Mapping genocide in Khulna

War leaves its traces everywhere, be it in the form of memories or mass graves.

Yet, even after 49 years of the Liberation War, many such traces remain unexplored, or at best, partially explored.

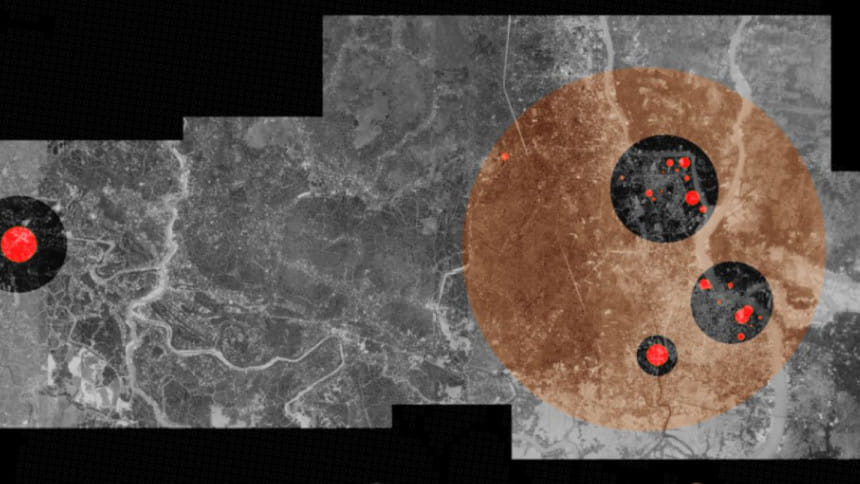

Documentary photojournalist Turjoy Chowdhury started to photograph the killing fields, mass graves and torture cells of Khulna to create a visual map based on the accounts of eyewitnesses and survivors of the 1971 genocide.

“Unfortunately, the generation that was supposed to work on it did not. Our generation is now faced with the problems of lack of documentation and archiving. We are the last generation to be able to meet and record the survivors,” said 27-year-old Turjoy.

The project visually represents the major locations in Khulna where mass killings took place. The photographs revisit and (re)interpret the atrocities that occurred in certain sites by photographing them in their current state, drawing a conceptual link between the past and the present.

“Historians have written books about these sites. I started as a photographer, and I wanted to explore how to connect the present and the past timelines through visual representation,” said Turjoy. He called it a “creative research project”.

The photojournalist visited the spots where atrocities were carried out by the Pakistani army, photographed their current states and interviewed survivors. The aim was this -- history must not be lost in the annals of amnesia.

He selected Khulna for documentation, because it is his birthplace, but also because of the district's role in the war.

“The very first Razakar camp and concentration centre was set up in Khulna. The Chuknagar massacre which took place on May 20, 1971 is said to be one of the worst mass killings during the war. In addition, one of the largest killing fields in the country, Gollamari, is also in Khulna,” said Turjoy.

The documentarian describes the surreal feeling of visiting the sites.

“I went to Forest Ghat first,” said Turjoy, referring to a jetty on the Bhairab river where people were killed every single day. Historians say that the dead were thrown into the river from this jetty.

“After 49 years there was no trace of anything. I visited in the afternoon when the local people go to Forest Ghat to take walks, hang out and eat jhalmuri. When I tried to reimagine what the jetty was like in 1971, it was such a big contrast to what it is now,” he said.

The locals knew nothing about the genocide that took place on the jetty, he added.

And this amnesia, this not-knowing is what the project is hoping to counter in the future.

“This is a part of a bigger project and I hope to cover the rest of Bangladesh too,” stated Turjoy.

To see the interactive project online, scan this QR code on your phone or visit http://campaign. thedailystar.net/genocide/

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments