Some ways to reduce youth unemployment

In a recent podcast interview, renowned particle physicist Brian Cox said that the scientific community was generally of the consensus that the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the recent breakthroughs in automation technology are likely to replace millions of workers around the world, primarily in jobs that do not require a high degree of skill. He said that scientists believe that the coming shift would also create new jobs, but it is difficult to foresee what kinds of jobs those will be this early. What they are certain about, according to Cox, is that human beings are still superior to machines when it comes to their ability to think, be creative and to innovate, which are the most vital faculties that push human civilisation forward.

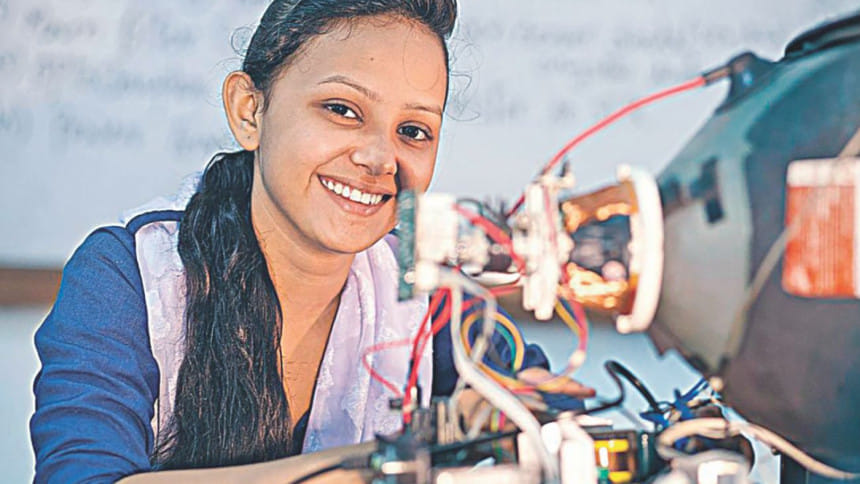

Coupled with the fact that the jobs of the future will largely be tech-based or at least tech-driven, the role that the youth of today will have to play in the development of any nation must be well understood and appreciated. After all, they are the ones who, having grown up in the 21st century's tech-driven environment, are best suited to adopt the most cutting-edge technologies that now exist, especially as these technologies are constantly being updated and improved upon at a speed never seen before. In this setting, the fact that the employment condition of the youth population in Bangladesh looks grim should seriously concern us as a nation.

According to the Asia-Pacific Employment and Social Outlook Report 2018 published by the International Labour Organization (ILO), the youth unemployment rate in Bangladesh went up from 6.32 percent in the year 2000 to 12.8 percent in 2018. That is a doubling of the rate over a span of only 18 years—a period when the youth population has increased by a big margin—which means that the total number of unemployed youth in our country has actually risen much more than what seems on the surface.

If we consider the official statistics of last year just to compare, we see that the overall unemployment rate was estimated to be only 4.2 percent, while the youth unemployment rate was estimated to be 10.6 percent—with one in every 10 young people being unemployed. That is, the majority of those who were unemployed were young people, which, from a traditional market viewpoint, is not a very common occurrence, particularly during times of great technological shifts.

What is even more surprising is that according to the Labour Force Survey 2016-17, unemployment among the youth who had received secondary level education was as high as 29.8 percent, while it was 13.4 percent among those who had received tertiary level education. This means that unemployment in our country is actually higher among the more educated sections of young people compared to those that are less educated. This trend also seems to be on the up, as in fiscal 2016-17, the rate of unemployment among individuals who received education up to the tertiary level went up by 9 percent from a year earlier, according to data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

What explains these strange contradictions? And does it not suggest that the education that is being provided at our higher educational institutions is, to some extent, an important contributing factor to these oddities? After all, according to the previously mentioned ILO report, Bangladesh has the second highest graduate level unemployment rate in the entire Asia-Pacific region only behind Pakistan. And, according to a World Economic Forum report released last year, Bangladesh once again lagged behind other South Asian nations at leveraging Information and Communication Technology (ICT), coming in at 125th position in the ICT Skills Index—behind India at 102, Nepal at 117 and way behind Sri Lanka at 30.

When seen together, these two reports suggest that our higher education institutions are indeed failing to provide students with skills that are considered to be important, especially when it comes to the technological knowhow that is needed for the employment of the future, as explained by experts from various fields of expertise. While this is one area that we certainly have to focus on to improve, what we also cannot forget is that some of the most important global innovators didn't necessarily discover their world-changing inventions from what they had learned at their higher educational institutions. Rather, many of them had, in fact, opted out of their respective educational institutions to pursue their dreams of becoming inventors and entrepreneurs.

In order for our youth to have the courage, motivation and determination to pursue similar paths, the culture of how we view potential innovators and inventors, and those looking to become entrepreneurs and even those trying to establish their own start-ups, must change. As without the support of their families and from society at large, it is extremely difficult for young people to pursue the bold path of discovering something new and important, which could eventually have a cascading net positive effect on society, including on the road to generating new employment opportunities.

Another mentionable point in regards to education is that, while it is important to introduce new technologies in the curricula at educational institutions, we must remember to be extremely cautious not to abandon the irreplaceable attributes that the great teachers of history have always possessed. That is, the ability to motivate students, to inspire them to be curious and to pursue their curiosities, to think for themselves and to develop the moral character and principles that would serve them throughout their entire lives. If teachers can ingrain such values in their students, then the youth of today, with the innumerable tools that they have available at their fingertips (e.g. the Internet), should be more than capable of succeeding in high-tech fields even without much direct assistance. And, in fact, that is how it worked in most cases in countries that have had the greatest success in developing the most advanced and innovative technologies that we see in our world today.

This is where providing more and more centralised government-planned education may not be the best option, as it almost always concentrates on maintaining the status-quo, rather than nurturing out-of-the-box thinking among students, that challenges them to look at things differently. However, at the end of the day, rethinking our education alone may not be sufficient.

If we want to encourage the young citizens of our country to become the great inventors and entrepreneurs of tomorrow, then we must also support them through easier access to financing and better government policies.

Given the way our financial sector has been performing, it can be said broadly that it has made the possibility of financing new businesses extremely difficult for young people. When banks grapple with non-performing loans (NPLs) in ways that our financial institutions are at this moment, they become reluctant to finance new business ventures even when those ventures show great promise to succeed. This form of “overheating” in the financial/loan market may contribute quite substantially in preventing new businesses from setting up and flourishing, by making it difficult for potential entrepreneurs to get access to financing through the traditional banking channels. This should provide another reason for the government to fix the numerous problems that are plaguing our financial sector—and have been for a very long time. Through improved regulatory oversight and strict adherence to banking policies, the government could ensure that businesses that have the capability of becoming big employment generators in future, are able to establish themselves with the help of the necessary financial assistance from banks.

But even if it manages to increase the contribution of banks in financing new businesses, the amount of funds that can be made available to young people may not be optimised through that alone. To optimise resource allocation, the government therefore could also partner up with the private sector and encourage established corporations to work and perhaps even invest a part of their R&D budgets in the innovative ideas of start-ups and new businesses if they see some benefit in it.

Along a different path, one major aspect of focus for the government should be to reduce corruption and red-tape. Young people who are among the most intelligent and conscientious (the best two predictors of business success according to behavioural research) are naturally reluctant to start a business in Bangladesh, fearing corruption and other related problems such as having to pay bribes. And their reluctance to resort to unfair means is completely justified; merit-wise, they have what it takes to succeed in just about any other country in the world where corruption is not as high as it is in ours.

As a result, many of these brilliant young individuals tend to go abroad to either start their own business, or to work for some of the biggest and most reputed companies in the world. While some may think that's a good thing as it reduces competition in our domestic job market, that is actually the wrong way of looking at it. As we are seeing increasingly around the world, it is new ideas and inventions that are now the central generators of employment, as automation continues to rapidly replace humans in performing more rudimentary jobs. Therefore, what we are actually losing are highly qualified people whose creative abilities could generate many more jobs than are being left for others to grab in their absence.

And even besides that, those who are choosing to get employed at established companies in Bangladesh, simply because of the overwhelming red-tape and other troubles of setting up a business (even though they would prefer to), are also potential employers that we are losing out on. This is where the government must act to reduce the hidden costs of doing business in Bangladesh that disincentivise new businesses to set up shop here. The government needs to realise that at the end of the day, businesses tend to thrive where there is more freedom and less bureaucracy. It is with this in mind that the government should adjust its existing policies, as well as formulate new ones.

Although these steps along with others can help young people become self-employed and owners of their own businesses, not everyone is tuned nor aspires to become an entrepreneur. Which is why, government policies must be set up considering how to benefit these people also.

What is odd about unemployment being higher among the more educated sections of our youth is that a large percentage of the top echelons of managerial positions in different industries of our country are being held by foreign workers. Aside from reducing the scope of employment for Bangladeshis, what this also does is cause large outflows of money from our domestic economy in the form of remittances.

There is, however, nothing wrong with businesses looking to hire the most qualified employees they can find. What we should concern ourselves with is trying to find out why those who are being considered as the most qualified for top managerial positions are not Bangladeshis. That is, what capabilities are lacking in our workers, and what can be done to change it.

As is well known, Bangladesh is currently enjoying what is recognised as a period of “demographic dividend”. Unfortunately, we haven't really been “enjoying” it as much as we've been scratching our heads, trying to figure out what approach to pursue to make the most of this demographic dividend.

Yet, the truth of the matter is that there is no one “best” approach. And to get the best outcome, what is needed is the application of different measures that, when combined together, can connect and create net positive outcomes when it comes to generating more job opportunities, especially for our young people. Be that through encouraging young people to start their own businesses, or by providing them with greater skills as per the demands of the labour market.

What is obvious is that whoever fails to adapt quickly to the demands of our changing times will eventually get left behind. Thus it is up to us and our policymakers to make the choice of not falling into that category by being proactive, rather than reactive, in our actions, and to try and make the most of the opportunities that are coming our way, during the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. His Twitter handle is: @EreshOmarJamal.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments