For whom the bell tolled

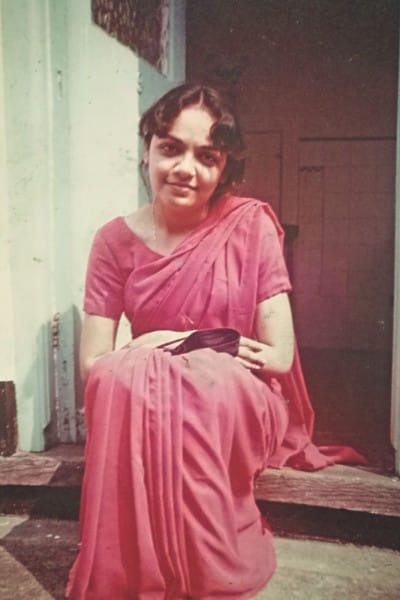

Simeen Mahmud was an accomplished researcher working on issues of women's empowerment, women's work and labour force participation, and gender norms in Bangladesh. A statistician and demographer by training, Simeen was educated at the University of Dhaka and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She was also a MacArthur Fellow at the Harvard Centre for Population and Development Studies.

Starting her career at the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) in 1974, Simeen eventually rose to become research director. She soon came to focus her life's work on gender-focused development as an interdisciplinary researcher. She was co-founder and coordinator of the Centre for Gender and Social Transformation at the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development at BRAC University. She was part of the global collaborative research projects, Citizenship DRC and Pathways of Women's Empowerment.

Her articles appear in The Lancet, Population Studies (of the London School of Economics), Feminist Economics and the Oxford Development Studies Journal of International Development, among other journals. Simeen has also written numerous book chapters in publications by Oxford University Press and Routledge, among others.

She was affiliated with numerous research and development institutes around the world, including the Institute for Development Studies (IDS) at the University of Sussex, the Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre, and the Global Development Institute at the University of Manchester. Simeen was also chairperson of the board of trustees at Central Women's University.

Naila Kabeer, longstanding colleague and friend of Simeen Mahmud, pays tribute.

Simeen Mahmud died on April 19, 2018. We are now coming up to the first anniversary of her death and it is still hard to believe that she has gone. I have wanted many times to write about her and each time I try, it seems to end up being a lot about me. Our lives were intertwined in so many ways that perhaps it is inevitable. That is the reason for the quote from John Donne's poem in the title of this piece. The day that Simeen died, the bell tolled for her but also for all the rest of us whose lives she touched in so many ways.

Simeen was a friend, a colleague and a moral compass for me for much of my adult life. When someone like that dies, the empty space she leaves behind is not just her physical absence but all the possibilities that will now never be realised, the discussions we will never have, the papers we will never write, the jokes we will never laugh at together, the meals we will never share. I will never be able to pick up the phone to ask her about her views on some problem that is troubling me.

In one sense, Simeen and I go back a long way, really all our lives. Our families moved in the same social orbit, my mother and her mother were great friends. But our childhood trajectories diverged. I went to school in India and came away soon after to study, work and live in the UK. She spent much of her life in Bangladesh apart from her degree in the UK. Our paths crossed only intermittently.

They began to cross more regularly when I came to Bangladesh in 1979-80 to do fieldwork for my PhD and attached myself to the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies where Simeen was a Research Fellow. She had a background in demography and I was studying fertility behaviour so our research interests overlapped considerably. But it was only when I began coming back to Bangladesh on a more regular basis as part of my research activities at the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex that our professional trajectories began to converge and our personal relationship solidified into a friendship that lasted till the day she died.

From 1999 onwards, we have collaborated almost continuously on a series of major research projects, along with the team of young scholars that she led, first at BIDS and then later at BIGD. The projects covered child labour, civil society and citizenship, Bangladeshi garment workers in global value chains, economic pathways to women's empowerment, gender dynamics in labour markets and most recently, the impact of the Accord and Alliance initiatives on working conditions in Bangladesh garment factories. While the concern with gender in relation to health, fertility and women's reproductive role remained a continuous thread in Simeen's research trajectory, what brought us together professionally was our shared interest in the working lives of women in Bangladesh.

In a country in which women have been defined primarily in terms of their reproductive roles while dependent on men for their daily sustenance, Simeen had a long-standing commitment to rethinking definitions of economic activity so as to more accurately represent women's significant productive contributions. One of her earliest reports (1989) was a review of women's role in agriculture. It attempted to go beyond the official definitions of economic activity to capture the kinds of economic activities women in rural areas were routinely engaged in.

As might be expected, the report found much higher levels of economic activity for women than suggested by conventional estimates. Looking back, however, there were two other conclusions from that study that are worth recalling. The first conclusion challenged the dominant image of farming households in Bangladesh which saw it as made up of a unified production system under male headship. In reality, as the report pointed out, men and women had different sub-systems of production, characterised by different degrees of autonomy and different degrees of interdependence. The second conclusion recommended that development interventions move away from offering poorer women the stereotypical income-generating activities (handicrafts, sewing) that prevailed at the time and offer them opportunities for more profitable forms of self-employment, such as livestock and poultry rearing.

These findings, made nearly 25 years ago, remain topical. Our most recent research together confirms what has taken scholars in Bangladesh a considerable amount of time to acknowledge—that women in rural Bangladesh do indeed have their own spheres of economic activity within or around their households and that they exercise considerable degree of control in relation to them. In addition, our research tells us that, thanks to microfinance and asset transfers, many poorer women have gained access to livestock and poultry rearing, the activity the report had recommended, and that it has been associated with their movement out of poverty.

A more recent attempt (2008) by Simeen and BIGD colleagues to measure women's work in the eight districts covered by our survey was able to distinguish precisely the kinds of work that Bangladesh's official labour force surveys were failing to capture. These were the home-based market-oriented activities carried out by women, mainly livestock and poultry-rearing, and various expenditure/cost-saving forms of work. Both should be counted: the former belong within conventional ILO definition of labour force activity while the latter belong within its extended definition. Official estimates suggested that only 30 percent of women in Bangladesh were economically active. Our estimates suggested that it was closer to 70 percent. In other words, women in Bangladesh are critical to their livelihoods of their families, in spite of all the social restrictions on their economic activities. What the paper made clear is that how you ask questions about women's work and who you address your questions to will determine the accuracy of the answers you get. Official efforts continue to ask these questions to male household heads and to couch them in ways that are guaranteed to perpetuate the myth of Bangladeshi women as the eternal dependents of men.

Simeen and I shared an interest in processes of transformative change in the lives of poor people, and of working women in particular. Here we worked in parallel sometimes, in collaboration other times. She explored the impact of microfinance on women's empowerment in an article conversationally entitled 'Actually, how empowering is microcredit?' Unlike a number of contributions in this rather polarised field, where researchers set out to prove one predetermined answer to this question or other, Simeen did what her title suggested: she set out to 'actually' find the answer. Her conclusion was positive, but highly qualified: microcredit did not do much to expand women's material resource base, the loans in question were too small, but they did promote their agency in decision-making processes. She came up with a similarly qualified conclusion in another paper on the same topic, co-authored with colleagues from demography: access to microcredit did not promote women's mobility in the public domain but it did strengthen their role in household decision-making and certain dimensions of self-esteem. Such results meant that she neither dismissed the empowerment potential of loans nor did she believe it could be taken for granted.

In a jointly authored paper, Simeen and I explored the impact of different kinds of development NGOs on how poorer men and women fared as rights-bearing citizens. We decided to compare three categories of NGOs: those narrowly focused on microcredit; those that combined microcredit and social development; and those that opted for savings-led approaches to social mobilisation. The results were striking: development NGOs narrowly focused on microcredit were less likely to report political impacts than the rest but, less expectedly, also less likely to report economic impacts! Members of organisations that focused on social mobilisation were not only more likely to report political activity in terms of voting, campaigning and collective action but at least one also reported higher levels of economic activity. Pursuing this theme further, Simeen was able to show women who belonged to the social mobilisation organisations made for far more active and effective members of the Health Committees that had been set up by the government to monitor health services in rural areas. It appeared that the processes associated with social mobilisation helped the rural poor to become active citizens.

A third area in which our interests converged was in relation to women workers in the export garment industry. We shared the belief that, while wages and working conditions in the industry left a great deal to be desired, it offered jobs that were a considerable improvement on the casual forms of wage labour, the only other option for women with very little education. One of our earlier studies supported this point—it showed that wages, working conditions and social benefits were higher for garment workers, particularly in the export-processing zone but outside it as well, than for other forms of waged work for women in urban areas. Our later study demonstrated how women workers in garment factories were at the receiving end of efforts by both global buyers and their Bangladeshi suppliers to keep relationships informal so that they could pass on the risks to those lower down in the value chain—with workers bearing the costs of this strategy. While we found scattered evidence of protest and collective mobilisation by workers, Simeen wrote an article to explain why this protest was not more widespread: workers with few other options cannot afford to mobilise for their rights. Our last collaboration was also on this topic. We were investigating the impacts of the Accord and Alliance agreements which were put into place to improve health and safety after the Rana Plaza disaster. She was working on analysing the data when she died.

For all of us who worked with her professionally, what stood out about Simeen was that she was free of some of the less attractive characteristics of many academics. She did not have that inflated ego so common among academics of her stature that is in constant need of boosting! On the contrary, she loved her work, got joy out of it, enjoyed the collaborative nature of it and remained optimistic about the future of the country. She was generous with her time and knowledge; she nurtured her younger colleagues and invoked fierce love and loyalty in return; she was intellectually curious but also empathetically engaged. She worried about the lives of the men and women in her research and sought to communicate her concerns through her research and advocacy. Given her focus on working women, she was often struck by the hypocrisy of a society that looked down on poorer women who were forced to do hard physical labour in fields, roads and people's homes, believing them to lack 'honour', but gave status and respect to educated women from wealthier households who could work in the relative comfort of their homes, offices and schools.

As a friend, she was tolerant of differences and disagreements, willing to listen and argue, to persuade and be persuaded, she was serious about life but also readily amused, happy to be teased, generous in her praise, cautious in her criticism, extremely kind but willing to tell people off very firmly if she thought they deserved it. She and her husband turned their home into a hospitable space where we could gather frequently for good food and intelligent gossip, an unbeatable combination.

And I saw her as a moral compass because of the integrity she brought to all aspects of her life. In her professional life, she hated shoddy work, she hated people who took short cuts or made grand statements on the basis of very little evidence. She took care that whatever work she produced was as rigorous and solidly based on evidence as she could make it. In all matters, she was someone whose moral instincts you could trust, to whom you could express reservations and concerns and know that you would get a fair hearing and whose judgement on difficult issues were always clearly thought through. She was a devout Muslim who practised her faith without ostentation, quietly, modestly and generously. Through her practice rather than any declaration on her part, she was a constant reminder to those who knew her that compassion and mercy are central tenets of Islam.

Naila Kabeer is Professor of Gender and Development at the Department of Gender Studies and Department of International Development at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Her research interests include gender, poverty, social exclusion, labour markets and livelihoods, social protection and citizenship and much of her research is focused on South and South East Asia. Naila is currently involved in ERSC-DIFD Funded Research Projects on Gender and Labour Market dynamics in Bangladesh and India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments