The real Lalon

Only a year later, in 1890, Shaiji would breathe his last at the age of around 117.

The literary and musical prowess of baul Lalon Shah outshine many of his contemporaries, and several generation of musicians and writers have drawn inspiration from him, from Rabindranath Tagore and Nazrul, to Allen Ginsberg, not to mention countless bauls and other Bengali authors. Yet, unfortunate as it may seem, very little is known about the man himself. The shroud that covered the life of the mystic exists still.

While there is no documentation that Rabindranath Tagore actually met Lalon, bauls believe that the two did meet. However, it is known that bauls made visits to Shilaidaha where Tagore had a kuthibari. Many of his songs are influenced by baul traditions, and some bauls were in turn influenced by Tagore.

Perhaps, Tagore’s acquaintance with the mystic singers of greater Nadia was made through his elder brother, Jyotirindranath Tagore. Twelve years older than Rabindranath, Jyotirindranath had a great influence in shaping the mind and thoughts of his impressionable younger brother, who eventually went to achieve greatness that surpassed all his siblings.

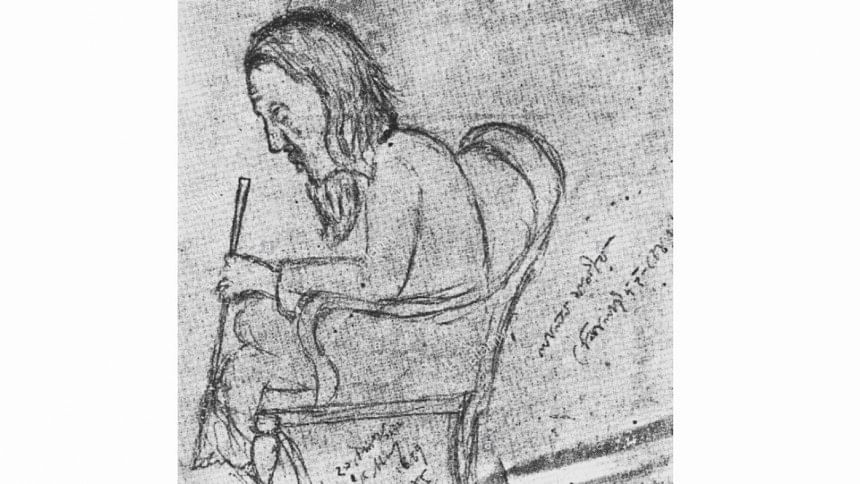

Jyotirindranath Tagore was a playwright, an accomplished musician, translator, and prolific in drawing. Of the near 2000 sketches that are now preserved in the archives of Rabindra Bharati University museum most are of the ordinary people he met in his day to day life.

It is not clear how Jyotirindranath met Lalon Shah, but his sketch of the great mystic remains the only authentic image of the bard.

There are claims that his face bore scars of small pox; and that he lost his vision in one eye — none can say for sure. Once we treat Jyotirindranath Tagore’s sketch as the only evidence, it reveals that Lalon, unlike the striking baul depicted in most images, was a man with a somewhat roundish face, long hair, and a flowing goatee!

The mist surrounding the mystic gets thicker as one delves into other aspects of his life. Lalon disdainfully rejected all sorts of labelling, apart from being a human being perhaps.

Lalon spoke little of his early life, and much of what we now consider to be true is simple conjecture.

Lalon Shah was a phenomenon, even in his lifetime. The cult following only got bigger and wider spread after his death. While his philosophy was rejected by orthodox practitioners of almost all religions in the subcontinent, his later followers muddled his secular views by imposing their own religious dogma on what they presented as the work of Lalon.

The controversy does not stop there.

Lalon received no formal education and it is widely regarded that among his disciples only a few could write. It was through the efforts of Rabindranath Tagore that in late 19th century, about 298 songs were collected, and till this day these remain the most authentic documentation of the lifetime’s work of Lalon. Yet, when compared to the figure of 2000 that bauls believe is the conservative figure of Lalon’s songs, it becomes clear that a lot remains to be unearthed. Much of what exists does through oral traditions, and for decades, researchers have debated over their authenticity.

Myriad interpretations of Lalon’s philosophy have been proposed, and it is of little surprise that “interpretations,” too, vary considerably. It is important to note that as Lalon’s philosophy is available to us only through the verses he composed, authentic rendition of his songs are necessary.

In recent times, another highly debated aspect has been the tunes of his verses. Experts have attempted to classify them in three distinct variants — one belonging to the bauls themselves, — a distinct style that is often called the “Akhrai” tradition; the second group of artists are the “old-school” exponents of Lalon who adhere to a blending of the Akhrai tradition and classical music. And the last is the “fusion” by pop artists.

As the Akhrai tradition is strictly oral, one handed down from one baul to another, the tunes vary from singer to singer. This varies from that of the urban Lalon singers who try to blend classical music with Lalon songs for a more polished presentation. And fusion music is of course, in a class of its own.

The several levels of controversy that surrounds his life, work and the way he shaped music and our literary thought will be ever present, but to project the “real Lalon,” what is needed is more collaboration among researchers, and greater respect for each other among all who love to call themselves a student of everything that was, and is, Lalon.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments