Lawrence Ferlinghetti Hits a Century

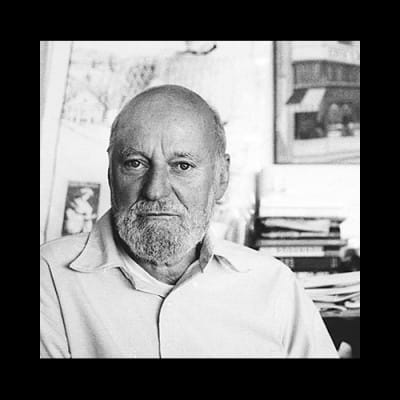

Thanks to Google I have, at a click of the mouse, discovered that in our time around 165 members of the literary professions have lived to be a hundred or more. Of them, sadly, only 15 are poets; and of these 15 only three are familiar names: the great Chilean poet Nicanor Parra, and two contemporary Americans, Richard Eberhart and Stanley Kunitz. Another American is set to join their ranks. Poetry lovers worldwide are waiting to toast Lawrence Ferlinghetti on his 100th birthday, which falls on 24 March.

Elaborate programmes have been drawn up to celebrate the event. The main venue, naturally, is City Lights, a Ferlinghetti brainchild, named after a celebrated Chaplin film; like its "sister store," Sylvia Beach's historic Shakespeare & Co., it is both bookstore and publishing house, and one of the most celebrated literary landmarks in the world today. As a sort of run-up, on the 21st it hosted the launch of Ferlinghetti's new autobiographical novel, Little Boy. A host of writers including Joyce Carol Oates and Maxine Hong Kingston read from the work at the party.

Come the big day – tomorrow, that is – City Lights will remain open from one to five p.m. for a marathon birthday bash. Anyone who feels like dropping in to read from Ferlinghetti's works or to listen to others read is welcome. There are parallel events elsewhere in San Francisco and New York. A month-long exhibition of Ferlinghetti's art work is on show, and there will be shows of a documentary on his life and work. The reader can find details of the entire range of centenary events at the City Lights website.

My aim in this little piece is not to report on the celebrations but to add a modest personal tribute to the international chorus of praise. My interest in Ferlinghetti is not scholarly; indeed I am acquainted with only a small fraction of his many volumes of poetry and prose; but over the years it has given me immense pleasure and exerted a palpable influence on my own poetry.

My knowledge of Ferlinghetti's life too is far from comprehensive, but even a brief sketch will impress one with his varied background, achievements and interests. He was born in Yonkers, New York, the posthumous son of an Italian-American father. His mother, of mixed French and Portuguese-Sephardic extraction, was committed to a mental asylum soon after, and he was taken by his mother's aunt to Paris, so that his first language came to be French. The two returned to New York five years later, and after finishing high school he took a first degree in journalism from the University of North Carolina. World War II was then in full swing; he became a naval officer, took part in the Normandy landing, and served later in the Pacific. The devastation of Nagasaki, that he saw at first hand, turned him into a Pacifist.

Demobbed as a Lieutenant Commander, Ferlinghetti took an MA from Columbia University with a dissertation on the influence of John Ruskin on J. M. W. Turner, and in 1949 received a doctorate from the Sorbonne for a thesis in French on the urban aspect of modern poetry. He then married and settled down in San Francisco, teaching briefly at the University of San Francisco before taking up a full-time literary career. Setting up City Lights with a friend he showed remarkable entrepreneurial acumen, launching the highly successful Pocket Poets Series that published Ginsberg's Howl (1956), for which he had to fight an obscenity charge in court. An anarchist in politics, Ferlinghetti has also had a colourful record of activism: anti-Vietnam War, pro-Sandinista, Castro-friendly, anti-nuclear, pro-farm workers.

Like many of my generation in the subcontinent I owe my first encounter with Ferlinghetti to Penguin Modern Poets Volume 5, which also featured Ginsberg and Gregory Corso. What an exciting fare in such a slim paperback! I read and reread the poems, chanted them, intoned them, even sang them.

The three poets are also quite varied, differing from each other quite markedly, though all are labeled "Beat." Like all labels it has its limitations. It overlaps with the San Francisco Renaissance and "wide open poetry," a tag derived from Neruda that Ferlinghetti likes. The latter even declared once that he didn't write Beat poetry. I suspect he wanted to distance himself from the vatic side of someone like Ginsberg.

Since that first heady encounter I have read Ferlinghetti's poetic masterpiece, the best-selling (over a million copies gone) A Coney Island of the Mind (1958), the translations from Jacques Prevert's Paroles (1958), and the exciting mix of prose and free verse in Poetry as Insurgent Art (1975) and Writing Across the Landscape: Travel Journals (2015).

I see an intimate connection between Prevert and Ferlinghetti, in their valorization of accessibility, in their casual rhythms and diction, their bitter humour. Reading Ferlinghetti's translations of Paroles and his own poetry side by side it's easy at times to mistake one for the other, though the American is clearly the zanier of the two. I think Francis Ford Coppola is spot on in his characterization of Ferlinghetti's poetry: "Lawrence gets you laughing and then hits you with the truth."

This mix of humour and seriousness pervades Ferlinghetti's oeuvre. But If I have to choose a single poem above all the others it has to be "Underwear":

I didn't get much sleep last night

thinking about underwear

Have you ever stopped to consider

underwear in the abstract

The insomnia and the philosophic undertones of the phrase "in the abstract" hint at deep-seated problems. These problems are universal:

Underwear is something

we all have to deal with

The Pope wears underwear I hope

The Governor of Louisiana

wears underwear

I saw him on TV

He must have had tight underwear

He squirmed a lot

Here we have a politician in a tight spot during question hour on TV: one of the small pleasures of life in a democracy. The distinction between public and private spheres breaks down in the modern world:

Women's underwear holds things up

Men's underwear holds things down

Underwear is one thing

men and women have in common

Underwear is all we have between us

You have seen the three-colour pictures

with crotches encircled

to show the areas of extra strength

and three-way stretch

promising full freedom of action

Don't be deceived

It's all based on the two-party system

which doesn't allow much freedom of choice

Could there be a more entertaining yet telling indictment of consumerist capitalism and bourgeois democracy? Humour is perhaps the best weapon for philosophic anarchists. Looking back I can sincerely avow that "Underwear" was the inspiration behind my poem "Ode on the Lungi." And so, tomorrow I will sit in a lungi and toast the laureate of underwear.

Kaiser Haq is a poet, translator, essayist, critic, academic and a freedom fighter. Currently, he is the Dean of Arts & Humanities at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments