The 1971 we don’t talk about

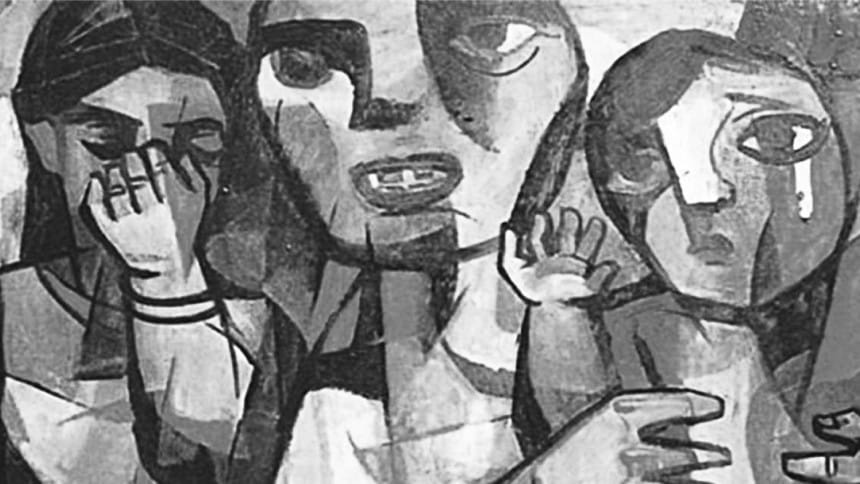

According to estimations, around 200,000-400,000 women were tortured and raped by the Pakistani Military and their collaborators during the Liberation War of Bangladesh. The numbers could be even higher. No one knows. In a country where patriarchal norms are still revered, many think that talking about the War heroines (Birangonas), or even being one, is shameful.Many think that their roles were not as significant as the freedom fighters.

Imagine living inside a bunker impenetrable by sunlight, crammed with 20-30 others, naked, or only with a little piece of cloth stuck to your body, sweating profusely in the hot season, shivering with the same intensity during winter when there's not enough cover. Imagine not knowing what day and what month it is. It's been so long. You haven't witnessed generosity. Imagine a day lasting like a year, with no privacy of one's own, the hellish tortures repeating frequently, as though they have become a ritual. For the captive women in 1971, life was very similar.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman clearly had something else in mind as he, with respect and honour, titled the violated women "Birangona." The motive behind the naming had been simply to ignite a successful effort to recognize them as normal human beings who had actively taken part in the war as well, although differently. Despite the effort having a potential to heal and cure the wounds, the dehumanizing societal norms didn't spare the Birangonas since they were women and as the norms dictated—impure. The people who worshipped those norms refused to give the Birangonas the dignity they deserved, negating the notion put forward by the nation's father. Those people were the same ones who breathed the independent air and walked the independent soil. The independent air and soil that came at the cost of the Birangonas' sufferings.

As if their (the Birangonas') infernal trials in the concentration camps weren't enough, they had many other battles to tend to post independence. Battles that rendered the achievement of independence (for them) petty. Battles that they had to engage in just for being the victims.

One of the narratives of the seven interviewees for the book, Ami Birangona Bolchi, could be easily found online, whose narrator is T. Nielsen (formerly known as Tara Banerjee), a Birangona. When I read the translated excerpt in The Daily Star, I was satisfied with how her destiny had unfurled. At the same time, I was unhappy because not every story had ended similarly. The many Birangonas away from Dr Nilima Ibrahim's book are now struggling to make their ends meet. Some are on the streets, some are earning less, as opposed to what they deserve. They could be any of the women who emerge with the traffic lights of Bangladesh's cosmopolitan areas, having skin wrinkled by age, treading through the vacant spaces of the carnival of stationary cars, begging for money. They could be any of the grey haired women nestled between the legs of an over-bridge in Farmgate and Mogbazar, staring glassily at the independent city people pacing forward with their independent city lives. Although Dr Nilima Ibrahim's book portrays chronicles that are tremendously cruel and inhumane, the compilation doesn't represent the degree of sufferings and their aftermaths every Birangona had to face. It's just a first person view into the lives of those the author could screen. In the face of history's death and silence from many violated women's ends, the fact that she could seize the seven stories and provide the readers a clear glimpse, is admirable.

The narratives are testaments to the fact that for a violated woman, her family wasn't her best friend. Although some were taken in by their families whole-heartedly, some weren't. There is one such example where the husband refers to his wife (a Birangona) as a "witch" on her return, in front of their son. Besides, there's one Hindu minor who doesn't contact her family after independence because her family wouldn't want her, given she had been violated at the hands of "Muslim" men. Such accounts are visible in most of the cases.

In the book, we see how one of the interviewees makes remarks about not having a single street throughout the country named as a tribute to their sacrifice while many portions of the country are thick with streets named after the male fighters and trailblazers. We see how women are not given saris to wear and forbidden to keep long hair in the military camps because they could commit suicide by tying themselves up inside. We see how inhumane and predatory the military is—the animalistic rapes, the scant respite from the ritual.

We see how the Pagri of one Indian soldier unspools to cover an undressed Birangona, the long, hot showers at the Dhanmondi Rehabilitation centre feels so calming after enduring a lengthy period of brutality, the first morsel of lovingly cooked lunch tastes with family. How satisfying acceptance is. How depressing estrangement is.

Dr Nilima Ibrahim deserves an ode for her work. Not only because of the compilation, but also for the journey that she had to undertake for setting these stories free, beyond the victims' lips. Like managing successful adoptions (mostly encouraged by willing Canadian citizens), and triumphantly convincing many fleeing Birangonas (Pakistan bound) to stay since leaving would bring more uncertainty into their lives, the journey rendered her a godsend for the distressed women.

"Ami Birangona Bolchi" is an important document that shows that glory is not about selective admiration. It is a sanctuary for some war heroines' stories. It is a little something that gives one the nudge to see how women are so vulnerable in war zones; their battles being of many kinds. It is an invisible hand that opens the Liberation war shaped window and invites the readers to look into its female victims and their various shades of distress. As inhabitants of an independent Bangladesh, we need to know about the war heroines, flaunt their contributions proudly, and do our best so that their history doesn't die or get manipulated by time.

In the past few years there have been talks and efforts to rehabilitate the Birangonas. We have seen photos of old women living in shanties or in abject poverty. We have been assured through a few instances that show monetary help or a brick-built house for a Birangona. But have they been accepted by the society in general? I wonder if Bangladesh's education curriculum will ever add stories like the ones here to the higher secondary Bangla books and bring the young learners closer to history and humanity. When will we be able to accept that rape is not a matter of shame or guilt for the woman or her family, but that it is a heinous act and a punishable crime committed by the perpetrators?

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a regular contributor to the Star Literature Page.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments