My memory from a time in the past

My copy of this book is almost 25 years old. I looked for it in my shelf, not because I wanted to revisit those "good old days", nor because I wanted to recapture memories of my mother reading it to her daughters.

Maybe curiosity was reason enough for my wanting to go back to those pages. I was keen to figure out why I still remember those verses of Nolok or Jhaler Pitha and why the book had such an impact on me. With so much attention on his other poetry collections like Sonali Kabin and Kaler Kolosh, I feel his children literature somehow fell through the cracks.

I decided to reread this book, one that has been tucked away in a corner, and has not received the attention it deserves, through the eyes of my adult self.

And it was indeed a mini celebration.

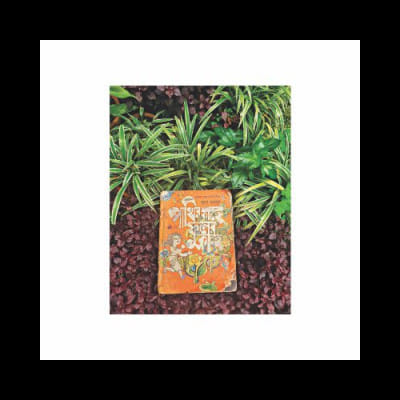

The copy that I have is a first edition, published in 1980 by Bangladesh Shishu Academy. Back then, it cost Tk 6. Yes, you read it right—16 poems with full page illustrations at Tk 6. The book was a hand-me-down from my sister, and long before we could learn to read it, my mother used to read it to us. Now, looking back, considering how sophisticated the language was, and how complex some of the poems' content, I feel the book was meant for slightly older children. Nonetheless, the musicality of Mahmud's words would keep us hooked, without us getting lost in the plot.

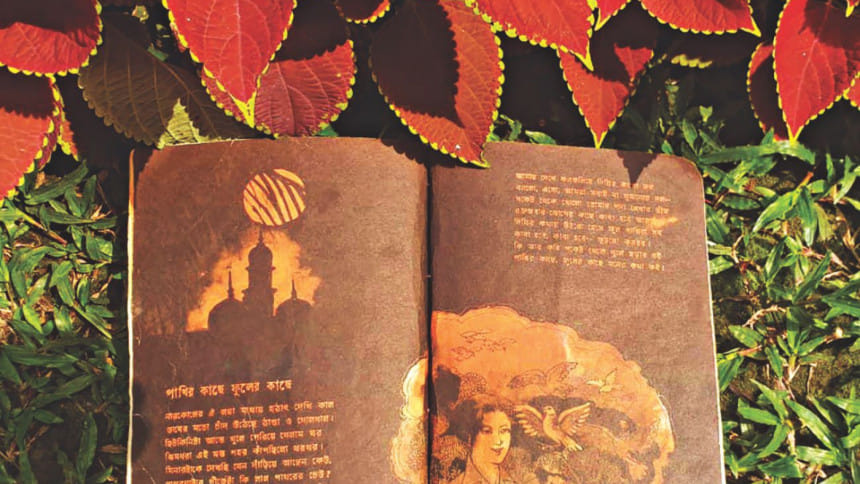

With themes like nature and history, social justice and identity, love and imagination, this book displays Al Mahmud's mastery: the ability to convey a complex message in a language that is pleasing to young ears. Of all the poems, Pakhir moto (Like a bird)—a poem about someone who keeps on daydreaming while her parents force her to concentrate on her studies—was my mantra to live by. Back in those days, when we kids were repeatedly reminded that our flights of imagination wouldn't take us anywhere, his words made my periodic trips to la-la land, a justified affair. Instead of frowning upon children for spacing out, Al Mahmud encouraged the little minds to take off to their own world!

If you are already an admirer of Al Mahmud's poetic narration of rural landscapes, this book will confirm what you already know. With Al Mahmud, I learnt to talk to birds and trees, rivers and mountains. I was perhaps ridiculed for being absent minded, but the seven-year-old me had the courage of my convictions, and funnily enough, these poems were to blame for fostering in me the faith that it was okay to allow my head to float in the clouds.

In this book, Mahmud also looked at national moments from our history—the language movement of 1952 and mass upsurge of 1969—and communicated those big ideas to young readers, using simple, accessible words. Long before we studied these movements in our textbooks, Al Mahmud's sloganish phrases in the poem, Unoshotturer Chhora:1—Truck truck truck/ Shuyormukho truck ashbe/Duyor bedhe rakh!—would fire up our young minds and pique our curiosity. They sparked conversation in our home, with our parents and with each other. We would ponder: what is a curfew? Who is Asad? Who is Motiur? Which side should we be on? Who won, who lost? These poems made us realise that history matters, allowing and encouraging us to identify with our history, politics and culture.

A strong sense of justice pervades Al Mahmud's poems. While in Boshekh (the first Bengali month of summer), he is furious that people who are already less fortunate pay with their lives when the storm comes, in another poem, with no title, he expresses the plight of hundreds of people who lost everything because of the construction of the Kaptai Dam.

In Hashir Baksho, Monpoboner Nao, or Jhaler Pitha, Al Mahmud does not just mention class and inequality—he encourages children to learn and respect social justice and diversity. He does so, without reservations that children might be unable to grasp the complexity of such issues. Through these poems he taught his young readers that not all children had the same privileges in life. His poems are an attempt to foster compassion in children, in small daily doses.

Beside the poetry, what sets this book apart, for me, is the beautifully crafted illustrations by Artist Hashem Khan. A doodle-y imperfect font with just the right amount of ornamentation on the bright orange cover made it one of my absolute favourites.

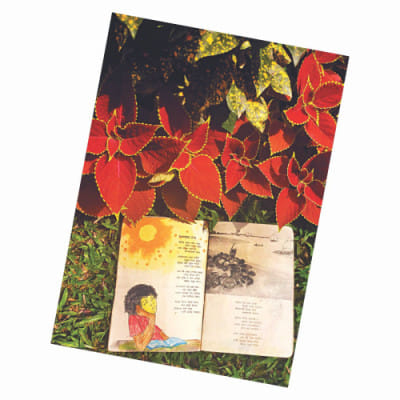

As I flipped through the book, along with Hashem Khan's enchanting, stylised full-page line drawings and water colours, I discovered how I, too, unleashed my creative potential to the fullest. I found the Piccasso in little me using the poetry book more like a colour book, filling Hashem Khan's outlines with crayons and making my own customised edition.

Al Mahmud's poetry and Hashem Khan's illustration balance each other, without taking anything away, allowing for the magic to be felt and read—loud and clear. What's particularly special about this book is that it boldly slips strong messages into children's literature and provides plenty of conversation starters for a child and her parents. I would still like to call him one of my childhood favourites—for all of these beautiful memories that he gave me through this book, and also for all those magical adventures he took me on.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments