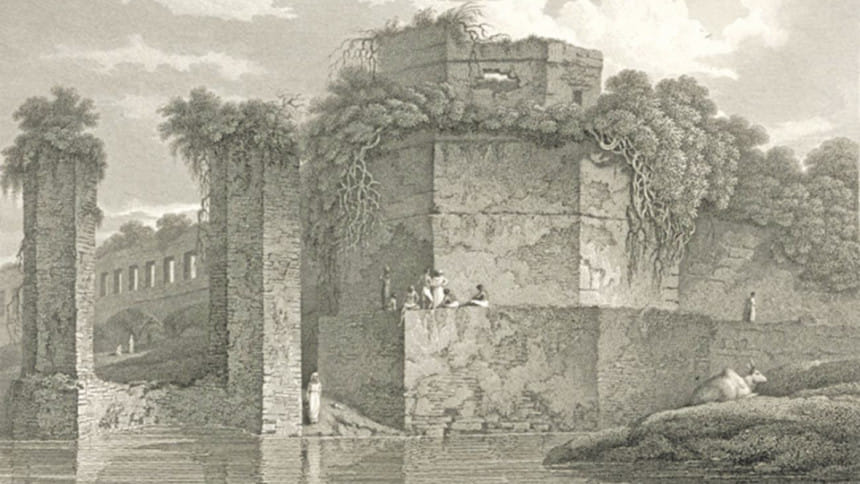

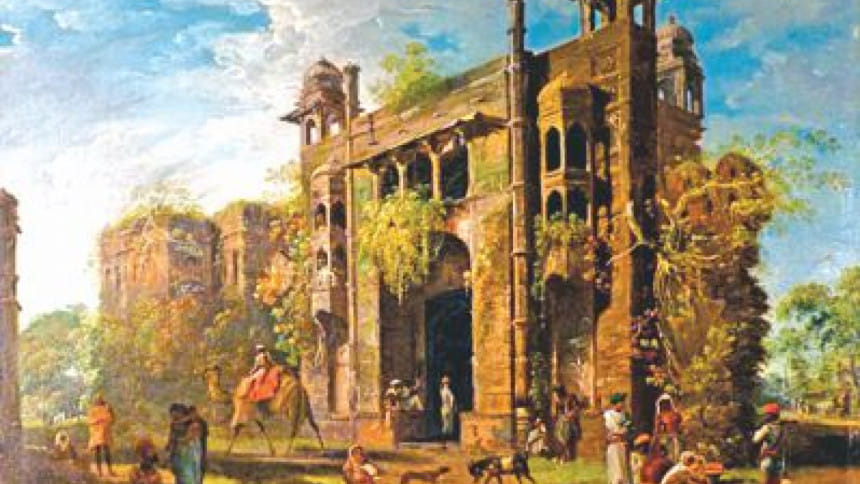

The best example of Mughal building art in Dhaka is the incomplete palace complex of Lalbagh Fort. Undertaken 25 years after the Taj Mahal was built, Lalbagh Fort is constructed on approximately 18 acres of land in the south-western part of Old Dhaka. The fort was originally called Killa Aurangabad (Auragnabad Fort), named after the Mughal Emperor Aurangajeb by his third son and the fort's patron Prince Muhammad Azam (1653–1707). British Collector of Dhaka Charles D'Oyly's sketch titled "Bastion of the Lal Bagh, Dacca" (made between 1808 and 1817) offers an impression that the fort once stood on the bank of the Buriganga River, which has now shifted to the south. The name Lalbagh suggests that it was once a garden of Mughal origin, as in Mughal parlance bagh or bagicha means garden. Historian Ahmad Hasan Dani (1920–2009) mentioned that "the name Lalbagh is difficult to explain, except on assumption that there was a garden on this spot before the fort came into existence." Today, the fort complex, surrounded by a 20-foot-tall defensive wall with semi-octagonal bastions, feels like an oasis in the midst of a bustling old city—its narrow, winding streets filled with shops, vendors, pedestrians, and vehicles of all types. The Archaeology Department of the Government of Bangladesh restored Lalbagh Fort, and it is a major tourist attraction.

Prince Azam initiated the construction of Lalbagh Fort in 1678, during his 15-month-long vice royalty of Bengal, but abandoned the project when Emperor Aurongajeb summoned him to Delhi. His successor, Shaista Khan, continued the construction work. However, in 1684, Khan's daughter Iran-Dukht, also known as Bibi Pari, died unexpectedly. He suspended work on the complex, believing that her death was an omen. Some observers think that the purpose of the fort was to provide safe accommodation to Subahdars during their stay in Bengal. To some, it is a miniature version of the grand palace fortresses built by the Mughals in their capitals in North India.

Upon entry, the visitor finds an axial, symmetrical, and geometrical layout of a lush green garden. The oblong site, measuring approximately 1,082 feet by 700 feet along the east-west axis, includes three grand gateways: two in the north and one in the south. There are three main edifices on the central axis: from east to west, Diwan-I-Khas (the Audience Hall) and the Hammam (bathing chamber); Bibi Pari's tomb; and the three-domed mosque. A large pond is also on this axis, the east of the Audience Hall. Recent archaeology has unearthed remains of more than 25 structures, including those for water supply and sewerage, roof gardens, a water reservoir, and fountains. Together, they reveal the advanced hydrological engineering system that serviced the fort complex.

During the colonial era, the British undertook extensive construction activities inside Lalbagh Fort—including additions and alterations to existing edifices—without any regard to the original design. The Department of Archaeology has removed all of the buildings constructed by the British administration.

Diwan-i-Khas and Hammam

The Audience Hall is a two-story multipurpose structure that served as the Mughal Governor's residence, and housed a meeting hall or the Audience Hall, and the Bathing Chamber (Hammam). The Audience Hall, measuring 26 feet 7 inches by 18 feet 3 inches and containing a sunken ornamental fountain, is approached by a three-bay arched entrance on the east. It is flanked by two square chambers along the north-south axis, containing staircases that lead to the upper floor. The ground-floor plan is repeated on the upper floor to accommodate residential quarters. On the exterior, the ground floor wall presents an elaborate system of recessed niches, and the upper floor has arched windows covered by jali (stone screens).

An imposing arched doorway on the interior western wall of the Audience Hall leads to the central Bathing Chamber through a half dome. The chamber's original domical roof had an opening admitting light and allowing ventilation. Colourful glazed tiles embellish the floor. This chamber demonstrates an elaborate system of hydraulic engineering, recalling the history of Roman baths. To the north, steps lead to a masonry tank, which probably contained temperate waters for bathing. A series of adjacent rooms housed a system for heating water, a private chamber, and a toilet with dressing room—all equipped with covered drains. There was also provision for discharging wastewater into a large masonry vaulted drain, west of the entire complex.

The Audience Hall is a striking case of hybrid architecture. The curvilinear do-chala (two sloping sides) roof over the central hall is reminiscent of the archetypal Bengal hut's gabled roof and drooping eaves, an architectural synthesis that had already appeared in Mughal buildings in the north, such as Red Fort, in Delhi, and Fatehpur Sikri, in Agra.

Tomb of Bibi Pari

Bibi Pari's tomb is based on the characteristic Mughal square plan for mausoleums, featuring a central domed chamber. Examples include the Humayun's tomb (1570) in Delhi and the Taj Mahal (1653) in Agra. With 66-foot-long symmetrical sides, the tomb is located on a raised platform at the centre of a square garden, as in earlier Mughal edifices. A false central dome, sheathed in copper and topped by a finial, crowns the building. Four octagonal turrets, capped by plastered kiosks with ribbed cupolas, hold the building mass of the tomb. The siting of the impressive building reflects the established tradition of the Mughal charbagh (four gardens) planning principle.

The symmetrical interior is divided into nine chambers, including the central chamber, which measures 19 feet on each side. Veneered in white marble, this chamber includes a stepped cenotaph at the centre, embellished with floral motifs in relief and marked as a female grave by a takhti motif on top. The interior walls of the tomb chamber and the ceilings of the other eight rooms are clad in imported white marble and black basalt, respectively.

EPILOGUE

Dhaka's decline began when Murshid Kuli Khan came to Bengal as diwan and transferred the capital from Dhaka to Murshidabad in the early 18th century. Around this time, the city that slowly began to assert its geo-strategic position in Bengal was Kolkata, founded in 1698 by the English East India Company when it was permitted to return to Bengal from Madras.

Scholarly research and interpretive histories on Mughal Dhaka from the vantage point of physical planning are scant. While Abdul Karim's Dacca, The Mughal Capital has been viewed as a crucial contribution to the literature on Mughal Dhaka, its analysis of Dhaka's urban growth is somewhat limited in scope. Wayne Wilcox, a Columbia University professor, reviewing Karim's book in the wake of its publication in 1964, wrote rather wryly: "The author seems more at ease in fixing the date of Dacca's choice as a Mughal headquarters than in weighing the roles of the various groups involved in the economy. At his best in describing the muslin industry, he avoids many of the interesting and unexplored ecological problems of a frontier Muslim city, founded in the interest of imperial defence, sustained as a market and manufacturing city, and manifesting an urban persistence to the 20th century as the reborn capital of eastern Indian Islam." It is time to see the next generation of critical historians, who would explore histories of Dhaka, from the ancient period to the 20th century, with new insights and from a global perspective.

Adnan Zillur Morshed, PhD, is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist, and teaches at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. He serves as executive director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at BRAC University. He is the author of DAC/Dhaka in 25 Buildings (2017). He can be reached at [email protected].

Comments